During his rise through Illinois politics, it was inevitable that Barack Obama would encounter a suckerfish like Tony Rezko. Illinois has more governmental bodies than any other state -- over 500 in Cook County alone -- and therefore, more opportunities for operators.

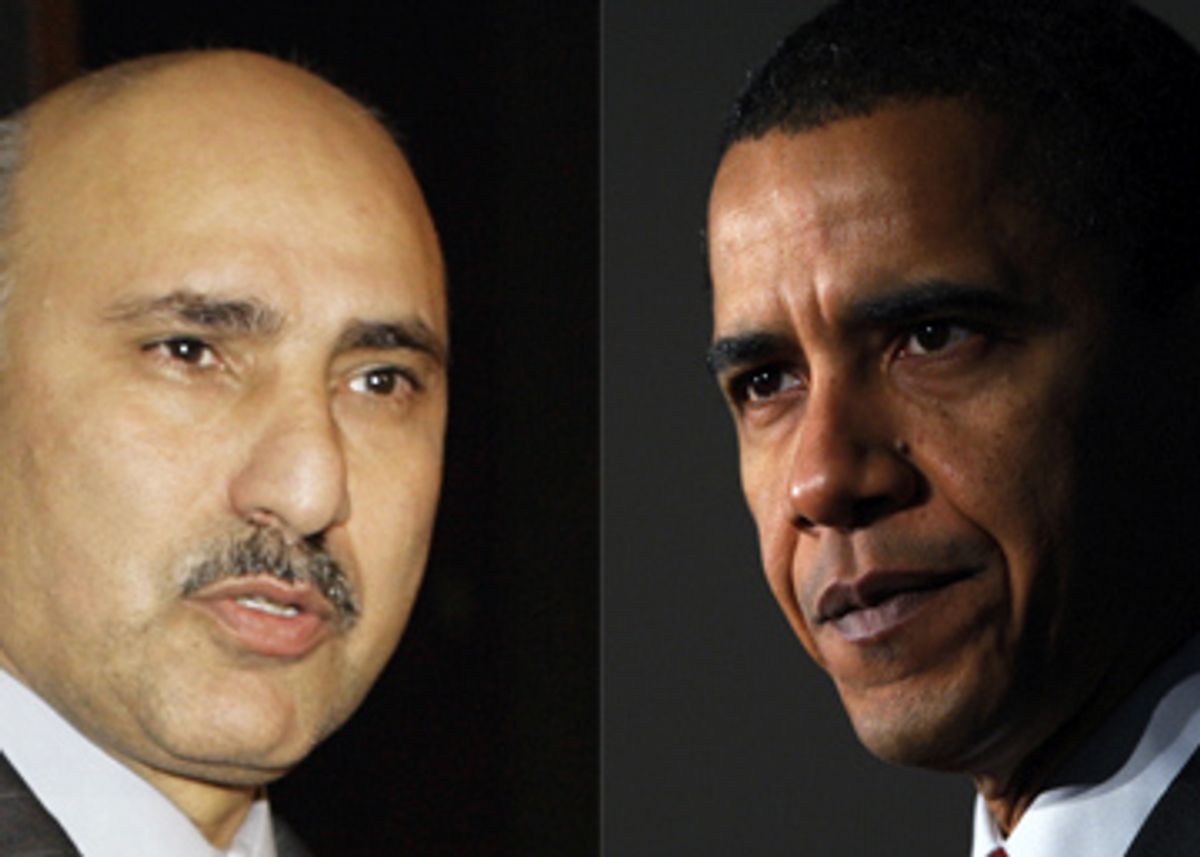

Usually, their antics fill the front pages of only the Chicago Tribune and the Sun-Times. But thanks to an accusation by Hillary Clinton, who called him a "slum landlord," Tony Rezko's alleged crookedness is national news. The Syrian-American businessman is facing federal charges for a scheme to extort money from investment firms seeking business with the state. On Monday, he was arrested at his Mediterranean-style mansion and sent to jail for hiding his assets while out on bond. (Salon attempted to contact Rezko's lawyer, Joseph J. Duffy, but he is "not accepting press calls," according to his office.)

Obama's dealings with his hinky friend have never led him afoul of the law, but they show that, despite his high-minded politics, he was no purer -- or no savvier -- than Illinois' biggest hacks in his weakness for a generous contributor. He wouldn't even say no when Rezko cooked up a deal to help the newly elected senator buy a gracious Georgian-revival home.

Rezko, after all, built part of his fortune by exploiting the black community that Obama had served in the state Senate, and by milking government programs meant to benefit black-owned businesses. But Obama took Rezko's money even after the businessman was sued by the city of Chicago for failing to heat his low-income apartments, and even after Rezko was caught using a black business partner to obtain a minority set-aside for a fast-food franchise at O'Hare Airport.

Now Rezko is wearing an orange jumpsuit. And Obama may spend the rest of the presidential campaign wearing the jacket for his friendship with the fixer.

Antoin "Tony" Rezko arrived in Chicago from Syria in 1971. He barely spoke English, didn't have any relatives on the Cook County Democratic Party's Central Committee, and belonged to an ethnic group -- Arab Christians -- too small to elect even an alderman. There's only one way a guy like that can attain political power. He has to buy it.

Rezko began his career as a civil engineer, but he was soon investing in real estate and fast-food restaurants on the side. Many of his business ventures were in downscale black neighborhoods. He built houses on the historically black South Side, and started chains of Subway sandwich shops and Papa John's pizzerias. Those deals provided him the money to connect with his first powerful patron: Muhammad Ali. In 1983, at the urging of Ali's business manager, Jabir Herbert Muhammad, Rezko held a fundraiser for mayoral candidate Harold Washington, who would become Chicago's first black mayor. After that, he was invited to join Ali's entourage as a business consultant. Rezko put together endorsement deals for the Greatest, and was executive director of the Muhammad Ali Foundation, a group devoted to spreading Islam.

Rezko also used his connections with the Ali camp to expand his fast-food holdings. After Washington was elected mayor, Jabir Herbert Muhammad's company, Crucial Concessions, won a contract to sell food and drinks at the Lake Michigan beaches. Rezko took over the company's operations. In 1997, Crucial opened two Panda Express Restaurants at O'Hare, under the city's minority set-aside program. It was stripped of those franchises in 2005, when investigators determined the company was a front for Rezko.

In 1989, Rezko and a business partner founded Rezmar Inc., a real estate company that aimed to rehabilitate South Side apartment buildings. Partnering with community groups that could help them win government loans, Rezmar purchased 30 properties. At first, Rezmar had a golden reputation. But many of its tenants would have been better off in housing projects. During the winter of 1997, a Rezmar building was without heat for five weeks, until the city took the company to court. It was one of a dozen cases in which the city had to force Rezmar to turn on heat for its tenants. More than half of Rezmar's buildings went into foreclosure, and several have been boarded up. According to a Chicago Sun-Times investigation, Rezmar properties were "riddled with problems -- including squalid living conditions, vacant apartments, lack of heat, squatters and drug dealers."

Rezmar's work was done on the cheap, says a former employee who spoke to Salon on the condition of anonymity. But that was at the urging of the city of Chicago, which figured rehabbers could develop more units if they installed low-grade appliances and cabinetry. When boilers and refrigerators started to wear out after six or seven years, Rezmar hadn't banked enough money to fix them. Rezko's business partner, Daniel Mahru, oversaw the day-to-day maintenance. Rezko's job was to raise equity and cultivate politicians. But that doesn't excuse him from the "slum landlord" tag.

"Somebody pointed out to me that you can't distinguish between [Mahru and Rezko]," the employee says. "They were both responsible." (Mahru did not return a call seeking comment. When Salon called his office a second time to ask about Rezko, a secretary said, "I don't know anything about that," and hung up.)

One of Rezmar's partners was the Woodlawn Preservation and Investment Co. (WPIC), founded by Bishop Arthur Brazier, a prominent South Side pastor who later endorsed Obama in his U.S. Senate campaign. WPIC ended its relationship with Rezmar in 2005, says executive director Laura Lane. The National Equity Fund, which syndicates low-income housing tax credits, tipped off the organization about Rezmar's financial problems. But Lane says Rezmar's properties "weren't in such a state of disrepair." And Brazier disputes the "slum landlord" description.

"When he was with WPIC, the relationship was a good one," he says now.

However, in 2007 Brazier told the Sun-Times that "WPIC became disenchanted with Rezmar and wanted to get rid of them. They thought the buildings weren't being kept up properly. There were some financial problems.''

Obama first met Rezko through Rezmar. In 1990, a Rezmar executive read an article about Obama's election as president of the Harvard Law Review. Intrigued by Obama's interest in housing issues, and his plans to return to Chicago, he phoned the young law student and struck up a friendship. When the executive learned that Obama was interested in politics, he introduced him to Rezko.

"He's great," Rezko told the executive. "He's really going to go places."

After law school, Obama went to work for the firm of Davis Miner Barnhill & Galland. During Rezko's stint in ghetto rehab, Davis Miner represented three community groups in partnership with Rezmar. Through them, the law firm helped Rezko obtain $43 million in government funds.

At last week's debate in South Carolina, Hillary Clinton stung Obama for "representing your contributor, Rezko, in his slum-landlord business in inner-city Chicago."

If Clinton was trying to stick Rezko on Obama, that was the wrong line of attack. At Davis Miner, Obama did a total of five hours of legal work for Rezko, under the supervision of more-experienced attorneys. Obama didn't really become tight with Rezko until he ran for the state Senate, in 1995. Rezko, who can spot a comer, was first in line with a check. The day the campaign started, Obama received $2,000 from two of Rezko's fast-food businesses. Eight years later, when Obama was campaigning for the U.S. Senate, Rezko hosted a fundraiser at his suburban mansion.

Obama's state Senate district contained a number of Rezmar properties, but as a legislator, he couldn't help the company with loans or inspection problems. Still, says Rezko's ex-employee, Rezko appreciated Obama's potential. And hobnobbing with politicians was a sign he'd made it in America.

"Occasionally, he would say to me, 'Can you believe this? You know where I came from,'" says the employee. "He was very humbled by it."

(Around the same time, Rezko was also funding the career of an ambitious young state legislator named Rod Blagojevich, who had been elected to the General Assembly with the help of his ward-boss father-in-law and was aiming for Congress. Over the years, Rezko would donate $117,652 to Blagojevich's campaigns. He was a smart investor in political futures: Blagojevich is now governor. Three of Rezko's associates were appointed to high-ranking positions in Blagojevich's administration. But Rezko's connection to the governor is the source of his current legal troubles: Rezko is going to trial on Feb. 25 on charges he demanded kickbacks from investment firms seeking money from the Illinois Teachers' Retirement Fund. His alleged co-conspirator, who has already pleaded guilty, is Republican fundraiser Stuart Levine. Rezko allegedly used his clout with the Blagojevich administration to help reappoint Levine to the board that controls the fund.)

Rezko was ecumenical in his largesse, doling out hundreds of thousands of dollars in political contributions. He served as an advisor to now-imprisoned Republican Gov. George Ryan, and co-chaired a reelection fundraiser for President George W. Bush. And, of course, he paid to have his photo taken with Bill and Hillary Clinton. (Chicago receiving lines can be so embarrassing: First lady Rosalynn Carter was once photographed with a precinct captain named John Wayne Gacy.)

It's clear that Rezko was always on the lookout for "a clout," Chicagoese for a political patron -- in Rezko's case, a patron who could give a Syrian immigrant the same opportunity to work the system as an Irish lawyer who'd gone to Catholic school with the mayor. In Obama's case, though, Rezko has asked for very little. He's only received one political favor, and it didn't benefit him financially: On Rezko's recommendation, the son of a campaign contributor served an internship in Obama's Senate office. It could be that Rezko was saving his chits until the senator achieved the one office unattainable to a machine pol.

Obama, on the other hand, seems to have derived some material benefit from his friendship with Rezko. During his first year in the Senate, flush with the book advance for "The Audacity of Hope," Obama and his wife decided to trade up from a condo to a bigger, more secure home in Kenwood, a South Side neighborhood of turreted, balconied piles popular with University of Chicago econ professors looking to blow their Nobel Prize loot. They found a $1.65 million house with four fireplaces, a wine cellar and a black wrought-iron fence. The doctor who lived there also owned the vacant lot next door and, although the properties were listed separately, wanted to sell both at the same time. Despite their new income, the Obamas could not have afforded both parcels. The Obamas closed on their house in June 2005. On the same day, Rezko's wife, Rita, purchased the vacant lot for $625,000. They later sold a portion of the lot to the Obamas, for $104,500, so the family could expand its yard. The Rezkos then paid $14,000 to build a fence along the property line.

The sale was brokered by real estate agent Donna Schwan, who'd known Rezko when he lived in the neighborhood. Asked who approached her about the house, Schwan told Salon, "I honestly don't remember. Tony Rezko lived across the street, so he'd been interested in the lot."

Last year, Rezko sold the vacant lot to his attorney, Michael Sreenan, who is now peddling it for $950,000. A "Land for Sale" sign rises above the fenced lot, which is hidden by fir trees. Schwan is handling that deal, too. Since Tuesday, when the property was featured in an NBC report, she's received more than 100 phone calls. Living next door to Obama is a great amenity, she insists. His house is protected by the Secret Service -- their SUVs idle in the street and under the basketball hoop in the driveway. "No Stopping/No Standing" signs bar visitors from parking out front, even though there's a synagogue directly across the street.

"You'd have the most secure house in Chicago," she says.

After the Chicago Tribune uncovered the land deal, Obama described Rezko as "a supporter of mine since my first race for state Senate" and a friend with whom he occasionally had lunch or dinner. Obama knew that Rezko was under grand jury investigation, but believed that "as long as I operated in an open, up-front fashion, and all the T's were crossed and I's were dotted, that it wouldn't be an issue."

James L. Merriner, an Illinois political expert who has conducted the only interview with Rezko since his indictment, says Obama has done "nothing illegal. It's just unsavory."

Obama knew about Rezko's legal problems, but Merriner believes he didn't think they would taint his Senator Galahad image.

"It goes back to when Obama's in the state Senate," Merriner says. "He had a real sense of personal mission. I think he thought he was just above it. He seemed to think he was on a plane above that."

If you've been to Chicago, you know it's a pretty flat place. And if you follow Chicago politics, you know that even the noblest politician can't remain chaste.

"The national media, they tend to overlook that Obama is a regular Cook County Democrat," Merriner says. "Maybe he's a cut above, but he's still an Illinois politician."

As long as Rezko was only under investigation, Obama was willing to do business with him. But then Rezko committed the fixer's biggest sin: He got indicted and got his name in the papers. After that, the friendship cooled. Obama has donated $157,835 in Rezko-linked contributions to charity and has called the real estate deal "boneheaded." But he still lives in the house. And he still has the power Rezko helped him attain.

Shares