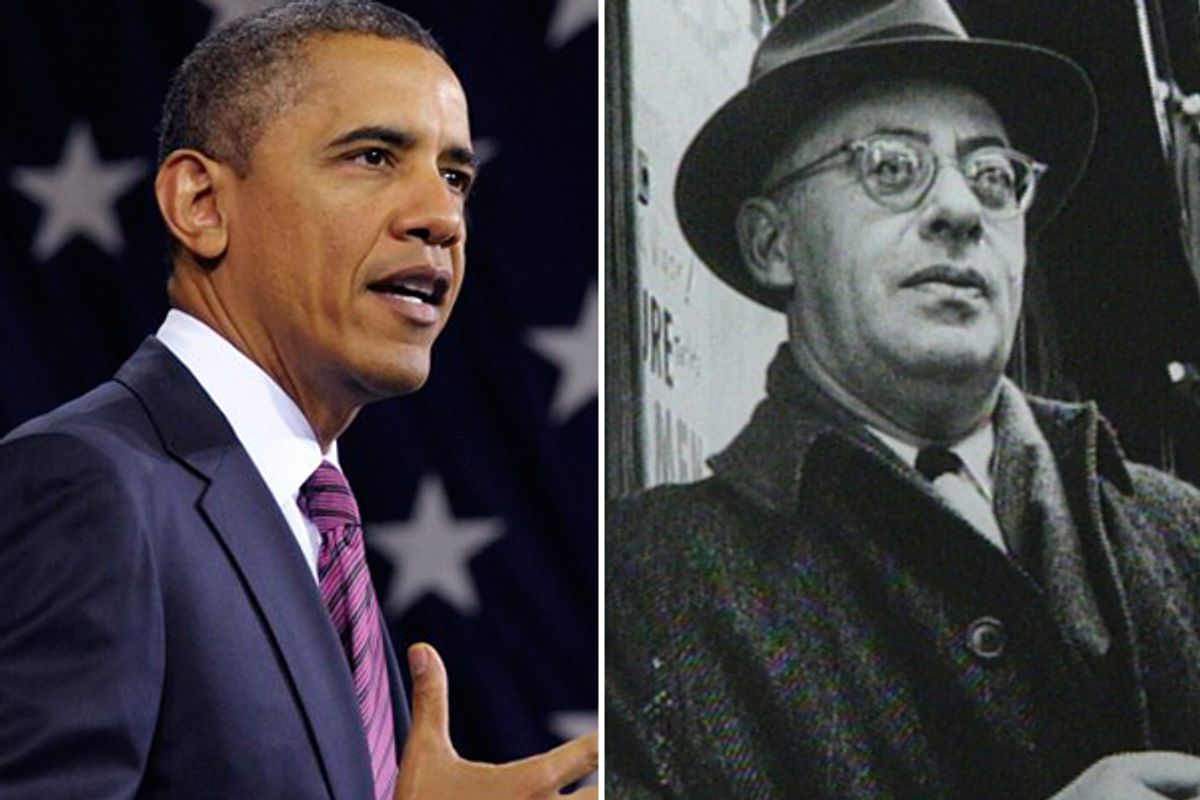

"I am for the Declaration of Independence,” declared Newt Gingrich at a recent campaign appearance, but President Barack Obama “is for the writing of Saul Alinsky. I am for the Constitution; he is for European socialism." Gingrich is not alone in his demonization of Alinsky, widely viewed as the founding father of community organizing. The right's attempt to associate Obama with Alinsky began in earnest during the 2008 campaign, though he was eclipsed for the moment by the Rev. Jeremiah Wright Jr. and Obama’s supposed "pal," '60s radical Bill Ayers. Glenn Beck gave Alinsky prominent billing on his flowchart of conspiracy, drawing arrows connecting him with Obama and the now-defunct ACORN. Rush Limbaugh has labeled both Obama and Alinsky as representative of an elite class of “genuine America-hating radicals.” The Alinsky connection took on even greater salience as right-wing bloggers and pundits sought to delegitimate Obama’s healthcare program as socialistic and his proposed tax reforms as class warfare.

Guilt by association has been a time-honored tactic in American electioneering since the first decade of the Republic, when opponents of Thomas Jefferson tarred him as a bloodthirsty Jacobin, America’s own Robespierre. When Franklin Delano Roosevelt railed against the “economic royalists” and the “moneyed interests” during his 1936 campaign, his critics on the right saw a Bolshevik conspiracy at work. And for Gingrich and Obama’s critics, Alinsky fills the bill: a self-professed radical with a foreign-sounding name posthumously setting the agenda for an ostensibly radical president.

As with all conspiracy theories, the Alinsky-Obama link rests on a kernel of truth. For three years in the mid-1980s, Obama worked for the Developing Communities Project (DCP) of the Calumet Community Religious Conference (CCRC), a group on Chicago’s South Side whose tactics — meeting with displaced steelworkers and marginalized public housing residents -- were inspired by Alinsky. Obama read Alinsky and contributed an essay to a collection of essays on community organizing in Alinsky’s memory published in 1988.

By his own admission, Obama had a rough time being a community organizer. “Sometimes I called a meeting, and nobody showed up,” he recalled. “Sometimes preachers said, ‘Why should I listen to you?’ Sometimes we tried to hold politicians accountable, and they didn’t show up. I couldn’t tell whether I got more out of it than this neighborhood.” By the time he left Chicago for Harvard Law School, Obama was moving down a path that would take him far away from Alinsky-style movement building: He became a civil rights lawyer and law professor and, by the mid-1990s, launched a political career. It is telling that Obama did not mention Alinsky in his memoir, "Dreams From My Father," or in his bestseller, "The Audacity of Hope," though anti-Obama conspiracy theorists would, no doubt, find that silence as evidence of his crypto-Alinskyism.

For his part, Alinsky, who died in 1972, never had much patience for elected officials: Change would not come from top-down leadership, but rather from pressure from below. In his view, politicians took the path of least resistance. Among his targets were the Obamas of his day, from alderman to mayors to senators, for as he wrote in his 1971 bestseller, "Rules for Radicals": “No politician can sit on a hot issue if you make it hot enough.” It’s easy to imagine Alinsky as an advocate for “change we can believe in,” directing the unemployed and the victims of mortgage foreclosures to put pressure on the erstwhile community organizer now in the White House.

Whatever his influence on Obama, Alinsky had a complicated relationship to the political left. In the 1930s, Alinsky had little patience for the bona fide socialists and card-carrying Communists who were prominent advocates of labor and civil rights. He repudiated Marxism then. By the 1960s — his moment of greatest influence — Alinsky was even harsher in his criticism of the New Left. He viewed activists in Students for a Democratic Society as naive and impractical and denounced the tactics of their erstwhile comrades on the militant fringe, like the Black Panthers and the Weather Underground as doomed to failure for their violent tactics and unwillingness to compromise. Alinsky loathed dogmatism of all varieties.

But Alinsky also had little patience for mainstream liberals and European social democrats. He argued that the technocratic style of government by experts and bureaucrats was out of touch with “the people.” Before it became fashionable, he argued for citizen participation in politics and the devolution of power downward, away from Washington and into the hands of ordinary citizens. Though he was a secular Jew, Alinsky forged his closest alliance with Catholic advocates of social justice, whose views at the time could not be described in the easy binary of left versus right. If any political view appealed to Alinsky, it was the Catholic doctrine of “subsidiarity,” namely leaving governance to the smallest possible unit: the community. Alinsky counted among his closest friends the Catholic theologian Jacques Maritain (whose doctrine of personalism was one of the strongest influences on the young Polish cleric Karol Wojtyla, later Pope John Paul II).

Through it all, Alinsky called himself a radical. And he was. Alinsky drew from a deep current of indigenous radicalism in American politics, one that ran from Tom Paine (who was Alinsky’s favorite founding father), through the incipient labor movement (early in his career, Alinsky worked with the Congress of Industrial Organizations), and the civil rights struggle in the 1960s.

In the truest sense of the term, Alinsky was a populist, who sided with those whom he called “the Have-Nots, and the Have-a-Little, Want Mores.” Alinsky’s small-d democracy shaped his strategy. He argued that leaders had to start by listening to ordinary people, not directing them from the top down. In Chicago, Alinsky launched organizing efforts among the ethnic workers in Chicago’s meatpacking plants, whose plight had been made infamous by Upton Sinclair’s "Jungle." In the early 1960s, he launched a campaign to improve the quality of life for the black residents of Chicago’s Woodlawn neighborhood whose housing stock had been gutted by absentee landlords and whose jobs had disappeared because of the corporate search for cheap labor and high profits. And just before his death, he called for a campaign to tap the disaffected lower middle class and turn their anger away from minorities and toward “specific issues -- taxes, jobs, consumer problems, pollution -- and from there move on to the larger issues: pollution in the Pentagon and the Congress and the board rooms of the megacorporations.”

Alinsky believed that the key to organizing success was citizen participation, letting the people set the agenda, not setting it for them. Alinsky’s goal was nothing short of unleashing the power of the people to “create mass organizations to seize power and give it to the people; to realize the democratic dream of equality, justice, peace, cooperation, equal and full opportunities for education, full and useful employment, health, and the creation of those circumstances in which men have the chance to live by the values that give meaning to life.”

It is Alinsky’s populism that is most threatening to Gingrich and the right—even if it is a far cry from Obama’s own political agenda. As political scientist Corey Robin has argued, “[c]onservatism is the theoretical voice of this animus against the agency of the subordinate classes. It provides the most consistent and profound argument for why the lower orders should not be allowed to exercise their independent will, to govern themselves or the polity. Submission is their first duty; agency, the prerogative of elites’ hierarchy.”

Here is the root of the right’s suspicion of Alinsky. His goal was giving the dispossessed agency—empowering them to “fight privilege and power, whether it be inherited or acquired.” In Gingrich’s view, by contrast, the “have nots” are fundamentally incapable, responsible for their own fate because of their immorality, indolence and inertia. They will only be uplifted through the discipline of the market. Put poor elementary school children to work to instill in them a work ethic; cut welfare to promote “personal responsibility,” take away food stamps and reduce unemployment benefits so that the jobless are forced to work. The flip side is a call to augment the power of “job creators” by keeping their capital gains and estate taxes low. In this vision, change comes from above, not from below, and wealth whether inherited or acquired is a social good. Gingrich versus Alinsky is not a battle over ideas; it’s about power, who should have it and who should not. That’s why 40 years after his death, the Chicago radical remains on the right’s enemies list.

Thomas J. Sugrue is author of Not Even Past: Barack Obama and the Burden of Race. He is David Boies Professor of History and Sociology at the University of Pennsylvania.

Shares