When I was 26 years old, I moved to Southern California and almost immediately took a job as a waitress in a beautiful Indian restaurant. Of my many waitressing jobs, this one would have the shortest life. I had forgotten one of the most important waitress caveats: Never take a job in a restaurant merely because you like the kind of food served there or have preconceptions about the culture from which the cuisine originates. Unfortunately, I made this rookie mistake about 10 years into my waitressing career when, clearly, I should have known better.

One reason for my hasty and ill-considered decision was that I grew up in a family with an affinity for all things Indian. My parents lit incense and listened to Indian ragas. My mother wore a lot of Indian clothing and provided me, when I was little, with a series of Indian comic books detailing the legends of Krishna and Shiva. Later, there were plenty of books on Indian philosophies lying around the house for me to read.

My parents also were great believers in karma. When I was in my teens, my entire family became vegetarian -- a virtually unheard-of phenomenon in 1970s New York. For my parents, and for me, India was appealing on many levels. There was the exoticism, the elusive scent of enlightenment and, of course, the food. Curries, chapati and, especially, Indian tea ranked very high in my house, although they always seemed hard to find and cooking them properly posed some problems. Without the proper ingredients and recipes, Indian cooking was merely guesswork. We were, therefore, always searching for a good Indian restaurant in which to dine.

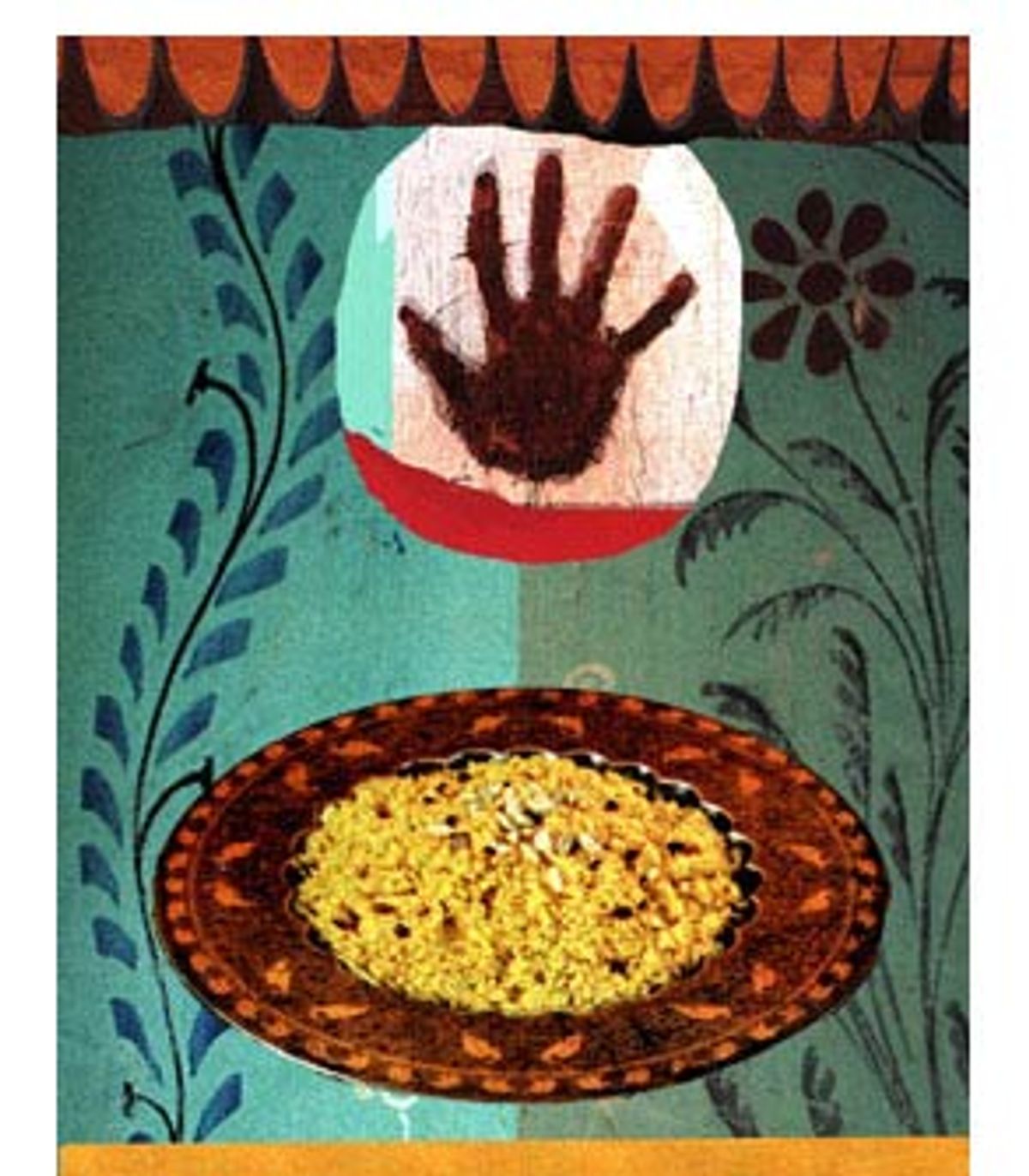

Thus, when I was offered the chance to work in an Indian restaurant, I leapt. What luck, I thought, as I surveyed the restaurant's dark interior. There was an elephant head over the bar, keeping watch over the inventory of Indian beers. The kitchen had an authentic tandoor oven and, in the dining room, there was bamboo as far as the eye could see. Instead of the usual swinging doors leading from dining room to kitchen, there were several thick strands of brightly colored beads separating the rooms. The scents of saffron, cardamom and turmeric permeated the air. I was in heaven -- until my first shift.

Within a couple of days of starting my new job, I had a long list of reasons to leave it as soon as possible. To begin with, the restaurant was owned and managed by an extremely ill-tempered trio of brothers from northern India. There was a long-standing family dispute between these three that seemed to have its roots in their respective childhoods and threatened, every day, to escalate into a full-fledged feud. Whenever more than one of the brothers were in the restaurant at any given time, they quarreled loudly and incessantly in Hindi. When only one brother was present, he would complain, in English, about one or both of the others.

Ironically, all three brothers had an identical management style, which was to tell the non-Indian staff (which consisted of me, a couple of other waitresses and the kitchen crew) absolutely nothing about how the restaurant was to be run and then complain later that the rules weren't being followed. When directed at the waitresses, these complaints were delivered with cool and haughty disdain. The brothers, it turned out, were on the misogynistic side. They tended to keep a frowning distance between themselves and the waitresses.

The all-male kitchen staff did not receive the same treatment. Every day, there was a shouting match among the brothers, the cooks and the dishwashers. What made these daily altercations most interesting was that the entire kitchen staff was Mexican. The brothers would stand and scream at the cooks in Hindi and the cooks would fire back in lively Spanish. Nobody really had a clue what anybody was going on about most of the time.

(After listening to my complaints about the brothers, my mother weighed in with the opinion that there was an obvious reason for the brothers' splenetic behavior. All three were rabid meat eaters, which was, she claimed, "out of the normal order" for Indians. The ensuing repressed guilt over their meat consumption was no doubt the reason for their querulous natures, she said.)

My second complaint was with the uniform. All the waitresses were required to wear saris. At first, I thought the dress code was both innovative and romantic. When the wife of one brother came in with a selection of saris for me to choose from, I felt like I was shopping in a Bombay bazaar, fingering elegant cottons and silks. And, actually, the sari would have been fine if, in fact, I'd been visiting Bombay or touring the Taj Mahal. Unfortunately, it was more or less impossible for me to serve curry and tandoori chicken in a California restaurant with the sari catching under my feet, trailing into the dishes and falling off my shoulder. And the beaded entrance to the kitchen that I'd thought so charming became an absolute nightmare when I tried to maneuver the sari and the dishes through it, tangling up the food and cloth with the least provocation. It turned out that wrapping a sari was a skill in and of itself, one I clearly did not possess. I looked ridiculous, I thought, and felt extremely uncomfortable.

And then there was the food. I'd envisioned myself eating sumptuously and sampling all my favorite Indian foods. This was not to be. The brothers advocated rather a heavy hand with all manner of cleaning fluids in the kitchen. As a result, most items had a frightening chemical undertaste that more or less ruined the delicate spicing of the dishes and inspired a fear of poisoning. The brothers also were frugal. Let's just say that certain curries and puddings stuck around much longer than they should have.

The sole saving grace was the Indian tea, or chai, which was hot, fragrant and intoxicating. There was always plenty (the brothers drank it heartily) and I imbibed to my heart's content.

In the end, it wasn't the hostility, the sari or the food that really signaled the end of the job. Rather, it was the slowness of business, the annoying customers and, that inevitable death knell of a waitressing job, bad tips.

After a few days on the job, I realized that the restaurant was surrounded by several of the kinds of institutions that have made SoCal famous. There were a few yoga rooms, a transcendental meditation house or two and some other amorphous "centers" that touted enlightenment in a few easy steps. Many of the patrons would convene at the restaurant for lunch, clasping their hands in the Indian style and murmuring "namaste" to each other. They were all, it seemed, on some sort of restrictive, cleansing diet -- one that didn't involve being civil to the waitress. Serving curry in my sari, I was clearly not as evolved as these enlightened practitioners. And, apparently, tipping was not a part of nirvana.

After a month, I found myself not only disillusioned but cash poor, and decided that my passage to India was officially over.

On my last, particularly slow, shift, the youngest brother, "Jim" (he never went by his Indian name), suddenly warmed to me and decided, after I extolled its virtues, to show me how to properly prepare Indian tea. The tea was the one item that the brothers always prepared themselves and it sat, in a giant pot, warming on the stove all day. While I watched, Jim threw handfuls of loose tea, cardamom pods and cloves into boiling water, then measured out milk and sugar from memory. It was easy, he told me. Tea was the easiest thing to make in the world. It required no thought at all.

The next week, I started my next job at a diner serving tuna melts, omelets and cappuccinos to patrons who were avowedly unenlightened and generous with their tips. I couldn't even think about eating Indian food for at least six months.

My illusions of India had been bruised during my brief stint in the restaurant, but not dashed. I had, after all, come away with a wonderful recipe for the tea I consider nothing short of an elixir. The stuff masquerading these days as chai in local coffeehouses doesn't even come close.

When I make it now, I remember Jim telling me that it takes no thought at all and the tea comes out perfectly every time. And, I have to admit, there is a little bit of enlightenment in this act. Just a little.

Shares