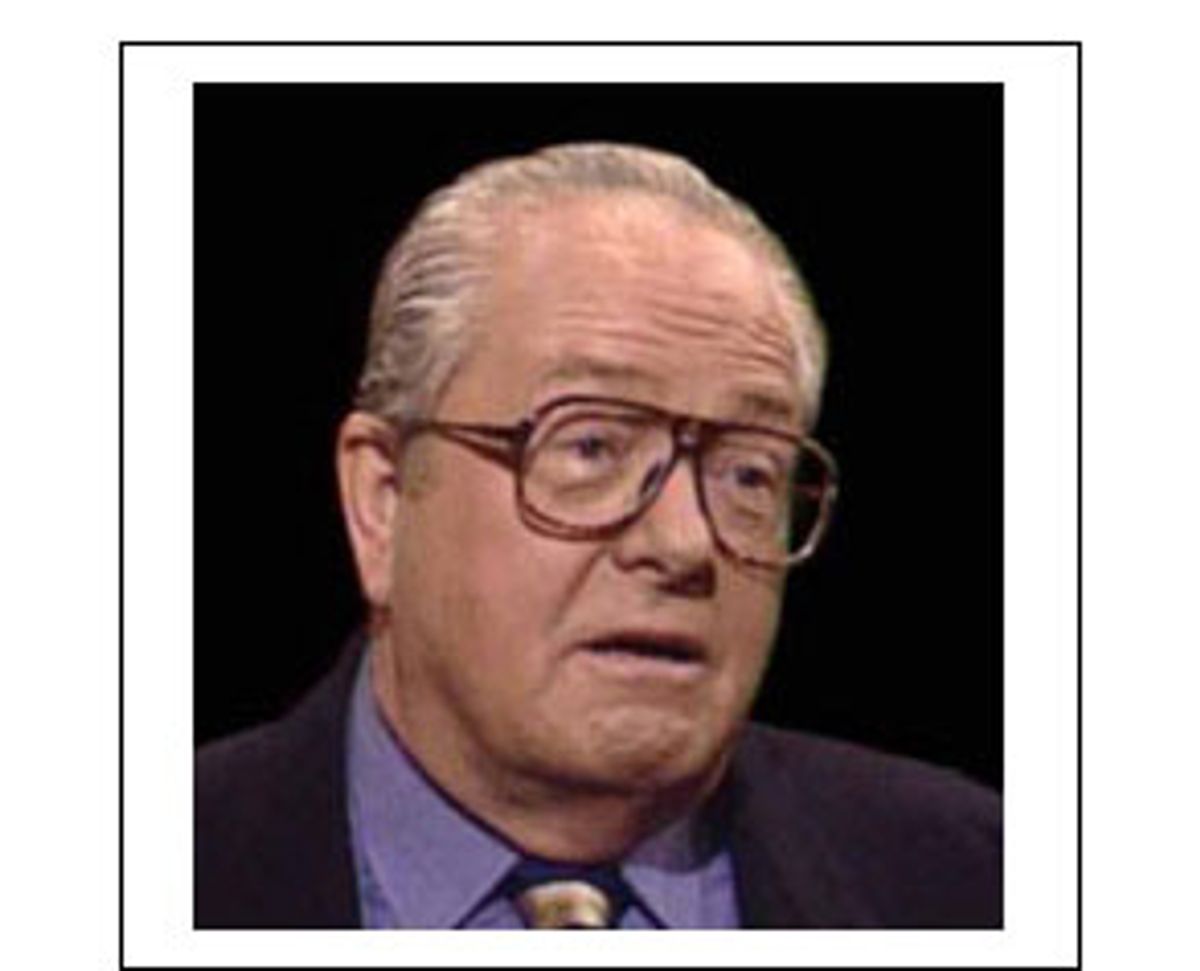

Ever since Jean-Marie Le Pen first stormed the National Assembly as a raucous law student in 1956, the extremist National Front leader has tormented France's right-wing political establishment, which is embarrassed by his raving anti-immigrant views. But Sunday's presidential election marked the first time Le Pen managed to wreak havoc in the ranks of the left.

Receiving an unprecedented 17.8 percent of the vote in the first round of the election, he handed a resounding defeat to France's Prime Minister Lionel Jospin and to the entire establishment left that has been the cornerstone of the French government for the last five years. There is a chance, of course, that the May 22 legislative elections will redeem the prime minister's brand of pragmatic socialism, but it's just as likely that the entire center-left coalition has become political history.

Most of the headlines were about Le Pen, but the extreme left also scored a major victory in Sunday's elections, with Arlette Laguiller, the retired bank clerk and eternal maverick of French politics, snaring 6 percent of the vote. Altogether, the far left, including the forlorn Communist Party, managed to snag over 15 percent of the voters from the mainstream Socialists and their pedantic figurehead Jospin.

Le Pen's victory is relative, however. What's most true about this election is that there were no real winners. To begin with, he scored barely 2 percent more than he managed in the 1995 contest, and it is widely acknowledged that there is no way he can beat incumbent President Chirac in the final round of the race May 5. Just about every other political leader has already called on his or her electorate to "sustain the values of the Republic" and to "preserve the honor of France" by leaving Le Pen in the dust. It is only the ineptitude of the Socialists, and more generally the lethargy of their usual constituency, that has allowed the ex-paratrooper turned populist authoritarian leader to reach the second round of an otherwise mind-numbing election.

With some 17 candidates from all walks of French civil society, from the Hunting, Fishing, Nature, and Traditions Party, which managed to glean 4 percent of the vote, to various environmentalist factions who couldn't manage to endorse one single candidate, to Catholic advocates and extremists from every horizon, this election was an embarrassing fiasco long before the final votes were ever tallied. Indeed, most observers of French political life agree that the two-round system, instituted by de Gaulle as a vehicle for his own reelection, has seen its day. With nothing other than the required 500 signatures from municipal officials required to run, there is theoretically very little to prevent any number of "candidates" from using the presidential race to promote their various agendas, which range from the most trivial (establishing more lenient hunting regulations) to the most revolutionary (establishing a proletarian dictatorship). Without a profound institutional overhaul, France is doomed to replay such a parody of democracy at every presidential ballot.

On Sunday, 10 million registered voters suffering from election overload -- out of a total population of 60 million -- just couldn't be bothered to cast a ballot. Although some of the blame undoubtedly rests with Jospin himself, an ex-professor who is at best a mediocre communicator unable to stir Socialist ranks after five years of lackluster, if dogged, leadership, the two-step system was clearly a factor. Having to vote twice is a burden most constituents would rather avoid, and no one, probably least of all Le Pen, imagined that anyone besides Jospin and Chirac would face off for the second round. So the French, many of whom were on Easter break, decided to take a vacation.

On Belle-Ile, an island paradise that lies only a few dozen nautical miles from Jean-Marie Le Pen's hometown of La Triniti-en-Mer, multitudes of vacationing Parisians were ambling the streets on Sunday, taking time off for spring break and enjoying the good weather far from the bustling voting centers of the City of Lights. The fact that Belle-Ile lies some 600 kilometers from the capital didn't dissuade the tourists and owners of secondary homes crowding the marketplace from taking a vacation during the first round of the presidential ballot. All of them, like Henri Carron, an intellectual property lawyer who lives in the fashionable Marais district, just took for granted the second round would oppose the two politicians who have clogged the forlorn French political landscape for the past seven years. And Henry Carron, like all the other "continentals" on Belle-Ile, did not have an absentee ballot.

"Why should I vote twice?" he says. Now, presumably, he knows.

Like Henri Carron, an overwhelming number of middle-class French liberals who favor Lionel Jospin because of his "honesty" and "work ethic" will now have to choose between a worn fixture of old-school French power politics accused of corruption and a street thug who liked nothing more than to beat up rival student leaders in the '60s, and who not so long ago defined gas chambers as "a detail of history" and called for the incineration of a Jewish government minister. To say that the country is in a state of shock would be an understatement.

Serge July, perhaps France's most famous editorialist, and the director of the center-left daily Libiration, summed it up in a nutshell:

"You should know: France is a country that is clueless, panicked, afraid of its own shadow, and which, politically, is incapable of facing the future."

Paradoxically, it is violence perpetrated against Jews and Jewish institutions by second- and third-generation immigrants of Arab extraction as a result of the situation in the Middle East that helped Le Pen beat the opposition. He has always been a staunch law-and-order advocate (despite his own problems with the law), and Chirac as well as Jospin have been forced to follow in his tracks, making security and rising crime rates the biggest issue of these elections. But, as Le Pen says, "The French have always preferred the original to the copy," and allowing "the big Celt" to define the terms of the debate virtually guaranteed that he would win the debate.

Le Pen's real victory, in fact, is that all his old battle-horse issues -- immigration, globalization, American domination and the European Union; all the menaces that are robbing France of its identity -- have come to dominate French politics, and indeed to define French society.

France, today, is indeed a far cry from the righteous, patronizing nation that lambasted America for allowing the election of President Bush after the contested Florida vote, or threatened to boycott Austria after Jvrg Haider, another effigy of the European extreme right, was elected to national office. Compared to Le Pen, Bush is a civil libertarian and Haider is a flower child, and the French know it better than anyone. So many French feel humbled by his ascent. Cloaked in a new veneer of respectability, Le Pen is still considered by the vast majority of the French to be a dangerous autocrat and a racist. But he is also one of two men vying to be the next president of the country that drafted the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, and as such sees itself as the birthplace of civilized society and the spearhead of egalitarianism.

Speaking of the necessary "guilt of the absentees and the undertakers of the Left," Serge July concluded his scathing editorial with a brutal assessment: "French democracy is in a coma."

Many are hoping the big bruiser from Brittany will wake her up.

Shares