It's difficult to tell, from the film "Cool It," whether Bjørn Lomborg enjoys pissing people off, or whether that's just collateral damage. Lomborg is one of those handsome and confident people who draws media attention as a Coleman lantern draws June bugs on a warm spring evening. How well the press has understood the 45-year-old Danish author and researcher, and whether all the exposure has been good for him, is an entirely different matter. Lomborg is a controversial figure in the climate-change conversation -- let's avoid the loaded word "debate" -- but even after sitting through a whole movie about him, I don't feel certain how much of the controversy is his own invention.

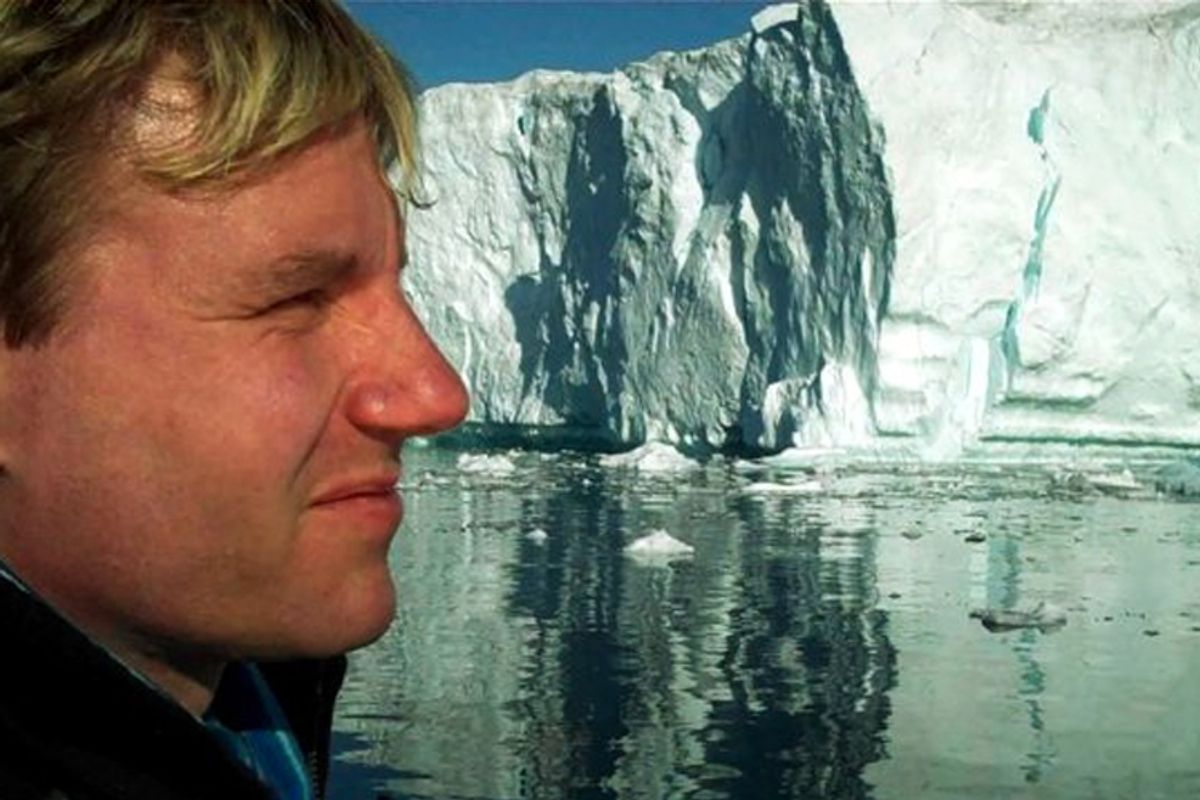

Director Ondi Timoner (who also made the fascinating early-Internet-age documentary "We Live in Public") depicts the buff, blond Lomborg biking to work at his middle-way Copenhagen think tank, where he convenes groups of economists, engineers and scientists and engineering wonks to ponder cost-benefit analyses of how to address virtually every major problem afflicting Planet Earth: malnutrition, sanitation, water, education, housing, healthcare, HIV/AIDS and so on. Oh yeah, including global warming, which Lomborg emphatically says is happening and poses real risks. So why is it that when I brought up Lomborg during a Salon editorial meeting, a co-worker nodded and said, "Oh yeah -- the global-warming skeptic"?

Maybe it's because Lomborg's books, including "The Skeptical Environmentalist" in 2001 and "Cool It: The Skeptical Environmentalist's Guide to Global Warming" (the basis for this film) in 2007, have been "hugely influential in providing cover to politicians, climate-change deniers, and corporations that don't want any part of controls on greenhouse emissions," as Newsweek's Sharon Begley has written. In those books, Lomborg generally reached the conclusion that global warming wasn't nearly as bad as the doomsayers predicted. It was likely to keep on happening no matter what we did, and we were better off spending our money on other priorities and buying some extra galoshes and sunscreen. Lomborg isn't a climate-change denier and never was, but you might say that he plays one on TV, allowing all sorts of nutso right-wingers, creationists, free-marketeers and oil companies to wrap themselves in his quasi-scientific mantle. (Sen. James Inhofe of Oklahoma, a leading denier who has a decent claim on being the craziest person ever elected to national office in the United States, is a big fan.)

I say "quasi-scientific" because Lomborg was trained as a political scientist and statistician, and has no background in the complex array of hard-science disciplines underlining climate-change research. Timoner puts some dribs and drabs in "Cool It" about Lomborg's extensive disputes with the world of mainstream science, but the viewer is likely to come away with the impression that he was fully exonerated of intellectual fraud when the real record is a fair bit murkier than that. John Rennie of Scientific American (which waged an extensive campaign against "The Skeptical Environmentalist") has described Lomborg as "a political scientist who wades into the vastly complex, unsettled literature of environmental science, scrutinizes a fraction of what is to be found there, and emerges confident that the simple summary he has developed is a fair and accurate representation of the science -- notwithstanding the warnings of experts in the disciplines he skims that he is mistaken."

Lomborg has clearly been stung by the suggestion that he's a front man for know-nothingism, and "Cool It" is an agreeable and partly successful attempt to repair his image. His language about global warming has become much less inflammatory in recent years (basically, he now says we do need to do something about it) and the challenge he raises here is probably one worth making. Catastrophist scenarios like Al Gore's "An Inconvenient Truth," he argues, do not lead to good public policy, and international carbon-emissions agreements like the doomed Kyoto Accords run the risk of being extremely expensive while accomplishing next to nothing. I don't have the necessary expertise to deem that true or false, but it's certainly plausible.

In "Cool It" he presents himself as an ideology-free, techno-Utopian facilitator, encouraging engineering breakthroughs that will rescue us from fossil fuels and wackadoodle inventions that will buy us more time. Some of this stuff is ingenious and simple -- paving or painting Los Angeles white instead of black, one scientist suggests, would render it cooler than global warming is likely to make it hotter -- and some of it is strictly from Mars. I adore the pictures of the goofy, humongous, wind-blown "geoengineering" craft that Lomborg hopes will cool the earth by shooting water vapor from the ocean into the sky. They look like Mississippi riverboats out of Mickey Mouse's nightmares. But pigs will fly over the frozen wasteland of hell before we see those things in action.

It's a stimulating and nerdalicious ride, and I came out of it with tremendous admiration for Lomborg's high energy level, appetite for publicity and evidently sincere desire to solve every world problem in one lifetime. (His gym routine is also impressive, from the looks of things.) Optimism and faith in the future are valuable commodities, and Lomborg is right to suggest that we're going to need a lot of them. If his Copenhagen Consensus Center funds, say, the development of an inexpensive fuel cell that will store solar energy efficiently, a lot of people who've said a lot of bad things about him will be eating crow.

But as is so often the case with the techno-Utopian crowd, both Lomborg and Timoner seem virtually unaware of the global economic and political order that is profoundly opposed to breaking the umbilical cord that tethers our civilization to fossil-fuel consumption. The power of multinational energy companies is mentioned only briefly in "Cool It," and the right-wing political renaissance across the Northern Hemisphere, which has been happy to use Lomborg's work for its own purposes, is never mentioned at all. In some perfect, imaginary Adam Smith universe, Lomborg might be right that dispassionate, rational analysis would quickly yield the best solutions for all our problems at the cheapest price. Does he really imagine that we live there?

"Cool It" is now playing in New York, Los Angeles, Boston, Chicago, Dallas, Denver, Houston, Minneapolis, Phoenix, Portland, Ore., Salt Lake City, San Diego, San Francisco, San Jose, Calif., Santa Cruz, Calif., Washington, Seattle and Austin, Texas, with wider national release to follow.

Shares