My wife, Matt, and I were in a small shop called Ten Thousand Villages -- one of many such shops, staffed by volunteers and sponsored by the Mennonites -- which offers native crafts from around the world. I had ducked in a few days earlier, looking for a present for an elderly friend who's hard to buy for, and found what I hoped would be just the thing, a mobile from El Salvador strung with miniature clay cooking pots.

Matt thought it was a gas -- you just can't look at it without smiling -- and we had rummaged through the entire stock to find the one we liked the most. I was heading for the cash register, mobile dangling from one hand, when I was stopped in my tracks. Here was something I hadn't noticed at all during my last visit -- a little table with platters of bite-size snacks for customers to enjoy while they browsed: chicken satay from Indonesia, spice-coated cashews from India, corn bread from Guatemala and, last, Tibetan curried potatoes.

Now, I am the sort of person who not only has forced fancy grocery stores to put up "One Sample per Customer, Please" signs beside the cheese-tasting plate but has also revealed the signs' total futility. After all, it is nothing to walk around the store (or, if one is in a hurry, around the nearest display case) and return with a fresh expression of pleased surprise: "Catalonian aged goat cheese? How fascinating!"

Here, however, there was no intimidating signage, so I simply took root at the spot and prepared to have a second lunch. As it turns out, however, there are only so many spiced cashews, chunks of chicken satay or (especially) wedges of Guatemalan corn bread you can get down without a free beverage's being provided as well. I was reluctantly deciding enough was enough and preparing to move on when I took a little bite of the Tibetan curried potatoes for politeness' sake. In my personal lexicon, the word "curry" is all but synonymous with "acid indigestion" and, given this association, "curry" plus "potatoes" hardly inflamed my imagination.

To my astonishment, what I tasted was so compellingly good that it took every bit of my self-control to keep me from grabbing the tray and running out of the store, muttering "Mine! Mine! Mine!" Instead, I just remained where I stood, eating as many of the potatoes as I could, while Matt, who was already acting as if she had never met me, moved to the far end of the store.

On reflection, it isn't all that easy to explain what it was about the dish that seized hold of my appetite and wouldn't let go. The potatoes didn't possess what some food writers like to refer to as "big taste" -- that is, a knockout flavor that wraps its fist around the eater's tongue and makes it cry uncle.

On the contrary, they had a sort of innocence of flavor that made them completely at home among the artisanal crafts surrounding them. What these potatoes expressed was not the studied complexity of the master chef but the carefully polished minimalism of peasant cooking, where a few simple ingredients are aligned in perfect proportion to create a radiantly delicious dish.

The potatoes were tender; their coating, redolent of ginger, garlic, pepper and other spices, was neither a dusting nor a sauce but a kind of fragrant, savory integument, the sole purpose of which was to alert the mouth that something totally delectable had just arrived.

The platter emptied, I left the store in a golden haze.

"I have to get the recipe for that dish," I said after a while, when I had calmed down a little and Matt had begun to act as if I might be her spouse.

"Well," she said, "why don't you just go back to the store and ask them for it?"

If you think this is a sensible reply, you are probably a woman. Setting aside the question as to whether I would be allowed back into the shop, for a guy, a suggestion like this is the verbal equivalent of a bucket of cold water. It is the sort of exchange that most often occurs on the highway, when the driver (male) has lost his way and the passenger (female) suggests, in that same reasonable voice, that they stop the first pedestrian they see and ask for directions.

It's not that this is an obviously bad idea. It just misses the point. For men, getting lost isn't a mistake -- it's an opportunity to exercise those basic survival skills hard-wired in their brains. These skills may be rusty and unreliable, but they're there, and once released from the kennel, they don't want to go back inside. They want to run until they drop. And if that means going miles out of the way -- or, more likely, driving around in a big circle, saying all the while, "I know what I'm doing" -- well, that's the way it goes.

Even so, after searching through our cookbook collection, I was beginning to worry that she might be right. Although we are professional food writers and own enough of those tomes to sink the average garbage scow, we didn't have a single book, or even a portion of a single book, on the cooking of Tibet.

There's a simple reason for this: It had never occurred to me in my whole life that I might want one. The only Tibetan recipe I knew was hot buttered tea -- and somehow, until now, that had seemed more than enough. I can't be alone in this feeling, since a thorough search of all likely Internet sites turned up only a single title: "Lhasa Moon Tibetan Cookbook" by Tsering Wangmo and Zara Houshmand, published by Snow Lion, a tiny house in Ithaca, N.Y., that specializes in titles on Tibet and Tibetan Buddhism. (For those who might wish to combine the mystical and the mundane, it offers a special gift pack containing a copy of "The Tibetan Book of the Dead" and a jar of Tibetan Dead hot sauce. The pack sports the catchy slogan "Soul food to die for and the book that will bring you back.")

I went to Amazon.com to check out reader comments on the "Lhasa Moon Tibetan Cookbook" and came across this rave from a reader in Lancaster, Ohio: "I was delighted to find recipes for such things as butter tea, tsampa (parched barley flour), dried cheese and even chang (barley beer)."

Hmm. All of a sudden, my interest in Tibetan curried potatoes started to wane. Doubts besieged me. Was I on a recipe hunt or merely the victim of some twisted karma that came from eating too many highly spiced cashews? After all, what were potatoes doing in Tibet at all? Wasn't this a country that had refused entry to foreigners for centuries? Did the rule not apply to any edible tubers the foreigners might be carrying? This seemed highly unlikely. Was this all some sort of hoax?

I decided to give the effort one last toss of the dice. I went to my current search engine of choice, typed in the three words "Tibetan curried potatoes," and pushed the search button.

Here it became evident that some sort of karma, twisted or otherwise, was guiding my actions, because I forgot to select "exact phrase" for this search -- which would have resulted in no hits and thus ended the whole project. Instead, my search turned up 43 matches, the first of which was a link to an article that appeared in Vegetarian Journal in 1996, called "Trekking in Nepal."

As it happened, the author, Cheyne Keith, a practicing vegetarian, would have starved to death in Nepal if it weren't for potatoes, since Nepalese, like Tibetans, although Buddhist, are out of necessity meat eaters. (Since Buddhists believe that all lives are equal, they prefer to eat larger animals, thus eating more and sinning less. The Dalai Lama has expressed personal dismay at the number of lives lost to produce even a single serving of shrimp -- although this seems an unlikely temptation to come the way of most Tibetans.)

Nepal shares not only a common border with Tibet but much of the same cuisine, and potato dishes there are not an exception but an ever-present rule, as excerpts from Keith's diary reveal. "Lunch included a delicious curried potato-cauliflower dish ... At an inn in Ngadi, we ate several scrumptious plates of tiny golden potatoes fried with garlic and accompanied by a spicy and salty chili relish ... potatoes again for lunch ... In Manang, we ate hash brown potatoes for breakfast." And so on.

Furthermore, Keith, who before taking this pilgrimage was a chef in New York, ends his narrative with several recipes he collected during his time in Nepal, including one for a Nepalese potato curry. It was interesting, but since potato curries -- both "wet" (with sauce) and "dry" (fried plain with seasonings) -- are commonplace throughout the Indian subcontinent, it was not all that helpful. I needed to know what would make such a potato curry "Tibetan." Instead, what finally turned the key in the lock for me was the following passage:

In Pissang a group of British soldiers on a climbing trip introduced us to one of Nepal's most tasty dishes: Potato momos. A momo resembles a Polish pierogi except that momos often came with pebbles or twigs imbedded in them. While always bland, they were served with a spicy and salty chili relish. During the next week, as the altitude steadily increased over 10,000 feet, I began to crave them fried and not boiled. I also began to eat an awful lot of them.

Momos, as popular as they are in Nepal, are the national dish of Tibet. These dumplings -- very much in the same family as Chinese chiao-tzu, or pot-stickers -- have three traditional fillings: meat, vegetable and potato. Tibetan momo recipes aren't at all hard to find on the Internet -- I even came across the purported favorite of the Dalai Lama himself -- and by a careful reading of the nuances in the seasonings of the potato momo fillings, I began to piece together the fabric of a wholly satisfying and authentic-feeling dish of, as I shall now call it, Tibetan dry-fried potato curry.

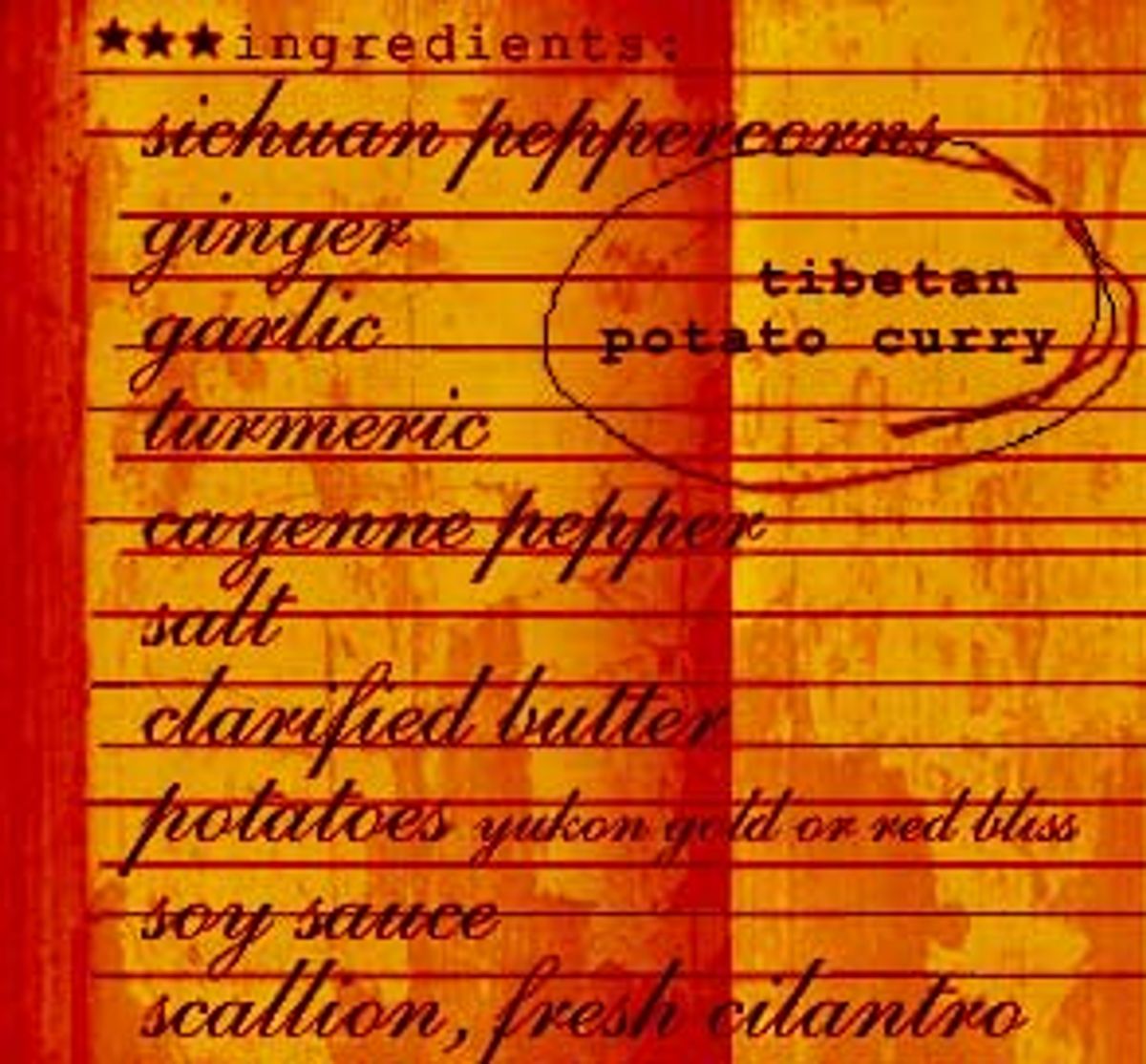

Tibet, although it has stubbornly -- and, to a great extent, necessarily -- held onto its own culinary traditions, has also felt free to help itself to appealing aspects of both Indian and Chinese cooking. Characteristic seasonings that appear again and again in Tibetan dishes include ginger, garlic, soy sauce, turmeric, ground dried or minced fresh chili pepper, emmo (Sichuan peppercorns) and generous amounts of chopped fresh cilantro, which are used to produce dishes with a full rather than overpoweringly pungent taste.

These are the seasonings I used to create my own Tibetan potato curry. Because this combination of flavors doesn't immediately call up a particular cuisine, you'll find that this dish can be served in many different situations, especially because it is as good at room temperature as it is fresh from the skillet. (It's an excellent accompaniment to barbecue.) However, my favorite way of eating it is all by itself as a late-night snack, especially now that prepped and parboiled cubed potatoes are usually available in the supermarket produce section.

Finally, you might want to know how my version compares with the one I sampled at Ten Thousand Villages. I honestly don't know. At the point when I was no longer driving around in circles, when I knew I was going to arrive safely at the destination I had set out blindly to find, that dish became my dish, and I lost interest in any others. The next time I taste it at the store, my mouth will be critical, not ecstatic: I won't be comparing my dish with its but its with mine.

That's the difference between recipe hunting and recipe gathering. You guys will know what I mean.

Shares