Former Democratic National Committee chairman Terry McAuliffe is a brash and unabashed self-promoter, who has utilized those gifts to become the best fundraiser in the modern history of his party.

New York Sen. Chuck Schumer is an aggressive and unashamed publicity hound, who has utilized those qualities to become the most successful self-made politician in his home state and the architect of the Democrats' 2006 Senate takeover.

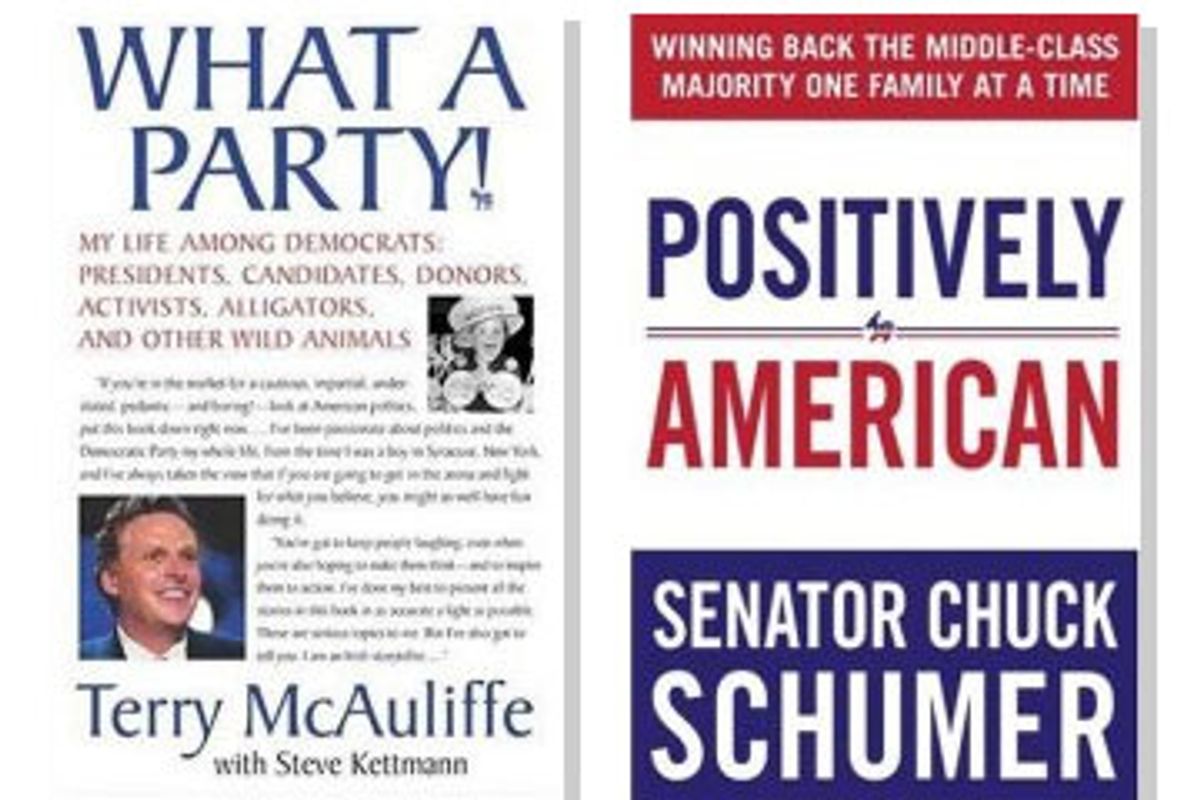

Given the similarities between a book tour and a political campaign, it is probably not surprising that both McAuliffe ("What a Party!") and Schumer ("Positively American") have just become published authors. Pity any self-effacing literary novelist who might have to compete with the salesmanship of McAuliffe or Schumer at a Barnes & Noble book signing. But the real irony of the publication of both of these books on the same day is that comparing one to the other points up an underlying, unresolved tension as the Democratic Party seeks, yet again, to define itself. The issue is money.

The exclamation mark in the title of McAuliffe's book is comically redundant, since everything the man does is broadcast at high decibels. This midlife political memoir has a rollicking style and captures McAuliffe's voice, and on the surface seems like nothing more than a diverting book to carry on a cross-country flight (preferably aboard Air Force One in a Democratic administration).

In "What a Party!" McAuliffe pitches himself as a Horatio Alger hero for the 21st century. Whatever the obstacle, beginning with his teenage career paving driveways in his hometown of Syracuse, N.Y., McAuliffe triumphs through boldness and pluck. A typical sentence describes the reaction to a McAuliffe fundraising scheme for Bill Clinton's 1996 reelection campaign: "Everyone in the Map Room meeting besides the President and the First Lady thought my plan was too aggressive." An emblematic moment in the book is McAuliffe sitting with Bill Clinton on the Truman Balcony of the White House as the president turns to him and says, "You know, Mac, we've done all right. Not bad for two kids from the sticks."

Schumer's "Positively American" also contains its share of well-told political narratives, particularly the backstage account of the author's 1998 upset Senate victory over Republican incumbent Al D'Amato, an old-fashioned patronage politician. Unlike the lighthearted McAuliffe, however, Schumer also has a serious political agenda that extends far beyond short-term victory. Having nearly run the table in the 2006 elections, picking up six seats to give the Democrats a fragile one-vote margin in the Senate, Schumer now wants to create an enduring majority by establishing the Democrats as the party of the middle class, and "Positively American" is his manifesto.

Schumer's eureka moment came during the 1998 elections. Then an incumbent candidate for the U.S. House from Brooklyn, Schumer grappled to explain to his advisors what he meant by calling himself a "meat-and-potatoes Democrat." Finally, Schumer said in exasperation, "Look, there's a voter out there. He doesn't belong to the ACLU, he doesn't march for abortion rights, he isn't a member of the Sierra Club, but he votes. He's got a mortgage and property taxes. His wife works, in part, because she wants to, but mostly because she has to."

Schumer devotes half his book to proposing a new Democratic policy agenda to appeal to the needs of what might be called the forgotten middle class -- families earning $50,000 to $75,000, who are neither poor nor economically comfortable. His boldest idea is to triple federal investment in education both to raise standards and -- more important politically -- to lift the local property-tax burden on these middle-class voters. In Schumer's view, the property tax "hurts the middle class like nothing else does ... For a lot of families the day that their property tax bill is due is their defining interaction with the government each year."

And there is the irony in reading Schumer and McAuliffe's books back to back. For all the easy political rhetoric about "fighting for the middle class" and "the people vs. the powerful," the Democrats depend heavily on the financial support of the wealthy, from New York hedge-fund managers to Hollywood producers to tort-shopping trial lawyers. The quid pro quos may not be nearly as naked as among the Republicans, but Bill Clinton did not fund two $100-million-plus campaigns (not to mention a presidential library) with bake sales and tip jars.

For readers interested in the nitty-gritty mechanics of asking the rich for money, Terry McAuliffe does not provide too many details. Instead of discussing technique, he drops names. When the Clintons in 1999 needed private money to pay for a turn-of-the-millennium party on the Mall in Washington, McAuliffe rushed to the rescue: "After four months of effort we raised $17 million, helped by a $2 million gift from Vin Gupta, a man who was born on a dirt floor in India ... Danny Abraham, the founder of Slimfast, also gave us a million." From McAuliffe, we learn who gave the money, but rarely the whys.

Sometimes just the names of the givers arouse a certain degree of skepticism. Just two pages after McAuliffe accepts the challenge to raise $100-million-plus for the Clinton Library, there is the author at the home of Prince Bandar, the legendary ambassador from Saudi Arabia, enjoying a dinner party in honor of Nelson Mandela. While Bandar is famous as a friend of presidents (elaborate conspiracy theories have been built around his relationship with the Bush family), there has been, prior to the McAuliffe book, scant evidence that the Saudi prince had been a passionate foe of apartheid.

The point is not to flog the naive notion that campaign funds from the wealthy are automatically tainted. But it is unrealistic to believe that all Democratic money arrives devoid of any implicit strings. In McAuliffe's world, Democrats never forget their roots: "Listen I don't know what it's like for a rich kid in Kennebunkport but I grew up in a working class family." Schumer too stresses his average-American, Brooklyn upbringing: "My block, East Twenty-Seventh Street, was a mixture of firefighters and cops, salesmen and teachers, small businessmen and homemakers."

Someday, perhaps, mass-based Internet giving may change the class-based structure of political fundraising. But we still live in a world where a Terry McAuliffe (who will be heading up the Hillary Clinton financial juggernaut) has far more sway over Democratic politics than do ideologically committed $100 givers. And that is a major reason why too many politicians (Democrats as well as Republicans) lose sight of the priorities of the middle-class voters Schumer wants to mobilize as a new governing majority.

This story has been corrected since it was first published.

Shares