A specter was haunting Charlotte over the past week: The specter of Shirley Chisholm, whose historic presidential campaign of 40 years ago was never mentioned (as far as I know) at this year’s Democratic National Convention. Beyond making occasional appearances in rap lyrics -- which she almost certainly never heard -- the church-lady-looking congresswoman from Brooklyn, N.Y., is a nearly forgotten figure in American political history, but one who casts a long and complicated shadow. On one side of the ledger, Chisholm is the unacknowledged grandma of today’s multiracial, multicultural, female-friendly Democratic Party, a direct antecedent to both Barack Obama and Hillary Clinton. On the other side, Chisholm – and her unlikely friendship with segregationist George Wallace -- represents a road not taken, a semi-impossible dream of activist, class-based, cross-racial, coalition politics that might, just might, have produced a much different America than the one we live in today.

Remarkably, there appears to be no scholarly or general-interest biography of Chisholm currently in print. I damn sure hope somebody is writing one. (You can find a reprint of her autobiography, “Unbought and Unbossed,” but that was originally published in 1970, before her presidential campaign.) Her Wikipedia entry is shockingly brief, poorly written and full of mistakes. Filmmaker Shola Lynch’s fine documentary “Chisholm ’72: Unbought & Unbossed” played on PBS in 2005, the year of Chisholm’s death, and went on to win a Peabody Award. But that film, which is available on DVD but not for on-demand or online viewing, remains the only coherent narrative account of Chisholm’s remarkable career and her 1972 campaign. Already the first African-American woman ever elected to Congress, Chisholm in that year became the first black person to run for a major party’s presidential nomination, and only the second woman. (Sen. Margaret Chase Smith of Maine had been a Republican candidate in 1964, running against Barry Goldwater’s Cold War extremism.)

I began to think about Chisholm and her legacy after reminiscing two weeks ago about the memorably dysfunctional 1972 Democratic convention in Miami Beach, where George McGovern gave his acceptance speech at 2:30 a.m. and the atmosphere of long hair, dashikis and patchouli purportedly scared working-class white Americans en masse into voting for Nixon. (Many years later, McGovern himself would quip: “I opened the doors of the Democratic Party, and 20 million people walked out.”) Chisholm received 152 delegate votes at that convention, but many of those were the result of Hubert Humphrey’s decision to release his black delegates to her after it became clear he had lost the nomination. She had won caucuses in Louisiana and Mississippi, but only one primary election, in New Jersey – and that was only possible because neither Humphrey nor McGovern was on the ballot, for procedural reasons.

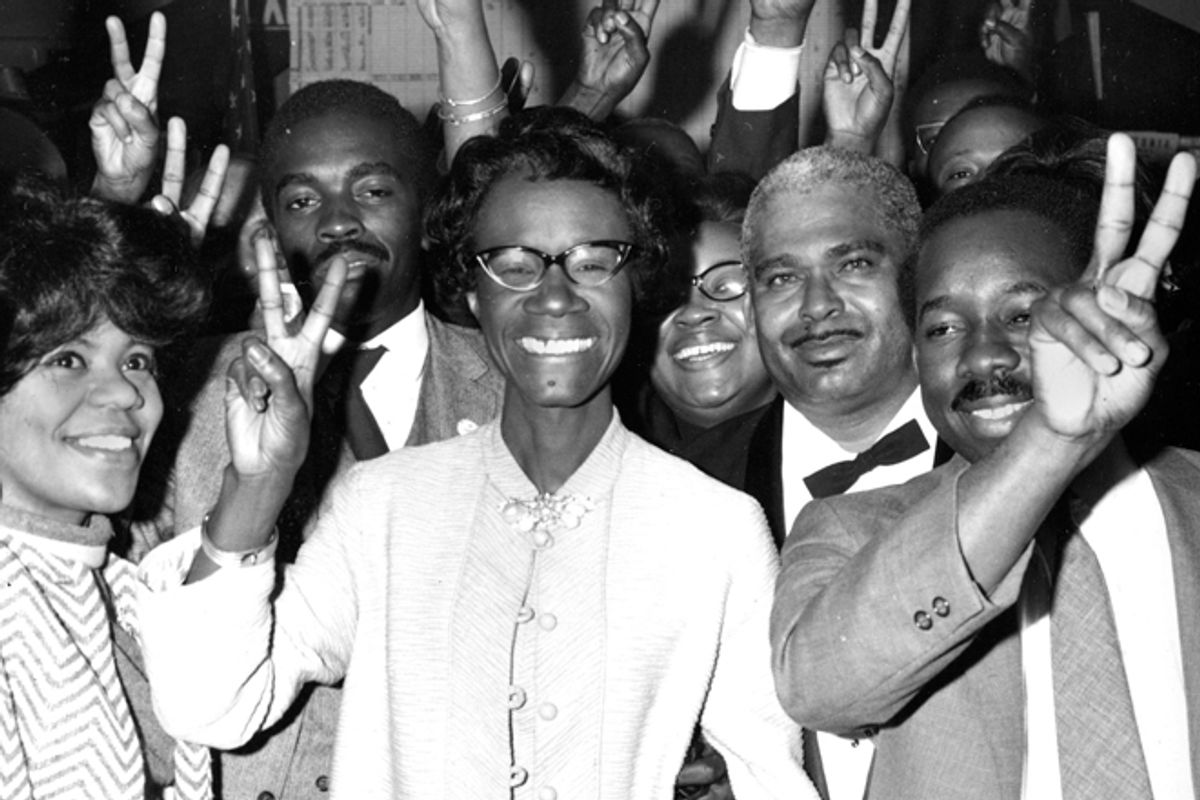

By objective standards, then, Chisholm’s campaign was a failure. But neither she nor anyone else had ever harbored the delusion that she was likely to be elected president, and even as a little kid watching a black-and-white TV from thousands of miles away, I could feel the sense of excitement and history that surrounded Chisholm at that convention. The spindly lady from Bedford-Stuyvesant with weird hair who had been endorsed by Gloria Steinem and the Black Panthers was a ferociously independent figure, most definitely unbought and unbossed. Indeed, old-guard civil rights leaders – most of whom had already pledged allegiance to Humphrey or McGovern or New York mayor John Lindsay -- were taken off guard by her candidacy, with its overtly feminist spin, and thought the whole thing was premature. While it’s probably fair to describe Chisholm as a radical who spoke of reshaping America and of women’s revolutionary role in society, her demeanor was unfailingly ladylike, courteous and dignified.

There’s no known way for me to phone my father in the afterlife and ask him this question, but I have the impression he actually voted for Chisholm in the California primary that year. That may have just been Dad being an ornery Democrat who disliked Humphrey and didn’t quite trust McGovern, or it might have reflected the odd personal consonance between his personal background and Chisholm’s. They had both been born in New York City in the mid-1920s and then sent back to an ancestral island – Barbados in her case, Ireland in my dad’s – to be raised by a grandmother. (Chisholm credited the strict, British-style education she received in Barbados for her adult success, and I know my dad felt the same way about the Latin conjugations and corporal punishment he received from the Christian Brothers.) I also don’t know whether my dad had paid attention to one of the oddest footnotes of that alternate-universe campaign year: an unexpected alliance that had led Alabama’s all-white delegation to cheer Chisholm enthusiastically on the convention floor and many of her black constituents to berate her at town-hall meetings in Brooklyn.

In video interviews conducted late in her life (which you can view in segments on YouTube), Chisholm reflected with bemusement on the unexpected outpouring of Alabamian love, and on the fact that arch-segregationist Alabama Gov. George Wallace, then a leading force in the Democratic Party’s right wing, had repeatedly expressed his admiration for her on the campaign trail. “For some strange, unknown reason, he liked me,” she said. “George Wallace went all over Florida [a state he would win overwhelmingly] and he said to the people, ‘If y’all can’t vote for me, don’t vote for those oval-headed lizards. Vote for Shirley Chisholm!’” (Presumably Wallace was describing his Northern liberal opponents.) Although Chisholm believed that Wallace’s remarks cost her votes in the Sunshine State among blacks who wondered whether she had made a secret covenant with a known racist cracker, she said she didn’t think the Alabama governor had any sinister or strategic intention.

It’s tempting to speculate about this phenomenon, which Chisholm herself said she wished she could understand. Did Wallace identify with Chisholm, on some level, as a political outsider who was sneered at by the Northeastern white establishment? Did he respond to her as a black woman who had good manners and did not raise her voice, and who may have reminded him of proper, churchgoing ladies he’d known growing up in the rural South? Did Chisholm – and this is the most seductive possibility – appeal to the better angels of Wallace’s nature? He had begun his career as a nonracist populist who opposed the Ku Klux Klan, and he would end it as a penitent integrationist. (By 1972, he already claimed to support voluntary integration, although he opposed school busing and his campaign was loaded with racial buzzwords.) But there was that long and dreadful detour in between into the politics of white supremacy, which would provide the Republican Party with a blueprint for Southern conquest.

All that led up to the aftermath of May 15, 1972, when Wallace was shot and gravely injured by a would-be assassin in Maryland, putting him in a wheelchair and essentially ending his national political career. (He would run again in 1976, but made little headway against fellow Southern governor Jimmy Carter.) Chisholm was not the only one of Wallace’s Democratic rivals to visit him in the hospital – Humphrey, Lindsay and Rep. Wilbur Mills also did, at least – but she certainly created the biggest stir. She said later that Wallace was startled to see her and exclaimed, “Shirley Chisholm! What are you doing here?” In an earlier recounting, Chisholm said that Wallace asked her, “What will your people say?” She responded, “I know what they are going to say. But I wouldn’t want what happened to you to happen to anyone.” They held hands, she said, and prayed together while Wallace wept.

It’s not clear in retrospect that Chisholm was operating out of anything but basic human decency. It certainly wasn’t political calculation. As she said much later, “I knew that I was going to be thrown out of office. The people in my district came down on me like anything.” In two rowdy public forums, the one-time schoolteacher lectured her constituents on manners and morals, eventually bringing them around. It’s also not clear that Chisholm felt anywhere near the degree of affection for Wallace he apparently felt for her. But she called on their uneasy friendship one more time, in 1974, when Chisholm sponsored a bill that extended the federal minimum-wage law to domestic workers for the first time, and Wallace worked the phones to Southern congressmen, rounding up enough votes to get it passed. (Did he promise them black votes? Threaten God's judgment? I would love to know.)

I’ll say that again: Shirley Chisholm, the first black woman in Congress, and George Wallace, the most notorious segregationist politician of the 20th century, worked together to raise wages for domestic servants, probably the most abused and unregulated sector of the workforce. (Chisholm’s immigrant mother, in fact, had been a domestic worker, while her father toiled in a factory that made burlap bags.) Was that an unrepeatable one-off event based on a bizarre personal connection, or an example of a cross-racial, North-South, class-based political coalition that might have been? We’ll never know, although it’s tempting to imagine the revolutionary potential of a Chisholm-Wallace ticket – the disabled good ol’ boy and the steely-eyed schoolmarm – which really might have caused the American political universe to explode.

While Chisholm herself is not nearly as famous as she should be – a legacy, perhaps, of the anxiety she provoked among the male-dominated white and black political leadership of the 1970s – her influence runs deep in African-American political life. At least two sitting members of Congress, Rep. Barbara Lee (D-Calif.) and retiring Rep. Edolphus Towns (D-N.Y.), worked for her, as did Democratic National Committee vice chair Donna Brazile. But while Wallace stayed in the Democratic Party and recanted his racist views (which were certainly based on pandering rather than principle), the perennially pissed-off working-class whites he represented are long gone to Nixon and Reagan and the lily-white, Southern-centric current incarnation of the Republican Party. I know it gets old to say that those people are applying a 12-gauge to their own feet, but Wallace told them the truth four decades ago: Shirley Chisholm had their back, much more than the “oval-headed lizards” from Washington with the nice suits and the smooth talk.

As the history of her relationship with Wallace may suggest, Chisholm was more of a realist and pragmatist than anyone could see in 1972, when her campaign was often depicted as a quixotic and destructive crusade likely to split the party. (That happened, all right, but Chisholm was hardly to blame.) She supported white Louisiana congressman Hale Boggs for majority leader over Congressional Black Caucus leader John Conyers, and was rewarded with a prime committee assignment. She refused to back feminist icon Bella Abzug against Daniel Patrick Moynihan in a 1976 New York Senate election, asking “Where was Abzug when I ran for president?” In her autobiography, she writes movingly about the philosophical prison that racism can create for whites, and sexism for men. I think she felt sorry for George Wallace and people like him, long before he got shot, and longed to set him free.

But arguably Shirley Chisholm’s most important decision, and the reason why Democrats and Americans of all races and genders owe her a debt that can never be paid, was her coolly reasoned decision to kick down the door that Barack Obama would stroll through, looking cool about it, 30-odd years later. (Not to mention the one that Hillary Clinton might well enter on her own, a few years hence.) As Chisholm wrote in 1973, "The next time a woman runs, or a black, or a Jew or anyone from a group that the country is ‘not ready’ to elect to its highest office, I believe that he or she will be taken seriously from the start … I ran because somebody had to do it first.”

Shares