Hollywood stud-boys are generally too boring (Brad Pitt), too weak (Ashton Kutcher), too all-things-to-all-people (Will Smith), too adolescent (George Clooney), too humorless (Russell Crowe), too delicate (Jude Law) or too stupid (Kevin Costner). They've done too many test audiences with weepy, overweight girls from the Midwest or something, and now most leading men are too accessible and nice -- threatening, broody, strange, potent, complicated masculine energies are almost entirely missing from the screen. Intense, intelligent leading men are apparently too challenging for American audiences, who want their male stars likable and familiar, and are apparently put off by internal conflict or complexity. Thinking women are stuck with intractably grumpy, macho hicks; gleeful, overgrown teen clods; smug pretty boys; and wispy, cologned metrosexuals to project their fantasies onto. Unless they want to go foreign.

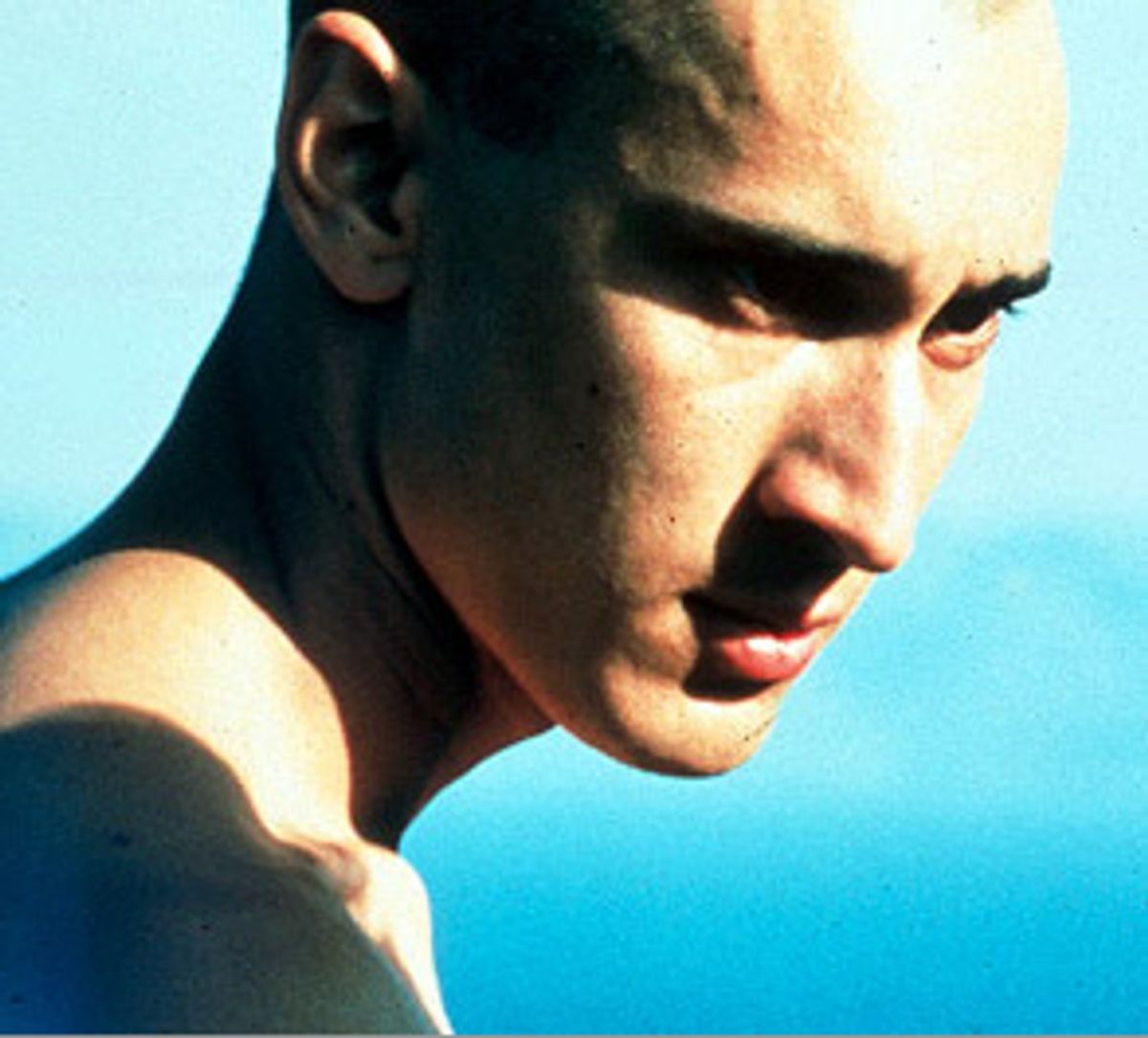

Which is why I love French films, and Grigoire Colin. He is more exotic-looking than Hollywood stars are allowed to be: long face, Asiatic eyes, an elegantly large, aquiline nose, Faye Dunaway cheekbones; small, round mouth -- like a living Modigliani. Trying to describe his unusual features by a combination of ethnicities, one might try French-Jewish-Japanese-Siberian; his face is a combination of mismatched features that shouldn't work, but is unexpectedly magical. A good deal of Colin's films contain doting landscape shots of his naked body, the musculature of which might be composed of windless sand dunes -- a vulnerably natural, velvety, soft-edged hard-body that reflects a purer, more classic and subtle aesthetic than the cut, dyed, gym-bot, briskety sinew of Brad Pitt, whose physique, like the modern architecture he loves, looks miserably uninhabitable.

Aside from his obvious physical gifts, Colin, who began acting on the French stage at age 12, brings something to the screen that American stars can't -- range, emotional courage; fascinating choices. Colin takes risks that would paralyze American stars with insecurity. He turns, film to film, from priest to rapist, thug to sophisticate, innocent to bastard -- clean, precise, complete transformations, gorgeously built from the inside out. It is as if Colin's soul is as clear as water, free from the various inner tattoos and inhibitions of ego and personality that would prevent him from inhabiting a character completely -- totally unlike an American heartthrob, who would wear different costumes but basically play small variations of himself in every film.

In "Olivier, Olivier" (1992), Colin, just 17 at the time, delivers an intricate, skilled performance as a boy who runs away from his screechy, melodramatically dysfunctional family at the age of 9, and returns six years later, having lived in the meantime as a gay bus-station hustler. Colin is able to project a dippy teen innocence at the same time he is delivering a sleazy, too-knowing bedroom stare-down. He floats back and forth between a deceitful, abused sexual menace and a quivering vulnerability -- an unfortunate kid for whom seduction, both emotional and physical, is survival. It's shockingly sophisticated and well-observed inner work, especially for a teenage actor. He recites a poem at one point, articulating each emotional turn like a seasoned Shakespearean on a freshly paved textual autobahn -- hair-raisingly impressive.

"Before the Rain" (1994), directed by Milcho Manchevski, is an interesting triptych of stories of people affected, in different and far-reaching ways, by religiously motivated violence in Yugoslavia. In it, Colin is so beatific and flawlessly pretty as the young Macedonian priest Kiril, his face evokes a better-lit version of a pious Audrey Hepburn in "A Nun's Story." Kiril, who has taken a vow of silence, hides in his quarters an Albanian runaway girl who is being sought by armed packs of feuding locals. Colin has no lines; Kiril's entire inner journey -- a love that grows from general (humankind) to specific (the girl), with its agonized suspense, betrayal, deep faith, shattering loss -- is conveyed through his glittering eyes, so dark as to look all-pupil, like jet buttons housing tiny suns.

"Son of Gascogne" (1995) is a charming little treasure of a film by Godard protigi Pascal Aubier. At 20, Colin still looks like a gawky adolescent, all wrists, nose and knees. Harvey (Colin) is an innocent, fatherless tour guide, leading a pack of hollering ex-Soviet Georgians around France. He is convinced by a louche, gold-chained limo driver that he is the illegitimate son of "Gascogne," a famous, deceased bon vivant from the era of French New Wave cinema. As Harvey gets dragged around Paris and introduced to Gascogne's (and presumably director Aubier's) famous old friends -- New Wave stars like Anna Karina, playing themselves -- he grows fond of cashing in on the residual star power of his long-lost playboy father. It is a Cary Grant role -- madcap, exasperated, romantic, with lots of yelling and arm waving -- and Colin pulls it off with impressive timing and control, particularly in a scene in which two hot older women get him drunk and seduce him in a hot tub. The shy, geeky wonder and gee-whiz surprise on his face as the women undress him is a prime example of the understated, selfless commitment with which Colin serves his films; a young male star in the United States would be too egocentric, too scared of looking uncool, at this point in his burgeoning career, to let himself look like the naive goofball that "Gascogne" required.

"Nénette et Boni" (1996), Colin's first collaboration with director Claire Denis, is an odd little film about a hot brother and sister, brought up under strange and unspecifically bad circumstances. Nénette is a pregnant teenager; Boni is an angry, perverted pizza-maker, obsessed by fantasies of raping a local bakery woman who happens to be married to Vincent Gallo, who is basically playing himself, baking croissants in Paris for no good reason, and whining about it in his famously nasal Gallo way, as if he is selling discount menswear in Yonkers. It is a particularly ridiculous piece of casting that suggests that Denis abused her power as director in order to surround herself with pretty young men, and God bless her for it.

This is Colin's most seething role -- he is so frustrated and horny one can imagine baseball bats sweating out of his perfect skin. He performs a really nice, difficult transformation. Boni and his sister, both rootless, strange children with no intimacies, forge a kind of vile alliance with each other. Boni becomes interested in Nénette's unborn child; it stokes a tenderness in him that is on the opposite end of the emotional spectrum from his abusive sex fantasies.

There are a lot of scenes of Colin, as there are in a number of his films, shirtless, masturbating. He talks to himself while he does it, sneering as if he was forcing Mrs. Gallo to perform perverse acts on him. When confronted with the wife in person, he can do little but stare at her with powerless hunger.

At the end of the film, Boni finds a strange pleasure in holding his sister's newborn child. It is Colin's delicacy that lets you know that Boni, for all his hard-up, frustrated rage, isn't a sicko. He tells the baby, with infinite tenderness, "You pissed on me. Yeah. You know that? You pissed on me." It sounds like familial love, and not grounds for a potential child protective services intervention -- something of a small miracle.

"Secret Defense" (1998) is an ambitious mess of a film with extremely clunky emotional logic, starring a brittle and overwrought Sandrine Bonnaire playing a scientist who plots unlikely violence after her brother Paul -- a broody, thuggy, track-suited Colin -- convinces her that an old family friend, played by Jerzy Radziwilowicz, killed their father. It is one of Colin's least dimensional roles; Paul is quiet, stony-faced, stubbornly obsessed with revenge. There are bizarre scenes in which Bonnaire throws infuriated, shrill, screaming tantrums at her brother while he stares back at her, unmoved by her hysteria. Colin is able to transmit the impenetrable, bullheaded rebelliousness and monomania that are the earmarks of an angry young man, but there is not much else for him to do; the film meanders weirdly and never coheres. (The turquoise-eyed Radziwilowicz is the most compelling animal on-screen; slightly pudgy, urbane and full of paradoxes, he radiates an interesting, Bill-Clinton-but-more-ethnic, middle-aged sexiness.)

"The Dreamlife of Angels" (1998) is a total bummer, one of those films that makes you feel like you're slowly swallowing an entire live frog made of poorly imagined human pain. It is, however, Colin's most frankly carnal role; there are a lot of sweeping camera crawls over his marvelous body, having feral sex with a miserable, thrashing blonde, played by Natacha Rignier.

Colin brings nice complexity to the role of Chriss, a rich, sadistic playboy toying with the unstable emotions of poor factory girls. We only see him acting polite and reasonable; we, the audience, somehow just know, despite the fact that Chriss shows every sign of caring about the blonde, that he doesn't really care about her. He smiles, he kisses, he gently whispers, "Doucement, doucement," when she is trying to scratch his face off while he's screwing her.

Colin looks preternaturally amazing in this film, leaning against a bar with his sexual stare, a dark purple silk shirt bringing out an iridescence in his glossy black hair and olive-yellow skin. It's a sinister, super-concentrated, energetically charged male beauty that renders the viewer awestruck -- Colin is the only human I can think of who could single-handedly upstage a pair of lions mating.

"Beau Travail" (1999), a loose interpretation of Melville's "Billy Budd," is another rhapsodic ode by Claire Denis to Colin's unclothed body. Colin is Gilles Sentain, a charismatic hero in the foreign legion, who finds himself on the bad side of a jealous, ugly, abusive commanding officer, who opts to make Sentain's life in Djibouti miserable because the other men admire him too much. The film is as muscular, dirty, shaved, artsy and homoerotic as any Bruce Weber campaign, and must viewing for anyone interested in wallpapering their bedroom ceiling with images of Colin's torso. The role calls for him to be saintly and "Cool Hand Luke"-ish -- a strong, silent, long-suffering, unbreakable stoic, blister-lipped and dying of thirst on an endless, cracked expanse of desert salt flats.

Benoît Jacquot's "Sade" (2000) is a great film, centering on the incarceration of the decadent Marquis with other aristocrats awaiting the guillotine at Picpus, during the Reign of Terror. Colin plays Fournier, Jacobin deputy to Robespierre and rival of Sade for the affections of a hot, cat-faced woman. Sade, in this tale, is depicted as a thoughtful, life-and-freedom-loving philosopher. Colin's Jacobin is a man enslaved to his own hateful weakness -- he is jealous and sexually brutal to their mutual girlfriend. Sade, in a rather obvious reversal, is gentle, respectful and tender with her. Colin actually succeeds in making himself unattractive here; his eyes look completely different than usual -- beady, ratlike. His nose is sharp and beaky, he holds himself in concave postures of deep self-loathing and insecurity. He is nearly unrecognizable; his very aura is different than it is in other films.

The Bogart-like Daniel Auteuil, as Sade, is marvelously comfortable in the cerebral role of the reckless, liberated artiste; but the unearthly Isild Le Besco steals the film as Emile de Lancris; she is the most singularly beautiful inginue since Olivia Hussey's Juliet, and thrillingly smart. I predict great things for this young actress; she has strange, perverse fire behind a face that is Zen-like and serene in its perfect symmetry.

I was unable to locate any copies whatsoever of "Snowboarder" (2003) (but if the title is any indication, it is yet another volte-face for Colin, who usually doesn't participate in such fad-fodder), and while 2004 gave us "L'Intrus" ("The Intruder"), another Claire Denis film with Colin, it is not yet available in the U.S. He is in production on more French films, which can be tracked through a rather humble, if devoted, American fan Web site.

With any luck, Colin will appear in some English-speaking role eventually, but I somewhat doubt it -- an actor of Colin's intelligence knows better than to muck around in the cultural tar pit of Hollywood. In France, Colin retains his eclectic choices and his integrity, and probably sees no reason to trade that in for the falling currency of Hollywood celebrity.

Anyway, reading subtitles over a nude Grigoire Colin will never be a chore.

Shares