David Simon's "Treme," the languorous, exactingly observed, perfectly scored drama set in post-Katrina New Orleans, begins its third season on HBO Sunday. "Treme" has not enjoyed the same fanatical devotion or critical praise as Simon's "The Wire" (though what could), largely because of its willful lack of interest in obeying standard TV plot conventions, unfurling instead at its own idiosyncratic, leisurely pace.

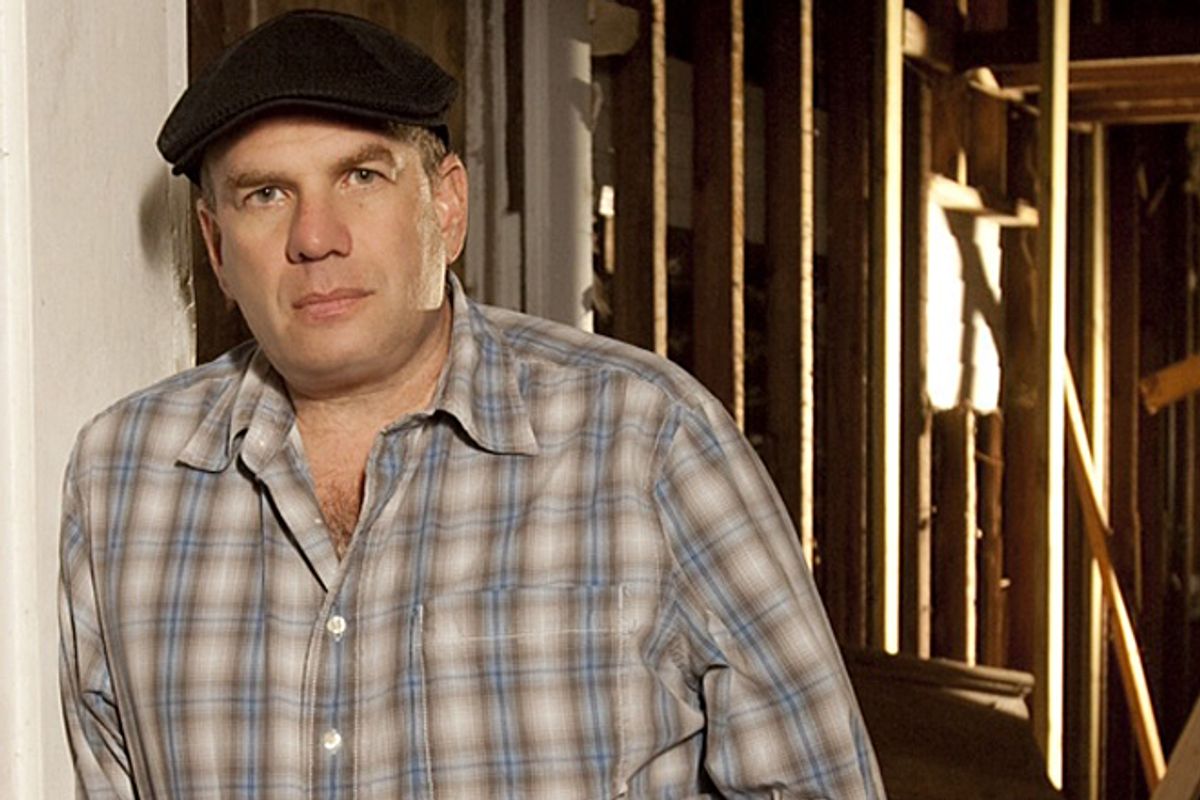

On the occasion of the premiere, Simon, a slow, thoughtful talker, spoke to me about "Treme," his allergy to melodrama, what he makes of most television, and "The Wire" spinoff he wanted to make.

Do you feel like the characters in “Treme” have a capacity for happiness, that maybe the characters on “The Wire” didn't?

They are not quite under as much pressure, I would say. These are not people who are standing on a drug corner with a gun. We very purposefully made a story about post-Katrina New Orleans that utilized ordinary people as characters. Musicians, cooks, a lawyer, a cop, but not people who are engaged in life on a continuously heightened basis. And that was purposeful and we thought that was the best way to tell this particular story. That has its own benefits and it also has its costs. But it’s a choice. If you take ordinary characters, sometimes you’ll end up with ordinary life rather than something hyperbolic and hyper-dramatic. I think there’s a lot of comedy and tragedy and everything in between on display in “Treme.” Happiness? Yeah, maybe.

I think certainly the show is an allegory not just for New Orleans but for where we are as a country. It’s about some people who believed they were part of a communal and societal construct and then found out very abruptly in 2005 that they were on their own. I think in New Orleans, as it turned out, the only thing that worked was the culture. The political landscape was pretty barren of actual leadership. Any promises of economic relief turned out to be disaster capitalism. And all of the social problems that New Orleans had before the storm came right back with a vengeance. So what people had to rely on were each other and what they valued in the experience of city living. We really wanted to explore that, because in a metaphorical sense I think that’s really where the rest of the country is right now. Our flood control system failed three years later, on Wall Street. And we found out, in a way, what New Orleans already knew; in a more literal sense, we found that we’re kind of on our own. And no one’s looking out for us other than us. And is there an “us”? And that’s kind of the question that “Treme" was built to grapple with.

So it makes sense to have ordinary people. I don’t know about you, but I live a pretty ordinary life by most standards. One day to the next is not rooted in hyperbolic tragedy or extraordinary happiness. It’s better than a lot of alternatives. I think that’s what you might be feeling, is that people are living on terms that maybe you recognize as life-size. Because I think the show is life-size. And I think that’s a very vulnerable thing in the medium of television, certainly in American television, and we knew that going in.

Do you still feel like your life is ordinary?

Last weekend I took my kid to college. He’s a freshman, and I was happy to pack the car, and we needed a refrigerator for your allergy shots. And last night it was about getting my daughter to bed on time. And we all want to see the game on Saturday. But 20 blocks away from me people in Baltimore are confronting an entirely different America, and so “The Wire” felt, I think, entirely different. But we weren’t doing a story about the underclass, and we weren’t doing a story about a drug wiretap; we were doing a story about people trying to reconstitute their community. If you don’t show that through the lives of ordinary people you’re kind of cheating. I have very little threshold for melodrama. Probably too low to not get kicked out of television at some point.

“The Wire” is not a genre show, per se, but it was certainly in a conversation with the “cop show” conventions.

Absolutely, we certainly came on the scene with all of the attributes of a cop show and we worked within that format. It wasn’t our intention to make a cop show. But nonetheless, we used some of that.

Do you ever miss that in making a show that has no …

Do I miss doing the same show twice? No, no, no. If I never do a cop show it will be too soon. There are other stories to tell in the world. I didn’t miss “The Wire” when we did “Generation Kill.” If there is a project after “Treme,” and I don’t know that there is, but if there is, I won’t miss “Treme.” The trick is to tell a story that you believe in from beginning to end and execute it as well as you can and then find another story. Do I miss the cop story tropes? Or do I wish we had an emergency room and I could wheel bodies in? Or do I wish it could be “West Wing” and they could be walking in and talking about policy as if they were in charge of everything? No, right now, in the middle of this story, I’m really enjoying writing regular people. And I consider this in some ways the holy grail of television, regular people, people who aren’t gangsters, who aren’t emergency room doctors, who aren’t lawyers arguing a death row case. You don’t see a lot of that on television.

How much do you understand what you’re doing as about being different from other TV?

This sounds really snobbish and I don’t mean it because it’s not like I don’t watch TV, but I find a lot of it to be unwatchable, because I don’t see it as being reflective of anything. It’s not as if we don’t cheat when we make drama. There are cheats in “Treme,” there were certainly cheats in “The Wire.” You’re not trying to make a documentary, you’re not just turning the camera on and letting people be. This is not Frederick Wiseman. But I start seeing those seams where people have sewn together melodrama and they’re not really interested in what the invasion of Iraq at 30 days can tell us or what the years after Katrina in this city that suffered a near-death experience can tell us; what they’re interested in is sustaining a franchise. They’re interested in having a TV show and writing these characters and maximizing the number of eyeballs.

When I start seeing scenes of that, that they don’t care about Iraq or they don’t care about why there’s violence in the inner city, I have no interest in watching. I’d have no interest in reading if that were a novel and it was cheated that much. A lot of TV is about sustaining the franchise. Not all of it. There’s some very good stuff out there. But a lot of it is about sustaining the franchise. You know, looking for the hit. And I’m in the wrong line of work. And the fact that I’ve lasted as long as I have, it’s amusing to nobody more than it is amusing to me. It’s been a delight and it’s been a lot of fun and we’ve gotten to do some things. But believe me I always have one suitcase packed.

What TV do you watch?

Well, I don’t watch 24-hour cable news. I was probably addicted to that stuff five to 10 years ago. It’s gotten so bad, so appallingly bad. I can’t watch any of it. It’s not ideological. I hate MSNBC as much as I hate Fox. I hate the ideological. I hate the transparent disregard for journalism. Now when I’m sort of drawn to it because something’s actually happening in the world, I can’t bear it. The mediocrity. I watch a lot of movies. I love movies. Every now and then you find a gem that you just really love. There was this show called “Slings and Arrows.” Did you see that? Oh my God. That thing was wonderful.

I watched “Luck,” and I thought, like everyone else, I thought, “OK, it’s taking time to establish the world, but far be it for me to criticize David Milch for that.” But I got into that, and I thought he was building a world and he went somewhere with it. And I’m sorry about the horses, but that was good work. It was resonant and it was different and I learned some stuff and I cared about the characters and I cared about what was going to happen. I thought “The Sopranos” was great. I thought “Deadwood” was really intriguing.

I guess I should name some stuff that’s not HBO to be credible. Every now and then I’ll get turned on to a sitcom and I’ll watch a bunch of them and I’ll laugh a lot. And I had an adolescent son for the last five, six years, so give me an episode of “Family Guy,” and it’s Stewie and Brian, I’m fine. Just leave me alone with my son and we’ll laugh our asses off. Again, life is pretty ordinary.

This season, one of the characters, Jeanette, a chef, gets to run a restaurant in New Orleans, but with a business partner who is not ideal. She gets what she wants, but then it’s not really what she wanted.

I think you’ve caught on to something that’s thematic between all the characters, or a lot of the characters, I should say. A lot of characters are trying to figure out — Delmond, for example — what it means to be embraced by the opportunities that present themselves in the world. The money is coming back now. If you can say anything about the continuity of “Treme” it’s that in the first season the people came back. In the second, the problems and the fundamental threat to the city made itself evident again. And in the third season, the money comes back. People saw a lot of opportunities and some people saw a means of changing New Orleans, in ways that they thought might be better. And other people felt threatened by that, and other people felt challenged by that, and other people saw that as opportunity.

And I think that’s very allegorical to the changing economic climate of the country and the way in which capital is rerouting itself, almost before our eyes. Economically there are so many things that are transformational that are going on right now. It’s very close to revolutionary in terms of what kind of society we’re going to be.

So we wanted to put characters at the focal point of that. There ain’t no free in America, as Ed Burns used to say; free is the most expensive thing there is. I think everybody in “Treme” has to find that out. Everything has a cost, everything has a choice. You open one door you have to slam another. People in New Orleans had to make those choices and are still making those choices all the time. Nobody hands you anything with no strings attached. That was really an incredible dynamic that we watched happen in New Orleans. Everything that was conceived of as being better or restorative, ended up being very, very complex and very fraught, not necessarily meaning that all of it was bad or that all of it shouldn’t have happened. Some change is necessary, some change is good and some change is inevitable. But people were tossing a lot of different ways.

One of the things that New Orleans has figured out that the rest of the country has not, is that the past matters. There are things rooted in the past that are the healthiest part of society, of continuity, of community. Everything is tradition in New Orleans. New traditions are acquired, it’s not a museum piece, and some traditions fall away, but everything is thought about. Everything is recollected, everything is argued over. Who makes the best gumbo? It’s an argument — the only correct answer of which is my mama. This is the only reservoir of strength that that city has.

Face it, that city has the worst urban police department in America, by far. That’s empirical. There is no place in America that — it’s under a federal court order now — that has had as many actual federal prosecutions against its members as New Orleans. The school system was a disaster before the storm. Now its a balkanized nightmare, where some schools have actually improved and others are without a light bulb. The government is one of the most hopelessly, hilariously corrupt in the history of the republic, local government down there. Not a lot works in New Orleans. The infrastructure is … never mind flood control, the potholes there. We had a 3-foot sinkhole at the end of the street where I lived, and the city finally put an orange and white barrel in it. And four months later nothing had happened, so finally for Mardi Gras, the neighbors did something very clever, they decorated it, they gave it beads and it had a funny little hat, and it looked great. And yet people will not live anywhere else than New Orleans. Why? Why is there such city-state patriotism to this place? Because there’s no other place like it. Because there’s a search for itself every day, culturally. In terms of how people eat, how they dance, how they sing, how they make music, how they walk down the street, how they parade. Everything is asserted for culturally that can possibly be asserted for.

To me, there’s a message in there for what still matters. Why does it matter that we’re Americans? Are we the greatest country in the world? Not quite so sure. We’re certainly not the country we were. And there’s a lot that doesn’t make me particularly proud to be an America. But watching New Orleans come back here after the storm I feel intensely American and intensely proud. And it has nothing to do with policy. The people who are doing this, asserting for culture, aren’t doing so within a kind of political mission. They’re not even thinking politically, they’re just going through their day. And their day requires them to be here in New Orleans and not be in D.C. or Baton Rouge or anywhere else. There’s something I’m finding very meaningful in writing this story. And in some ways it’s bringing me into a real discussion with myself about what it means to be an American and why it matters that we’re Americans.

Was your experience working on “The Wire” an angrier conversation with America?

You can’t help being angry about a lot of stuff that happened in New Orleans and is still happening. And there was a lot of affection for the characters in “Generation Kill” and “The Wire.” The only difference is that … I come from a world of prose. I wrote long narratives that were about certain things. I wrote a book called “Homicide.” That was about police work. And about what it was to do that job, trying to catch the right guy who did the wrong thing. And then the next book I did was about what it felt like to be policed under the auspices of a drug prohibition, in a neighborhood that had been devoured by that prohibition. And the two books were different journeys. The books had different purposes. And one didn’t invalidate the other in my mind. But the idea that I was going to finish “Homicide” and then do another book about police, no. I put everything I had into one and then it was time to tell a new story about a new situation, a new dynamic, a new dialectic. I feel the same way about the TV projects. I liked the cops when we wrote the cops. I liked the drug dealers when we wrote the drug dealers. I liked the recon Marines when we wrote them.

You sound like you’re surprised that people are still surprised that you’re not doing the same thing as “The Wire.”

Who would go back? The number of people who looked upon this show and were expecting the rhythms and the payoffs to be the same as “The Wire,” I expected that. You can’t be naive about what you’ve done before and what people are expecting. But I thought the interim piece of “Generation Kill” might at least say, “We’re after something different.” If you tell the same story twice or three times, you’re a hack. And not only that you’re bored. It’s diminishing returns. You’ve said what you have to say. The world is full of stories.

Like right now I’m fighting like hell to get a fourth season. Why? Not to sustain the franchise, but to finish the story, because stories have a beginning, middle and end. And I’m in the same place as I was with “The Wire.” We’re just begging to finish the story, which I had to do for the last two years. Nothing changes. HBO is, by standards of a television network, incredibly indulgent of this kind of storytelling. But by the standards of a publishing house, which is where I come from, nobody in publishing says, “We really liked those eight chapters, but we’re not going to publish the last eight, so start another book.” No, you finish the book and you put it out there. Then you move onto another book. That’s the world I come from. I find it increasingly exhausting to live in this world. Which is my own fault, I guess, for being in the wrong profession. I’m not blaming anybody. Nor do I want to go five seasons or six seasons, or just have “Treme” up just to have it up. At that point I’m damaging the piece. But do I want to get to 2008 and the financial collapse of the country? And do I want to get to the new administration for reasons that are actually key to what happened on the ground in New Orleans? Absolutely. Without them there’s no point in writing three quarters of a book.

“The Wire” became a phenomenon later in its run...

Season 4. By the way, the numbers went down every year. The critics couldn’t stop kvelling, to use a Yiddish word. Season 4 we were golden with the critics. We got very good reviews with a significant number of critics by the end of Season 1. I’m not going to argue that we didn’t always have the critics. By the end of Season 4 the critics were aggressively trumpeting the show, but the ratings went down from Season 2 on. They bumped up when we had white people on for Season 2. Sorry, [then head of HBO original programming] Chris Albrecht, but that wasn’t the plan. The vast majority of people did not find the show until it was off the air.

So as you’re making “Treme” now, a show that hasn’t been championed as strongly, does that feel different?

Certainly the critics can help. Certainly smart criticism not only can help boost the show but sometimes it makes the show better. Particularly if someone is summarizing a season after the fact. I’m less enamored of stuff where people recount an episode and blog it that way, when you’re sort of making judgments about the show in advance. I have trouble saying this, I don’t know why it’s so controversial, but obviously people know after they’ve acquired something that’s a story, what the story did or didn’t achieve, how well it was or wasn’t executed. A lot of that criticism can be very good feedback for anybody who’s in the business of telling a story.

But “The Wire” got sold by word of month. And that matters as much or more than criticism in the moment. And I didn’t get that. It’s not like we had a plan with “The Wire,” but I now believe in it. Take “Generation Kill,” which came and went with fairly decent reviews, but got clobbered in the New Yorker, for example. And I’ll tell you now, that’s probably the best-executed seven hours of television I’ve ever been involved. Better than “The Wire.” Better than “Treme.” Not in terms of the value of the piece. But in terms of, this is what we’re trying to do, this is what is important to convey, these are real people, we’re going to use the real names of the real Marines, we’re only going to stick to what happened, and then tell the story as best as you can. For the time and the money we put into that, I don’t think I could be prouder of anything.

But most people at the point “Generation Kill” came out — that was right after Fallujah and a lot of the casualties in the war — and most Americans had opted out of that war emotionally. So nobody watched it. If I gave you the quiet DVD sales on “Generation Kill,” it’s selling more DVDs now, five years after it's been on the air. If you go on Twitter, and look at hashmark “Generation Kill,” you’ll find a community that’s obsessed with it in the same sort of “Wire” way. It doesn’t have 60 hours behind it. It’s not “The Wire” in terms of product, but in terms of people finding it, they’re finding it now.

I’ve come to believe that — and people in HBO may not believe this — but what I’ve come to believe is that nothing good happens unless you tell the story you intended and you put it out there. Television is more of a lending library than appointment television now, because box sets exist and because HBO has gone all in on subscriptions. You subscribe, here’s 2,000 hours of programming. If that’s the way television really is, the show will find its audience, “Treme” will find its audience, if it’s completed. If it tells the story it intends on telling and if we’ve executed well enough. If not, nothing else matters.

“The Wire” was supposed to be canceled; in fact it was cancelled after three seasons. And I went in and I wrapped my arms around Chris Albrecht’s legs and begged. And to his great credit, he listened to the story and he said OK. And then I begged again after Season 4, and to his great credit he said OK again. But I don’t believe anymore that I’m capable of making a television show or being involved in a television show that people come to right away and say, “Did you see last night’s episode? That was so fucking great. “ I don’t have the DNA for it. If I had that skill set I would have demonstrated it a long time ago.

But that’s not true! During the last season of “The Wire” I had people saying that to me all the time.

Maybe. We only have certain ways of being able to gauge it. What comes back to you comes back to you and what doesn’t doesn’t. But one solid metric of when people are finding something is they send me the sales figures every six months for the DVDs. And “The Wire” started selling DVDs hand over fist in 2010, 2011. It was off the air. And “Generation Kill” now is going up. Why would “Generation Kill,” utterly unheralded and untalked about by mainstream media after its initial release, why would it be selling twice as many DVDs now in 2012 as when the DVD box sets came out? That’s just word of mouth. That’s just guys at Camp Pendelton in the Marines for two years telling their families, their brother, whoever else, “You’ve just got to see this miniseries. Because these guys got what we do. That’s how we talk.”

That was real enough to sustain it by word-of-mouth. I have to believe in the story, and that the way in which we execute matters. And I can’t take my eyes off that and try to aim the ball. Bad baseball metaphor, but whenever a pitcher starts to aim the ball, he can’t throw a strike. He’s just got to just get out there and throw. You’ve got to believe in the story and the reasons that you’re telling the story are true to what you’re trying to convey. We could have made “Generation Kill” a lot more exciting. But what we really wanted it to show was what does it mean for young men to go to war. In truth. Not in some Hollywood version of it. What does it mean? What does modern warfare mean to the human spirit? What really happened to these young men that we sent there?

In an earlier interview you did with Salon, you said it was your job to be entertaining, but I think that might mean something different to you than most people.

I guess so. It’s not my job to titillate. I’m not trying to manipulate the viewer on a moment-by-moment basis. We all know when that happens, we all know the gratifications involved, but what I’m more interested in is how do you feel about a story I told five years after I told it. Is this thing gonna stand? A lot of stories get told well. But they slip below the surface of the water and you never hear about them again. A lot of that can’t be controlled, it’s not like a formula. But nothing can go right unless it means something. Unless it’s about something, unless it's making some sort of cogent thematic argument.

I started writing to be a reporter. When I got a good story I didn’t want it up so that you’d be excited at every other paragraph, I wanted you to get to the end. I knew I had to write a story that was interesting enough to get you to the end. What I’m really looking for is the guy to put the newspaper down, and turn to his wife or his kid or his co-worker and say, “Did you read this thing in the paper? Do you believe that’s going on?” And the moment afterward, when he puts the paper down, that’s the moment you’re always writing for as a reporter. Same now. I’m not trying to bring the maximum number of eyeballs because I’m not good at that. I’m really not. The world isn’t exactly beating a path, like I gotta get in business with that Simon guy, because I really need to be getting shitty ass ratings, and be hearing from a guy who is insistent that he needs 12 more episodes to finish.

It’s a very funny story, but at some point after Season 3 of “The Wire,” and we introduced the political in Season 3, we wrote a spinoff show for city hall. We actually went to Chris Albrecht and said, “Here’s a pilot of a show called 'The Hall' that follows the Carcetti character and his political career. And we want to run them in tandem.” So after Season 3 of “The Wire” you would get Season 1 of “The Hall,” then you’d get Season 4 of “The Wire,” then Season 2 of “The Hall.” This poor guy must have been listening to this and saying, “Yeah that’s what I need, I need two shows that nobody’s watching in Baltimore, Maryland. What the ...” He had to be laughing his ass off inside.

But if you ask me that would have been an incredible political show, watching Carcetti even more intimately than we were able to portray him within the show, watching that guy maneuver toward the governorship and maybe beyond. That would have been an incredible journey through what politics actually is. Not "Father Knows Best" politics, but actual politics. I reached out to some of the better political writers, and they were like, “Yeah, if you can get that, I’m on.” I was already constructing a writing staff. I walked into this office in L.A., and Chris must have been looking at me like, “Dude, I’m trying to figure out how to cancel the one show!” I have great affection for how much tolerance HBO has shown me thus far. But what I do doesn’t work, it will never work, without that tolerance.

Shares