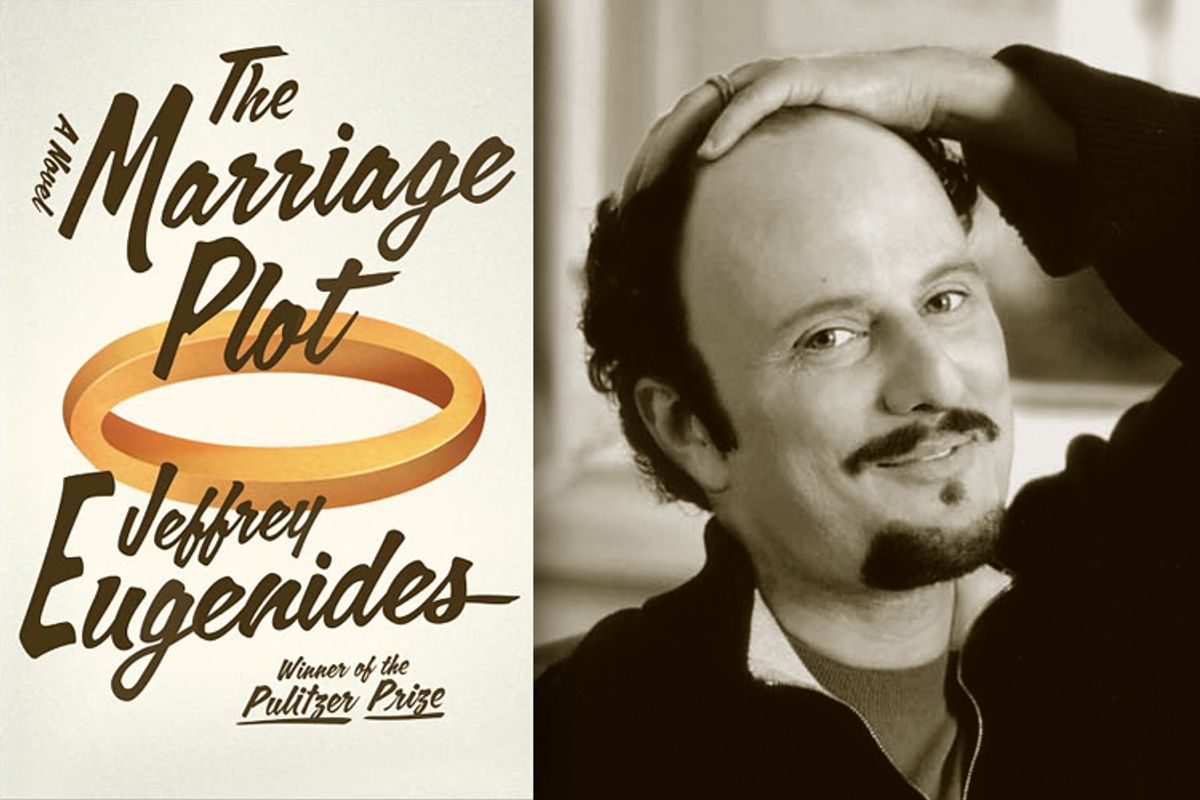

In an early chapter of Jeffrey Eugenides' long-awaited third novel, "The Marriage Plot," one of the three main characters, Brown University undergraduate Madeleine Hanna, seeks relief from the thorny cogitations of her semiotics class by reading Edith Wharton and George Eliot. It's the early 1980s, and such indulgences are under attack. "Reading a novel after reading semiotic theory was like jogging empty-handed after jogging with hand weights," Madeleine thinks. "How wonderful it was when one sentence followed logically from the sentence before! What exquisite guilt she felt, wickedly enjoying narrative!"

Exquisite guilt and wicked enjoyment are more or less what Eugenides intends the readers of "The Marriage Plot" to experience, too. Whether they actually feel guilty or wicked while reading the book will probably depend on how well-developed their intellectual superegos are. If they've convinced themselves that serious literature has to be austere, experimental and a repudiation of the conventional "comforts" of storytelling, then maybe they'll needle themselves for having fun instead of reading a Tom McCarthy or John Banville novel. But who feels guilty about their reading choices anymore (unless, perhaps, it's the Twilight series)?

As for enjoying "The Marriage Plot" -- how could anyone not? It is a headlong, openhearted, shameless embrace (make that a bear hug) of the old-fashioned novel, by which I mean the kind written before 1900. It doesn't present itself as much more than the story of a young woman trying to decide between two suitors, the most attractive of whom is manifestly Not Good For Her -- except for the fact that it is also an elegant argument on behalf of writing novels with just this sort of premise.

The "marriage plot" referred to in Eugenides' title is a term literary theorists use to label novels of courtship; think Jane Austen, Eliot and Anthony Trollope. It's also the subject of Madeleine's thesis, overseen by a dispirited advisor who believes the novel has been on a long downhill slide:

In the days when success in life had depended on marriage, and marriage had depended on money, novelists had had a subject to write about. The great epics sang of war, the novel, of marriage. Sexual equality, good for women, had been bad for the novel. And divorce had undone it completely ... As far as [Professor] Saunders was concerned, marriage didn't mean much anymore, and neither did the novel.

This theory is not uncommon. The critic James Wood invoked it in praising Monica Ali's "Brick Lane" as a book that circumvented the problem by depicting adultery within an immigrant community, where infidelity is still a life-destroying transgression. Because, for most of us, the stakes in choosing a spouse are so much lower today than they were in the 1800s -- when it was an irreversible decision and pretty much the only important choice most women were allowed to make -- deciding whom to marry is no longer seen as a matter of sufficient consequence for a serious novel. A breezy, diverting bit of wish-fulfillment fiction to gobble up on the beach, perhaps, but that's about it.

Whether or not you agree with this notion (and I can't say that I do), Eugenides' full-court-press attempt to prove it wrong is as gloriously sunny, harmonious and rational as a Handel suite. (Reason, according to one of Madeleine's semiotician classmates, is yet another "discredited discourse.") Madeleine falls for her only ally in the class, a brilliant biologist named Leonard Bankhead -- a character obviously, and somewhat distractingly, based on the late David Foster Wallace. This crushes the hopes of her friend Mitchell Grammaticus, who's convinced that Madeleine is the woman he wants to marry.

After they all graduate, Mitchell heads off for Europe and points beyond, embarking on a muddled but earnest spiritual quest that takes him as far as the slums of India. Meanwhile, the balance of power in Madeleine and Leonard's relationship flips when he takes a fellowship at a competitive lab and the severity of his manic-depression emerges. (The lithium he's prescribed makes the experience of sadness resemble "squeezing a baggie full of water and feeling all the properties of the liquid without getting wet.") Social class insinuates itself into the bohemian idyll of college life. Her family is rich, stable and WASPy (even in the depths of heartbreak, Madeleine always keeps her shoes off the coverlet), while Leonard's is broken, chaotic and financially marginal.

The unfolding of this triangle is both a little thing -- just the lives of three interesting and reasonably nice young people -- and capacious enough to contain reflections on what it means to do good and to care for another human being. The resolution feels surprisingly fresh, but best of all, the novel isn't belabored or weighed down by portents of "greatness" -- it lets all that stuff slip from its lovely, golden shoulders on the way to the dance floor. There are certain things that can only be proved if you behave as if you have nothing to prove. Eugenides has just shown the world how that's done.

Shares