As you read this, I'm partway across the Atlantic in an oxygenated tin can, both literally and figuratively suspended between America and Europe. I don't expect or deserve any sympathy -- poor me! I just spent three weeks in the South of France! -- but returning from an overseas trip both suntanned and completely exhausted is a strange feeling. Then again, Cannes is a schizophrenic festival, and this year's edition more than most.

Cannes' 60th anniversary year will be remembered as one of the most American-flavored festivals ever. Virtual orgasms of publicity surrounded appearances by Brad Pitt, Angelina Jolie, George Clooney, Quentin Tarantino and Michael Moore (marvelously described by one French journalist as "le prolo-bobo de Flint en Michigan"). On the other hand, if American film is the boy that Cannes goes to bed with after a long night of partying, it's not the boy she takes home to Papa. As the red carpets were being rolled up and the sponsor logos pried off the wall on Sunday night, every major award was given to not merely a non-Hollywood movie, but pretty much an anti-Hollywood movie.

Like every other American who saw Moore's "Sicko" here (with its glowing portrayal of the French standard of living), I was consumed by a more-than-momentary desire to emigrate. The best healthcare system in the world plus marvelous weather, cheap and excellent wine, crusty baguettes every morning and entire supermarket aisles filled with Camembert in differing degrees of ripeness. What's not to like?

Even in a globalized economy, France retains a striking degree of cultural distinctiveness. Most stores still close for a two-and-a-half-hour lunch break, and almost nothing is open on Sunday. Cheap consumer goods from China are scarce. This also means that prices for ordinary consumer goods are startlingly high by American standards, and taxes on high-income wage earners can approach 60 percent. There isn't much dire poverty, thanks to a widespread communitarian ethos, but economic growth is still pretty sluggish. Ethnic tensions and youth unemployment, especially among Arab immigrants and their French-born children, have become the focus of international attention.

Even with the new president, Nicolas Sarkozy, at the helm -- maybe France's most pro-American leader since World War II -- it's not as if the cultural differences will fade all that much. "Spider-Man 3" and the latest "Pirates du Caraïbes" adventure are playing everywhere, but French, Spanish and Italian movies can be found even in small towns, and some American independent films will play more screens in France than they will in the United States. As the anti-globalization protesters used to say, circa Seattle 1999, another world is possible.

"Crazy Love": Behind one of New York's most infamous tabloid crimes, the really weird story

Listen, I'm happy to be heading home, where you can actually find groceries at 4 p.m. on Sunday. How decadent! But I'm not sure Dan Klores' dark and compelling documentary "Crazy Love" (a hit at Sundance last January) should be shown to anybody who's just off the jumbo jet from some other country, except as a tool to convince new immigrants to turn right around and go back to Lesotho or Slovenia, where people behave normally.

Undoubtedly people in other countries have done things as gruesome and disturbing in the name of true romance as the protagonists of "Crazy Love." But Klores (a well-known New York publicist) places his horrifying tale in a fascinating and largely vanished context that is distinctly American, the outer-borough Jewish New York of the 1950s. Formally, his film is a standard-issue documentary, combining period footage with talking-head interviews. But his talking heads are a hoot -- leathery, leisure-suited, foul-mouthed, larger-than-life characters, straight out of the Bronx by way of Palm Beach -- and their story is a Gothic yarn of obsession, crime and forgiveness.

Burt Pugach was a slick, ambulance-chasing lawyer with a fancy car, a wife at home and a string of pretty girlfriends he took to high-end nightclubs. But when he first met Linda Riss, a voluptuous 20-year-old, in the late '50s, he knew she was different. His wiles didn't work on her at first -- she was a practical-minded girl who wanted a husband, not a sugar daddy -- but eventually she succumbed to Burt's flash and cash. When Linda got sick of Burt's empty promises to divorce his wife and dumped him, Burt started to crumble. He stalked her, threatened her, tried to pick fights with her new boyfriend.

If you were alive in New York a half-century ago, you know what came next. If you weren't and you don't, here's your chance to skip ahead to my next item. I'm not sure one can "spoil" a documentary about a widely publicized criminal case, and Klores' movie isn't a whodunit or anything. But some of you are exceedingly sensitive on this subject, so I'm marking time. Dum de dum dum.

Ready? OK, so Pugach finally paid a couple of thugs to come to Riss' house and throw lye in her face when she answered the door. She was mostly blinded and permanently disfigured (and lost all her vision some years later). Pugach defended himself at trial and spun a tissue of lies as long as the Grand Concourse, but was convicted of the assault and went to prison for 14 years (where he played a minor role in the Attica uprising of 1971). And that's where the story really gets weird.

All the while he was in prison, Pugach wrote letters to Linda Riss, who was leading an increasingly depressed and isolated life. Most of them went unanswered. After getting out, Pugach did a live interview with a New York TV news reporter, during which he proposed to Riss on the air. After some back-channel communication -- some of it through a female police officer assigned to protect Riss from Pugach -- she accepted.

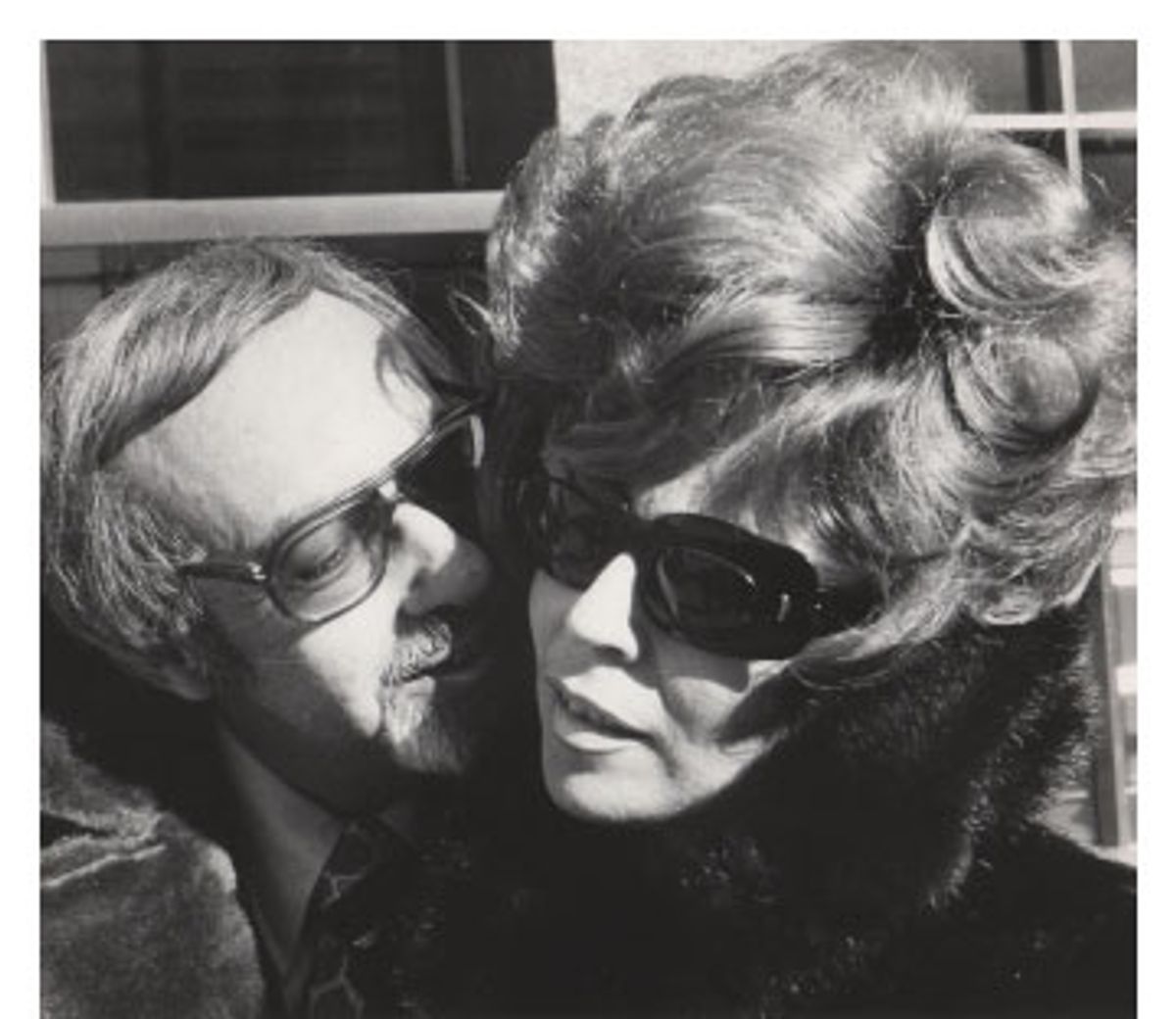

That's right: He had her blinded and she married him. They're still together today, and in "Crazy Love" we see them packing for a cruise-ship vacation, squabbling with each other like Florida Jewish grandparents in a sitcom. She wears ultra-dark glasses, and he has to double-check her clothes for stains or unfastened zippers, but they seem like a normal, irritable older couple with normal older-couple eccentricities. They probably eat dinner at 4:45 and go to the airport four hours early.

There's no justifying what happened or how it happened, and Klores doesn't try. Even some of Linda's friends remain horrified, and if you want to see a parable of evil gender relations in this movie -- the domineering, jealous guy of all time meets the ultimate perma-victim doormat -- it's definitely available. But in depicting the social world out of which this insane marriage came, Klores accomplishes a kind of alchemy that's difficult to verbalize.

I don't think viewers will identify or sympathize with Burt and Linda, exactly -- and I hope if you do, that you'll seek appropriate care. As veteran reporter Jimmy Breslin says in the movie, in 45 years of covering news in New York, he's never met anyone as demonstrably insane as Burt Pugach. Both Pugach and Riss have been down darker roads than most of us ever have to travel, and we should all be grateful for that.

Without excusing Pugach's crime, or explaining Riss' apparent forgiveness, Klores renders them as recognizable human beings, more like the rest of us than like incomprehensible monsters. Amid the horror and contempt, we also feel pity. We've all done bad things to people we loved, or put up with behavior from others when we shouldn't have. Every relationship is a set of secret bargains, with a germ of shared pathology at its core. Burt and Linda's mutual pathology is cranked to a vibration well beyond 11, but most of us can feel the seeds of their madness stirring deep below our own purported sanity.

"Crazy Love" opens June 1 in New York; June 8 in Boston, Chicago, Denver, Los Angeles, Minneapolis, New Haven, Conn., Philadelphia, San Francisco and Washington; June 15 in Atlanta, Baltimore, Dallas, Houston, Miami, Palm Springs, Calif., Salt Lake City, San Diego, Santa Cruz, Calif., Seattle and Austin, Texas; and June 22 in Cleveland, Indianapolis, Nashville, Phoenix, Portland, Ore., Providence, R.I., Rochester, N.Y., Sacramento, Calif., and San Antonio, Texas, with more cities to follow.

"Ten Canoes": From the deep past, an Aussie tale of murder and punishment, plus dick jokes

I didn't catch Australian director Rolf de Heer's "Ten Canoes" last year at Cannes, where it won a special jury prize. Finally acquired by Palm Pictures, it will now trickle out gradually to American screens. This is the first feature film ever made in an Australian aboriginal language -- the language of the Yolngu people, from Arnhem Land in the remote Northern Territory -- and belongs to the semi-anthropological moviemaking tradition of Zacharias Kunuk's "The Fast Runner," an art-house hit in 2002.

Shot in glorious widescreen by cinematographer Ian Jones, "Ten Canoes" offers unforgettable panoramas of the swamps and temperate forests of Arnhem Land, which are entirely different landscapes from the stereotypical Outback deserts so often seen in Australian film. This isn't a movie for the impatient; it includes a story within a story within a story, the outermost one being narrated by legendary aboriginal actor-storyteller David Gulpilil. De Heer's actors, all recruited from the small aboriginal community of Ramingining, are relatively inexpressive by conventional cinema standards, and what plot there is to the film jerks forward in little quantum leaps.

What de Heer, Gulpilil and co-director Peter Djigirr have tried to accomplish is a blending of the discursive, long-winded and allegorical aboriginal storytelling tradition with the 90-minute, three-act structure of movies. I'm not sure "Ten Canoes" is absolutely successful on that front, but it's a fascinating immersion within a highly ritualized Stone Age oral culture that, at least according to tradition, existed almost unchanged for thousands of years before the European arrival.

Gulpilil's story is set during the time of "the ancestors," perhaps a thousand years ago, when a young man named Dayindi (Jamie Gulpilil, son of David) is being taken on his first goose-hunting expedition. His older brother Minygululu (Peter Minygululu) learns that Dayindi covets his third and youngest wife, and decides to tell his own story, designed to discourage adultery. That story goes back even deeper into the past, not long "after the great flood covered the land," and recounts the mythological Cain-and-Abel history of another pair of brothers in which the younger wanted one of the older one's wives.

Got all that? OK, you don't really have to. "Ten Canoes" will hold your interest if you give it time, largely on the basis of that lush and lovely scenery, even if you can't entirely follow the nested narratives or grasp their intended meaning. The innermost tale finally builds up some steam: There's a mysterious stranger, a missing wife, an accidental killing, and a deadly revenge ceremony. There's comic relief in the person of Birrinbirrin (Richard Birrinbirrin), a big-bellied Winnie-the-Pooh type who's always trying to convince others to gather honey for him. (There are even fart jokes, and dick-size jokes.) As in "The Fast Runner," it can be easy to forget that the aboriginal actors in "Ten Canoes" are modern people who drive 4-by-4's and hunt with shotguns; their re-creation of a lifestyle that disappeared more than a century ago feels completely authentic, never forced or sanctimonious.

You have the sense that de Heer is playing to two audiences: first and perhaps foremost, his Ramingining collaborators, who helped create this movie as a kind of community memorial; and secondly, the international film market. It's a balancing act almost as difficult as the traditional Death Dance an aboriginal warrior performed when he knew the end was near. "Ten Canoes" emphasizes both essential human commonality and the distinctive sacred traditions of a long-oppressed culture. As with "The Fast Runner," the individual work may be less important than the new cinematic possibilities it opens.

"Ten Canoes" opens June 1 at Cinema Village in New York, with a national rollout to follow.

Fast forward: Jet-lag timeout

Beyond the Multiplex world HQ will be shuttered next week, as I recover from overdoses of sunscreen, rosé, Romanian cinema and general fabulousness. In the overload of early summer releases, don't miss Marion Cotillard's extraordinary physical performance as French chanteuse Edith Piaf in Olivier Dahan's messy, awkward but often impressive biopic "La Vie en Rose." (In French it's "La Môme," an untranslatable nickname.) Even better is Adrian Shergold's true-life drama "Pierrepoint: The Last Hangman," starring the terrific Timothy Spall as a semi-legendary executioner who sent 450 convicts to their reward in the years before Britain banned the death penalty. Both films will open June 8 in major cities, with wider releases to follow. I'll be back June 14.

Shares