As hundreds of people gathered last weekend to mourn the deaths of two students at Santana High at the hands of a fellow student, Attorney General John Ashcroft mournfully revealed to the press more surprising news about the school's violence problems. It seems that the high school in Santee, Calif., was in the process of using a $123,000 Justice Department grant to study what Ashcroft described as an "onerous culture of bullying."

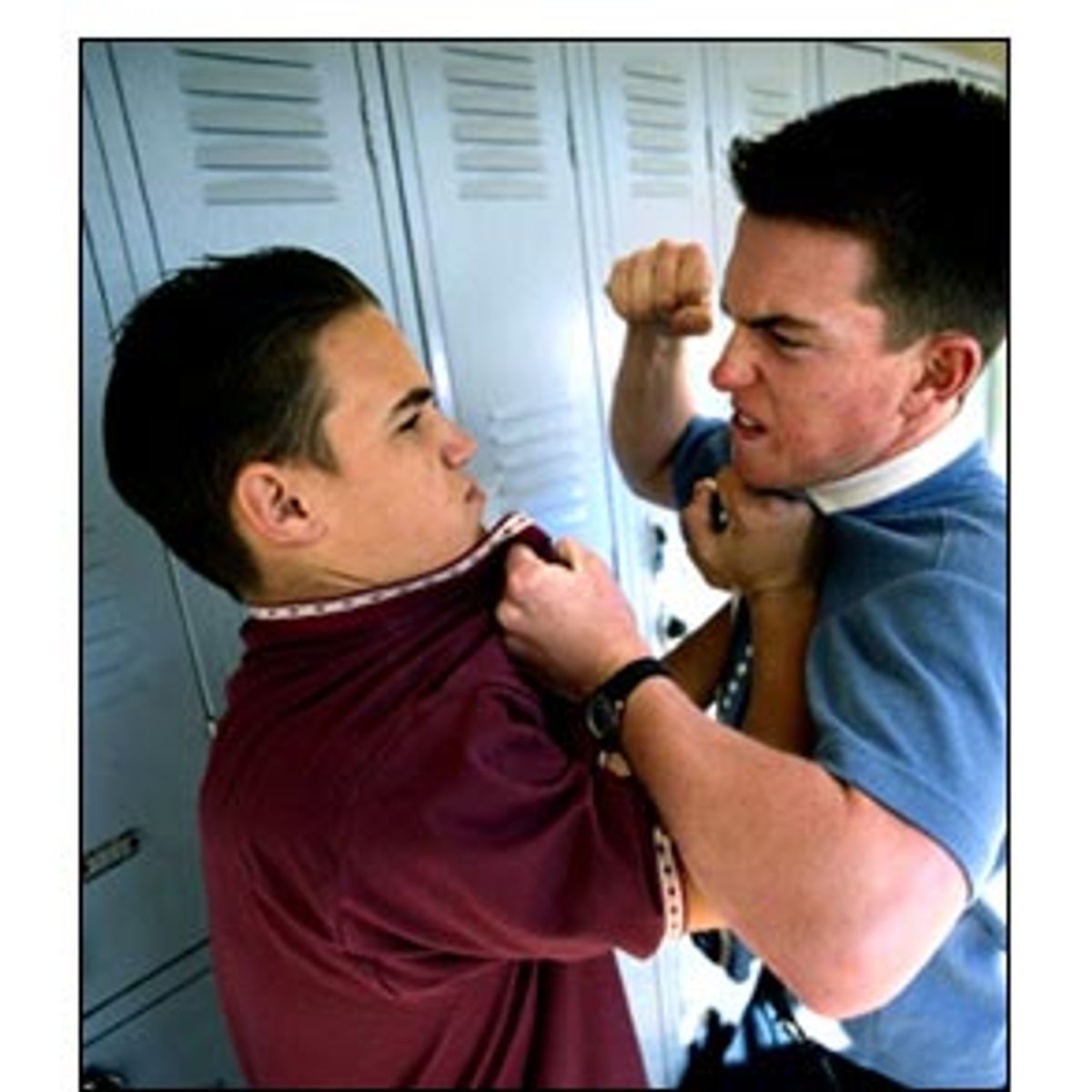

The grant became news because classmates of Charles Andrew Williams described the 15-year-old freshman and alleged shooter as a kid who'd been bullied to the breaking point. The description is strikingly similar to those given by friends and fellow students of Columbine killers Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold. Both boys were reportedly mocked and taunted routinely and sought revenge through a deadly plan against their fellow students. News also surfaced this week that Williams had saved one bullet in the attack -- reportedly for himself.

Some of Williams' classmates insisted that he was no more tortured than any other student at the school was. The disagreement about Williams illustrates one of the chief problems with efforts to crack down on bullying: It's sometimes hard to agree on what constitutes bullying and who's behind it.

In spite of that confusion, school reformers have floated a roster of anti-bullying measures in the wake of Columbine and, now, Santana. State legislatures in Colorado, Washington and California are taking action with school safety bills that would mandate programs in local school districts to target the bullying problem. Some schools, including Santana, have also turned to a Justice Department program called Community Oriented Policing Services, or COPS, which provides grants to help schools study campus violence.

Santana High School faced a widespread problem with student harassment years before Williams arrived at the school. A 1997 survey taken by the San Diego County Sheriff's Department found that half of Santana's students didn't feel safe on campus, 35 percent said they had been the victims of verbal abuse or insults and 12 percent said they had been physically threatened or intimidated. More than a third said they had experienced problems directly related to race or ethnicity.

Sadly, this sounds a lot like what's going on at high schools all over the country. Despite the remarkable decrease in juvenile crime over the past decade -- culminating in the lowest juvenile homicide rate since 1983 -- students and their parents feel a great deal of fear. According to a Gallup poll taken in October, the number of teenagers involved in fights is declining, but more and more of those fights are happening at school. Two-thirds of students said fights at school were a "very big" or "fairly big" problem; 89 percent of those who had been involved in fights said they felt they had to stand up for themselves.

Increasingly, schools, states and the federal government are taking action to curb the disturbing trend.

Back at Santana High, the problem seemed to be growing. According to Gilbert Moore, spokesman for the Justice Department's COPS program, which administers the grant, problems with bullying had been escalating at the school. From January 1997 to May 1998, "the local sheriff's department noticed that there had been a noted increase in the victimization of juveniles both on the campus and in the surrounding neighborhood," he says.

So the county sheriff's office and the city of Santee applied for a school-based partnership program grant that would help them assess the source of the problem. In cooperation with the sheriff's department, Santana High has used the grant to pay a small stipend for a student coordinator, who interviewed students about their experiences being bullied; a crime analyst; a crime prevention specialist; overtime for at least one police officer who worked with school officials and community groups; and equipment such as a computer, scanner and projector.

Moore emphasizes that the program is not geared toward dictating solutions -- such as ramping up police patrols -- but toward finding out what the root of the problem is. The "multifaceted approach" of the grant program is designed to get community groups, schools and police in contact with the students. "This whole concept of the discipline of school violence and school safety is evolving," Moore says, "and it's evolving because it's been thrust in the lap of the country. We like to think that we're in a leadership role in terms of getting law enforcement to focus on it and helping them get started addressing the problem."

Santee was one of 322 applicants in 1998, only half of whom received a grant. Five percent of the grant money will pay for a formal evaluation to be sent to the Justice Department. But once that analysis is in, it will be up to the community to decide what to do about it. With two teenagers now dead and the eyes of the nation watching Williams' impending trial, the conclusions they come to are likely to be influential.

Meanwhile, school safety bills under consideration in Colorado, Washington and California would mandate programs in local school districts to target the bullying problem. The California bill adds a policy for preventing bullying and a conflict-resolution program to the state's existing school safety code. Colorado's bill, which has passed the state Senate and awaits a vote in the house, would require each school district to draw up a specific policy to address bullying prevention and education. Washington's legislation goes a step further, saying that each district's policy must explicitly prohibit harassment, intimidation and bullying, and set out a procedure for reporting and responding to it.

Jaana Juvonen, a social scientist at the RAND institute, has studied school bullying for several years. She says she's not surprised by tales of school shooters who are bullied to the point of violence. "Most of the victims suffer in silence. The minority of them do retaliate," she says. In those extreme cases, Juvonen believes, kids essentially don't know of another option to deal with the situation -- they don't know how to resolve the conflict in which they find themselves, and they act based on the models they have around them, whether that be violent video games or violence at home.

Juvonen is supportive but skeptical of violence prevention programs in general, arguing that their success depends greatly on their approach. "All kids can benefit from conflict resolution education and learning about strategies to deal with peer ridicule," she says. But if the programs attempt to single out the bullies, they can do far more harm than good by making schools an even harsher place for kids. Targeting the problem kids is "very problematic" because it involves two assumptions. "One is that we can reliably and validly identify youngsters who are at risk -- I'm afraid that's not possible. If we use those kinds of identification procedures, we will overidentify kids and mislabel them," Juvonen says.

The other problem with that approach is what happens next. If schools weed out those students and put them all together, "we may actually increase their risk of antisocial and delinquent behavior," Juvonen says.

Her research shows that most kids in school are victims, and a minority are bullies. But an even smaller number are both. "It's the last group who are really at risk for a multitude of problems." After the Santana shooting, Education Secretary Rod Paige told reporters that he believes students' "alienation and rage" is the biggest factor in school shootings. But in trying to stem that rage with mandated school programs, the government could be entering into rough territory.

Some argue that bullying has always existed, that it's just part of growing up, and that trying to legislate human behavior is a no-win endeavor. What's more, kids are often reluctant to come forward and tell teachers about what they're going through (Williams, for instance, never reported that he was being bullied). The complex power struggle among kids tends to be invisible to the adults around them.

Researchers on youth violence caution the government against generic solutions to the problem of bullying. Among the most contentious are approaches that focus on punishing or excluding problem kids, whose troubles usually source back to violence or abuse at home or in their neighborhoods. Even taking into consideration the argument that bullies should be held accountable, sending them back into an environment of street violence, abuse, drug use and other delinquent kids tends to increase the harm they will visit on their peers.

No matter what solutions local districts come up with, it seems clear that schools will continue to bear much of the burden for some very big societal ills.

Shares