Whoever the gay equivalent of Jackie Robinson will be – and according to some sources, we may get several of them at the same time – he (or they) is almost certainly already playing professional sports, and may well be an established star. Robinson’s history-making Major League Baseball debut in 1947 was enormously dramatic, of course, but lacked that level of shadowy intrigue: No one wondered whether Stan Musial or Ted Williams might abruptly announce that he’d been black the whole time, like the tormented hero of a Faulkner novel. (Although, given the bizarre history of race in America, who really knows? There were a handful of earlier cases when baseball teams tried to “pass” light-skinned African-American players as Native Americans – and that’s a terrific movie idea if I’ve ever heard one.)

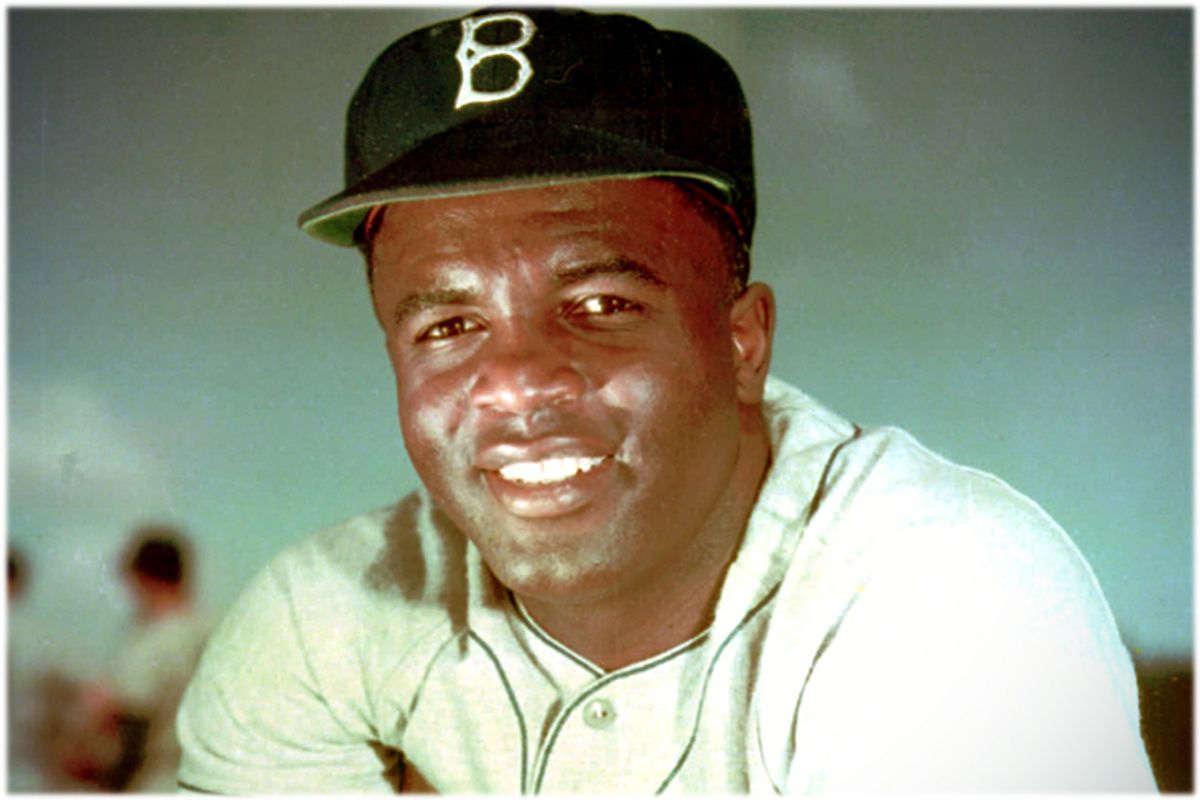

Furthermore, as Salon’s Katie McDonough reported on Friday, sports-marketing experts expect the first out gay athlete in a major North American male team sport to reap enormous benefits, in the form of lucrative endorsement deals and a tide of largely positive publicity. No such opportunities existed for Robinson in 1947, when the Brooklyn Dodgers paid him $600 a month -- a reasonable middle-class salary at the time, but nothing more. Will that first out gay star also receive hate mail from bigots, and face locker-room snickering and on-field slurs, as Robinson did? Almost certainly – but the bigots will also understand that they need to keep their hatred on the down-low, and that they’re already on the losing side of history.

So the differences between the two situations are more striking than the similarities, although you can identify some of both. When he put Robinson on the field 66 baseball seasons ago, Brooklyn Dodgers president Branch Rickey enlisted his sport on the front lines of America’s postwar struggle with its conscience. As we see in writer-director Brian Helgeland’s sanitized and dull Hollywood hagiography “42,” this week’s biggest movie release, Rickey (played by Harrison Ford with growly, hirsute vigor) was trying to do well by doing good, in the great American tradition. Rickey had played with African-American teammates as a young man, and was a devout Methodist who opposed baseball’s unwritten “color bar” on moral grounds. Just as important, he saw tremendous untapped potential in baseball’s Negro Leagues; the first major-league team to integrate its roster would have an immediate competitive advantage, and would see a huge influx of African-American fans at the turnstiles. (Indeed, for Robinson's first game in Brooklyn the crowd of 26,000 was at least half black people.)

What “42” glosses over, as Peter Dreier explains in the Atlantic, is that Robinson’s baseball breakthrough was not simply a matter of individual heroism – although Robinson and Rickey are genuine heroes, make no mistake -- and that it didn’t come out of nowhere. Beginning in the 1930s, the black press, the progressive quadrant of the union movement and a number of left-leaning political leaders had specifically targeted baseball’s color bar, which dated to the 19th century, as a potent symbol of discrimination. There were demonstrations at the 1940 World’s Fair, and outside ballparks in New York and Chicago. New York City councilman Ben Davis, who represented Harlem, passed out an explosive campaign leaflet that featured photos of two black men, one a soldier lying dead on the battlefield and the other a ballplayer in uniform: “Good enough to die for his country, but not good enough for organized baseball.”

But Davis, like many people in the activist wing of the American left in those years – and many people involved in the struggle to integrate baseball -- was a member of the Communist Party, an association that baseball’s leadership treated like a double dose of syphilis with cholera on top. (Dreier recounts that when known Communist Paul Robeson spoke against the color bar at the 1943 winter meeting of baseball owners, they pointedly ignored him.) As with the case of Rosa Parks and the Montgomery, Ala., bus boycott a few years later, the Jackie Robinson story emerged from long-term concerted social action and was turned after the fact, in the mythological retelling, into a story of plucky American individualism. (Until I was an adult, I believed that Parks was just a Montgomery lady with tired feet who decided, on the spur of the moment, that she'd had enough.)

In drawing a parallel with the current situation for gay athletes, my point is that it’s no use trying to disentangle Branch Rickey’s more cynical motives from his altruistic social impulses. As pioneering sociologist Max Weber observed in 1905 – Branch Rickey’s first season as a big-league catcher, with the St. Louis Browns – the two strands are profoundly intertwined in the history of capitalism. However you slice it, Rickey and Robinson crawled out on a limb together, integrating the national pastime nearly a full decade before the Civil Rights Movement began to pose a serious challenge to Jim Crow. While the analogy is imprecise, it’s almost as if the first gay baseball or football player had come out shortly after Harvey Milk’s election, or at any rate before the 1993 March on Washington.

In 2013, the four major North American pro sports leagues find themselves in a very different position. They’re struggling to catch up to a rapidly changing society that in many ways has moved past their insular and anachronistic culture of machismo. No one disputes that there have been gay athletes in pro sports for decades; it’s just that they stayed in the closet while they were still playing (and, in most cases, after that too). When former NFL running back Dave Kopay came out in the mid-1970s – the first prominent American team-sport athlete to do so -- there was widespread speculation that active players would soon follow. There are numerous reasons why that didn’t happen, including the Anita Bryant anti-gay backlash of the late ‘70s and the subsequent emergence of the HIV epidemic, which fueled a noxious tide of homophobia. Among the millions of Americans who died of AIDS were former NFL tight end Jerry Smith and former major-league outfielder Glenn Burke, neither of whom came out during his lifetime.

In an America where a majority of citizens now apparently support same-sex marriage, and where opponents of LGBT rights find themselves increasingly on the defensive, the team-sports locker room has remained a fortress of traditional masculinity, fueled by fundamentalist Christianity, unquestioning patriotism and other “heartland values.” But the definition of traditional masculinity is also shifting, if perhaps not as quickly as the overall society. When straight athletes who support LGBT causes, like the NFL players Brendon Ayanbadejo and Chris Kluwe, began to speak out, it took many in and around the sports world by surprise. There was certainly some initial pushback, including Maryland state legislator Emmett C. Burns Jr.’s letter last season to the Baltimore Ravens, Ayanbadejo’s team, urging them to shut him up.

Burns is an African-American who was 6 years old when Jackie Robinson took the field in Brooklyn for the first time. If he had reflected more deeply on that history, or simply had a chance to see “42,” he might have thought twice about that letter, which cast him temporarily in the villain role played by Philadelphia Phillies manager Ben Chapman in 1947. While Helgeland’s film tumbles into nearly all the pitfalls of historical filmmaking (boring and simplistic) and baseball movies (treacly and unconvincing), it depicts the Chapman incident accurately. By insistently heckling Robinson with racist abuse, urging him to go back to the cotton fields and ordering Phillies pitchers to bean him whenever possible, Chapman only succeeded in driving public opinion, and a great many previously skeptical white ballplayers, into Robinson’s corner. I’m not suggesting that Burns’ letter to the Ravens expressed the same vicious hatred, but it asked the same question: Do you really want to stand with unreasoning prejudice, when all the other side asks for is basic fairness and decency?

Just as we can assume that Kluwe and Ayanbadejo are not the only straight athletes who have knowingly shared a locker room with gay teammates and found it no huge deal, many of baseball’s biggest white stars played with or against black men during the segregated era, often in post-season barnstorming tours or visits to Latin America and the Caribbean. Babe Ruth, the most revered player in baseball history, played many such games against black teams, often socializing with African-American players and fans after the game. Most white players weren't as friendly as Ruth, but many of them understood that there were numerous Negro League players good enough to compete for their jobs. One thing that comes through clearly enough in "42" is that the color bar served as a form of protectionism for mediocre white ballplayers.

The film's biggest problem is that its supposed hero (played with handsome stolidity by Chadwick Boseman) is an essentially undramatic figure, a cardboard secular saint nearly free of personality or internal conflict. If Spike Lee had directed the movie instead of Helgeland, it might have ended up better or worse, but it wouldn't have made Jackie Robinson himself seem so boring. He cuts through the story like a dignified ship’s figurehead, barely changing expression; the real drama of “42” is not about anything Robinson says or does but how white people react to him. Certainly that’s part of the story: Rickey and Chapman's roles can’t be overlooked, and Dodger shortstop Pee Wee Reese (Lucas Black), a good ol’ boy from segregated Kentucky, created a sensation – not to mention a photo-op for the ages -- when he threw his arm around Robinson’s shoulders in front of a hostile crowd at Cincinnati's Crosley Field.

I got caught up in the story of “42” despite myself, but this creaky, old-school Hollywood crowd-pleaser sells the real Robinson short in all kinds of ways. He almost certainly wasn’t the best ballplayer in the Negro Leagues – that would have been Josh Gibson, who died heartbroken after being passed over – but Dickey picked Robinson because his highly unusual background suggested he was well suited to withstand the abuse they both knew was coming. Robinson grew up in the predominantly white surroundings of Pasadena, Calif., had lettered in four sports at UCLA and served as an Army lieutenant during World War II, at a time when there were very few black officers. He was probably better educated, more worldly and more upwardly mobile than any of his Dodger teammates, who were mostly small-town boys from the rural South or Midwest or the sons of immigrants. He belonged to the largely white Methodist church (like Rickey), and although he spent his later career as an African-American activist he was a political moderate who campaigned for Richard Nixon in 1960. (He lived long enough to regret that one.)

Don’t be surprised if the first openly gay NFL or NBA or MLB player fits the red-white-and-blue, all-American boy profile pretty closely too. Can they really find a buff Christian linebacker who voted for Mitt Romney and is all set to marry his long-term boyfriend? If you even have to ask that question, you're no true American. Recent comments by Brendon Ayanbadejo suggest that the coming-out party in the NFL, whenever it happens, may involve as many as four players, and will be one of the most carefully coordinated product rollouts since the iPad. As with Jackie Robinson in 1947, it will represent many years of organized and fearless social activism, most of which will get swept under the rug in the books written for kids 20 years from now. I only hope it produces a better movie.

Shares