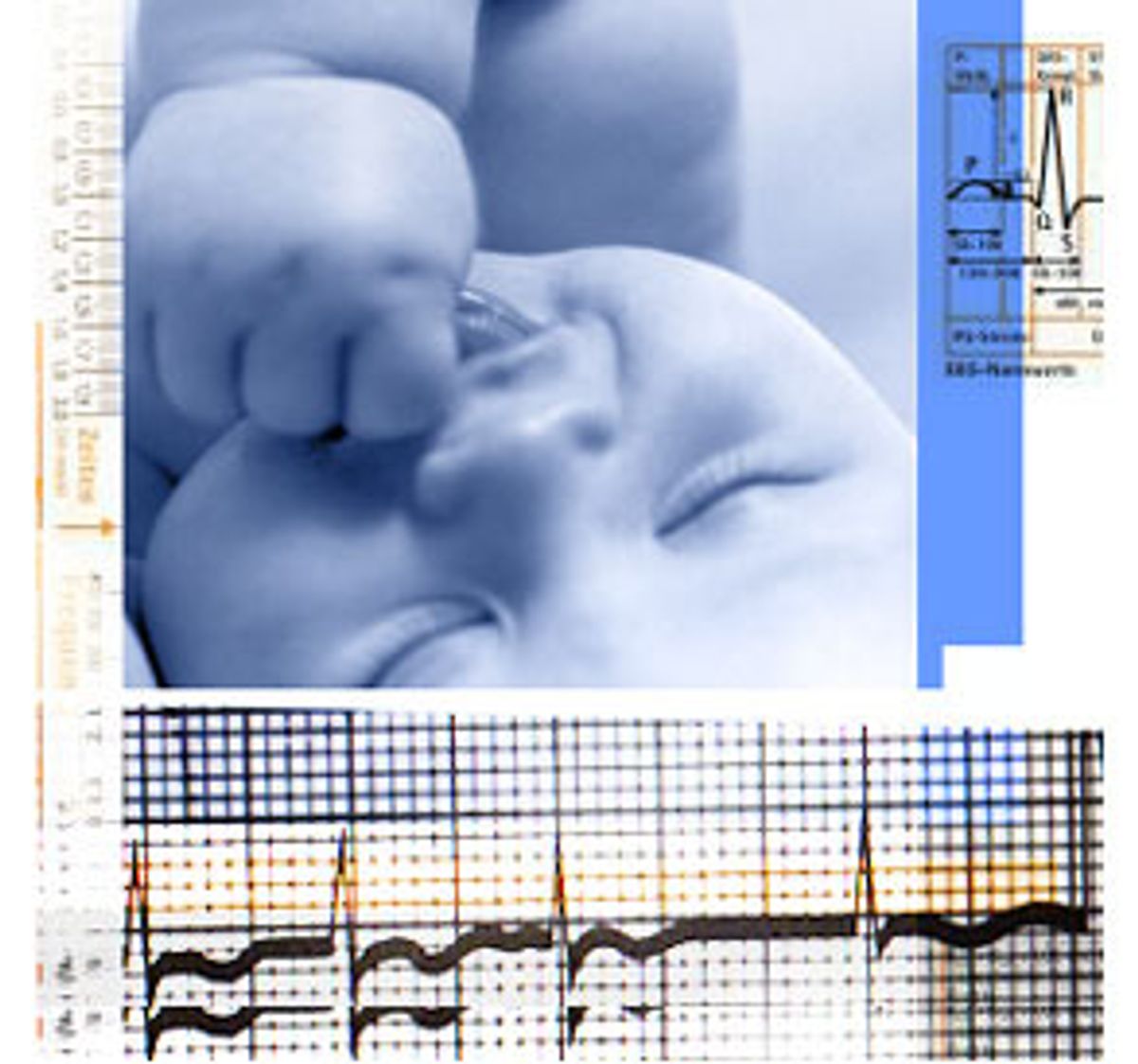

The Pediatric Intensive Care Unit showed no signs of tragedy. Nurses moved about efficiently; a doctor of some sort consulted a reference book; a cleaning lady made big, lazy circles on the floor with her mop. The young couple was nowhere to be seen. Their sorrow must have been centered in another room, out on the "floor," beyond the big double doors of the "unit." Maureen, looking somewhat more rested and less disheveled than I, was already back with Aidan, who was still asleep, flat on his back, head turned to the left, arms bent up at the elbow at either side and tiny fists clenched.

Time unfolded into test upon test and doctors with long faces and few answers. The seizures that were stealing Aidan's breath had gradually diminished and disappeared overnight, thanks to the phenobarbital they had given him. But the cause of the convulsions was still unknown. Blood would have to be drawn to check for a bacterial or viral infection, meningitis perhaps, or encephalitis. Brain waves would be measured by EEG, electroencephalogram. A CT scan was ordered, which would penetrate inside his skull and produce an X-ray of his brain. Other tests would be done as well, a bewildering array of procedures, a plethora of strange new words and acronyms.

Maureen was holding our groggy baby, entangled in wires and tubes, when Dr. Gilmartin (not his real name), a pediatric neurologist, stopped by. His specialty immersed him in the intricacies of children's brains and nervous systems and innumerable insoluble maladies, but the daily tragedies -- seizures, developmental disabilities, degenerative diseases -- had not sapped his humanity. A gentle man, he carefully and quickly examined our little son. We couldn't tell what he was thinking, but nothing seemed terribly wrong; at least it did not show in his face. After reminding us of this or that planned test, he was on his way, maybe to see a child in worse straits.

Gilmartin appeared again late in the afternoon with the first test results. The EEG was normal, with no signs of continuing seizures. No acute problems had been found on the CT scan, either: no bleeding, swelling or growths of any kind. This was all good news and the doctor seemed to be emphasizing the positive by giving us this information first.

But all was not quite right. There was some evidence of a problem in the section of Aidan's brain that connects the cerebral hemispheres and allows the right and left sides to communicate with each other. The bridging structure, the corpus callosum, appeared, in the somewhat sketchy CT picture, to be either underdeveloped or missing, though Gilmartin cautioned that this was not the most reliable test and that a more precise diagnosis could be gleaned only from yet another procedure, an MRI, magnetic resonance imaging.

He went on to tell us that, by itself, the absence of the corpus callosum was not necessarily a disabling condition. Some perfectly healthy people lived full and happy lives without the link within their brains; only upon autopsy was the deficiency surprisingly discovered. In any event, there was not enough information to make a clear judgment, something that would have to wait for the MRI.

I took in Gilmartin's words with an odd sense of optimism. This was, after all, my son whom he was talking about, and I did not feel alarmed nor want to cry or scream. Perhaps my early-morning brush with the couple who had lost their child was enough to make it almost acceptable. Aidan was not dead or dying; he was not in mortal danger like the night before when his lungs stopped. Or maybe it was the way in which the doctor seemed to play down the negative possibilities. What did it mean to be without a corpus callosum? "Normal" people could do just fine without it. That might be our future: Aidan would be fine and the peculiarities of his brain would be our secret; no one would know.

Maureen, too, was not outwardly upset by the neurologist's report, even though she has always been one to focus more on the worrisome "what ifs" of life. There was enough good here to leaven the bad, for the moment at least, and she did not dwell on what might follow; indeed, she, none of us, could know what Aidan's prospects might be. He was only 11 days old, a small bundle of potential whose brain and nerves and cells and all were just beginning to grow in the air and light of day. If others had thrived, he could too.

- - - - - - - - - - - -

We turned our attention to our world outside of the hospital. Things had happened so fast that we had just driven off to Springfield without talking with family or friends. My mother had visited us just two days before the onset and she had returned home believing her first grandchild was healthy and strong. We had not found the time in the midst of the crisis to phone or explain what we were going through. What would we say? What could we say when we didn't know ourselves? More pressing were Maureen's parents. They were due at our home that very afternoon to meet the new grandson, also the first of their children's children. I would have to return as quickly as possible, to be there when they arrived and break the news to them.

I came down our street from the west just as they arrived from the east, and turned into the driveway two car lengths ahead of them. Without taking time for pleasantries, I hopped out of the car and bade them into the house. I knew that they knew immediately it was bad news, but I could not say that Aidan had nearly died; such a start would have been too much.

They had borne enough tragedy in their days, had lost a daughter, their only other child, to an unexpected heart failure. Of course, whether I was blunt or not would make little difference in the long run, but at that moment I tried to put it as gently as possible without deceiving them. Their faces dropped as the words tripped from my mouth, worry straining their eyes. They were not the kind of people who push for details in such situations. Silence has told many tales in their family. No tears, no exclamations, just a few questions -- and they dejectedly settled in for a stay.

This was not the hardest part of that day, however. Shortly after breaking the news to her parents, I called Maureen to see how she and Aidan were faring. As I said "Hi" she gasped in tears. The MRI report had confirmed Gilmartin's earlier suspicion: agenesis of the corpus callosum. The tissue connecting the two halves of Aidan's brain had not developed properly. Other irregularities were found as well. Polymicrogyria, more and smaller folds in the brain than normal, was suggested, as was dysmylenation, or underdevelopment of the sheaths of certain neural pathways. Gilmartin did not elaborate, unwilling to try to predict the future of such a young child, but his expression signified a bad prognosis. Aidan's brain was abnormal; the seizures were a sign of more profound structural problems.

I fumbled for something to say, a reassuring word for Maureen. But the immediate focus of the anger rising within me was myself. I wasn't there at the critical juncture, the time when I most needed to hear and see Gilmartin, to hold Maureen and try to smother our anguish. Instead I was on the telephone, her disembodied voice in my ear and myriad images rushing through my head. What did these terms mean? Agenesis. Polymicrogyria. Dysmylenation. But I told Maureen we would be all right, that I would be there in the morning, that Aidan would be home soon and that we could not be certain that this would be as bad as we might imagine.

Gilmartin's avoidance of categorical predictions held out an unspoken hope. We would have to grasp that for now, not dwell on the dreadful. When I hung up the phone I did not tell her parents of these new details but protectively lied and said things were OK. Then I found my strong, lively dog and took her to lose myself in a harvested cornfield.

- - - - - - - - - - - -

It would take some months before a diagnosis could be confirmed. Gilmartin could not predict with any confidence the extent of disability this peculiar combination of malformations might produce. All would depend on how Aidan developed, how his brain grew. The doctor could say, however, that there was no available research on the effects of agenesis of the corpus callosum and polymicrogyria and dysmylenation. Each had likely ramifications on its own, but the coincidence of all three together was vanishingly rare.

The situation was further obscured by the remote possibility that some of the abnormalities might, with some luck, prove to be less problematic as Aidan matured. What looked like an overabundance of undersize folds in the brain could transform as his brain expanded into something closer to normal, though normality itself was likely impossible. Gilmartin was not optimistic, but neither could he be absolutely sure.

It was with this uncertainty that we returned home after six days in Springfield. Aidan was now 16 days old and heavy expectations hung on every turn of his head. Developmental milestones -- rolling over, holding his head upright, focusing his vision -- took on deep significance. If he could perform certain tasks at something like the right times, it might suggest that his limitations would not be too severe. But if he did not, it could mean profound disability.

He had not had any more seizures since that first night, though we did not know whether they had stopped of their own accord or because we continued to give him phenobarbital. The red elixir looked like it might taste good, with a cherry flavor perhaps, but it burned the back of the throat, making even adults gasp. For an infant it was a daily ordeal, a raw intrusion upon body and spirit.

Holding Aidan tightly on my lap, I would find a way to tilt his head back and gently work the tip of the syringe into his mouth. It was a small dose, 2 or 3 milliliters, and I found that I could slip it in between his cries and be done with it in a minute or two. He would fight with all of his strength, arching his back and shaking his head. However much his cries tore at my heart, I persisted, hoping upon hope that somehow this would help him.

Various medical devices had accompanied us home. The most nerve-racking by far was the apnea monitor. Simple enough, it consisted of a small strap that fit around Aidan's chest with two electrodes resting just above his tiny nipples. Wires ran from the electrodes to a small bedside box that kept track of his respiration and heartbeat. It could be set to measure the interval between breaths, and if this lasted longer than, say, 30 seconds, a screeching alarm, something like a smoke detector, would shatter the calm.

The infernal machine produced more false alerts than helpful warnings, however. For a couple of months, we kept it on him day and night -- after all, it had been a serene morning when he had first stopped breathing -- but as time went on we used it only when he was asleep. It regularly burst in upon our slumber. Maureen was so intensely attuned to it that, I swear, she could anticipate its awful noise and surge out of bed onto her feet before the first electronic impulse hit the air. We struggled with a variety of electrodes and many different positions in a vain attempt to improve its accuracy, and lived with its unforgiving demands for eight months.

Common baby gadgets were transformed by our situation into quasi-medical equipment. We found that the walkie-talkie set used by most parents to hear when their napping children awake could monitor Aidan's breathing. By turning the receiver to maximum volume, we could listen to the reassuring puffs of air moving in and out of his chest. All around the house, wherever nap-time chores would take us, the little white and blue speaker gave forth the staticky hiss of his breath. It was an odd sort of reversal: we straining to hear the sounds of sleep while others waited for the first signs of wakefulness.

The baby books were similarly remade into their opposite; instead of providing a record of progressive development, for us they chronicled, in excruciating detail, our slow realization that Aidan was not gaining basic motor skills and cognitive capacities. At 9 or 10 weeks old, the books told us, Aidan should have been able to roll from his side to his back with some facility. By 3 or 4 months, he should have been grasping for objects. At 5 or 6 months, he should have been able to bear the weight of his head and shoulders on his forearms while lying on his stomach, an important prelude to crawling and standing.

None of these things was happening, though he would occasionally get himself from his side to his back, but never from his back to his side. Once, when he was about 3 months old, while prone on a large flowery pillow next to Maureen's mother on the living room couch, he raised up his head and turned it from side to side. It seemed at the time that it might be a breakthrough, the beginning of the wondrous chain of physical actions that culminate in the full range of boyish activity. But no. He hardly ever repeated the move in quite the same way.

Our ability to gauge his progress, or lack of it, was hampered by the fact that this was our first child. We had never been through, in such an intimate manner, the stages of early childhood development. Without the experience that would have provided certain points of reference, we watched as the days slipped by with virtually no physical or cognitive change, unable to appreciate fully the accumulating signs of profound limitation and not wanting, really, to know just how far behind he was falling. We were too afraid to draw the increasingly evident conclusion that Aidan would be seriously incapacitated.

- - - - - - - - - - - -

Aidan is 9 years old now. He cannot see, stand, walk or speak. Maureen and I have followed him through experiences we could never have imagined when we were just starting out, fresh-faced new parents full of expectation for our firstborn son. We have seen too many emergency rooms and intensive care units and postoperative floors and doctors' offices.

But we, and he, have done more than just survive. We have learned, from his silence and stillness, that good lives take myriad forms, that what appears to be stultifying limitation to some is simply a reordering of the most basic human needs and rhythms. He sleeps, wakes up, takes nourishment, has friends, is loved and can love in return. His severe disability has transformed our worldview in ways that call to mind a passage from fourth century B.C. Chinese philosopher Chuang-tzu, for whom the concept of the "Way" encompassed the complex unity of nature:

"The blade of grass and the pillar, the leper and the ravishing beauty, the sniveling, the disingenuous, the strange -- in the Way they all move as one and the same."

Shares