Like a state covered by a range of microclimates, the culture world is a baffling and contradictory place these days. The last decade or so has been a rough time for much of the creative class -- with a bad economy, the disruptions of digital technology, piracy from every direction -- and for cultural institutions in particular. The record industry has been fraying since Napster; independent film studios have shuttered as noisy sequels swallow the movie world. Radio has gone from bad to worse in the age of Clear Channel. Bookstores are being destroyed by Amazon. Reporters and critics and photographers continue to lose their jobs. And much of what’s selling big is worse than it’s ever been.

The long-tail, "culture wants to be free" crowd told us the decentralized 21st century would make culture rich, complex, eclectic. The breaking up of the mainstream into a series of niches, however, has not produced a great flowering. Of course, as cold winters can surprise everyone during an era of global warming, there are exceptions: In some fields actual quality has become one of those viable niches.

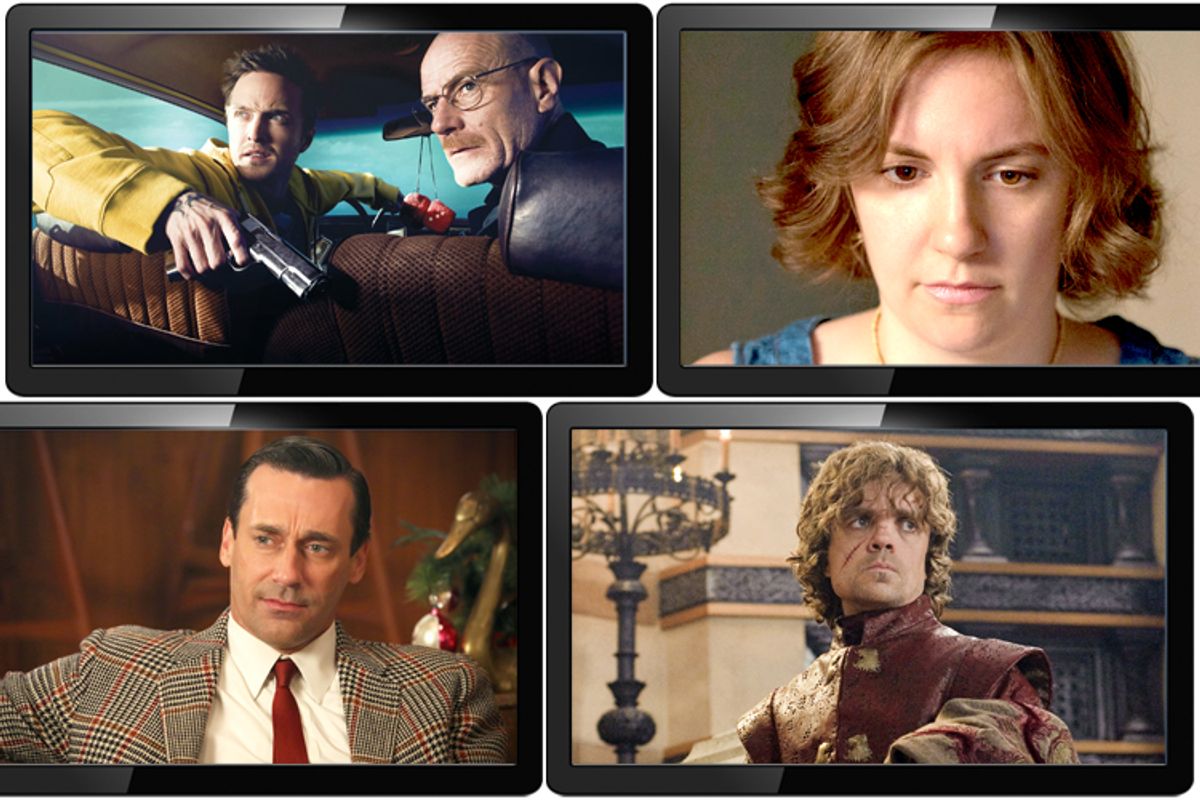

The rise of shows like "The Wire," "Mad Men" and "Homeland" demonstrate that smart, serious narrative television is possible even if the audience remains relatively small, with most TV viewers chasing reality TV and overwrought singing contests. “It’s not often, in any society, that fewer consumers means more success,” says Brett Martin, a GQ correspondent with a new book, "Difficult Men," on TV’s new golden age.

But with television that’s exactly what it meant: For its first four seasons, "Mad Men" drew somewhere around 2 million viewers, chicken feed by the standards of the broadcast networks; big episodes of "The Sopranos" attracted more, but still not enough to land in the top 20 for their time slot. (Even its dearly anticipated season three premiere drew about a third the viewers of "Survivor: The Australian Outback.") The quality of this work, though, is undeniable. When the Emmys were announced this week, premium cable and Netflix dominated; the broadcast networks remained competitive essentially only in comedy.

So, where are the other quality niches, and just how many -- or how few -- fans does it take to make a great piece of work happen? And – even more important -- is the new wave of quality TV transferable to other forms of art and entertainment? Can a movie distributor, jazz club, theater company, book publisher or any other cultural institution produce its own "Deadwood" – and sustain it? Is the cable model -- small audiences, subscription fees, big buzz -- something that can be replicated?

*

By now, it’s old news that television has hit an unexpected sweet spot: Starting, arguably, with "The Sopranos," which made its debut in 1999, networks like HBO, Showtime, FX and AMC have turned out intelligent, open-ended shows with idiosyncratic characters, nuanced writing, and cinematic production values – series that have stayed on the air, generated deep passion from audiences, and been blessed by enormous media attention. (The lamented comedy "Freaks and Geeks," cancelled for low ratings after one season just as "The Sopranos" was getting started, seems to belong to a vanished, unjust world where smart shows disappeared before their time.) We’ve seen the violence and despair of the gold-rush era Wild West told in microcosm, watched the nation move both confidently and uneasily from the Eisenhower to the Nixon years through the lens of an ad agency, seen the personal, political and psychological entanglements of the war on terror, and squinted as a high school chemistry teacher in love with the periodic table turns into a drug dealer and cold-eyed killer. Shows like "Deadwood," "Mad Men," "Homeland" and "Breaking Bad" have become versions of the 21st century’s Great American Novel.

It’s easy to forget that -- despite the awards and all the media attention -- this is a handful of shows in a medium that continues to vary widely from the sublime to the ridiculous. But there’s no way to avoid noticing that television has gone, in barely more than a generation, from the tube some people boasted about not watching to the genre most likely to provoke dinner-party conversation. And while there were moments of quality in the past, much of it had a middlebrow-mainstream feel: The new TV is edgier. Los Angeles Times critic Robert Lloyd compared its best work to ‘60s rock ‘n’ roll transgressives the Velvet Underground. You couldn’t say that about "All in the Family," or "Cheers."

The wide spread of televised options has few parallels. “More than any other culture business, TV looks like America,” says Robert Levine, author of "Free Ride: How Digital Parasites Are Destroying the Culture Business, and How the Culture Business Can Fight Back." Movies skew toward teenage males, as does recorded music; novels toward adults, especially women. But there’s a station for everyone. “It’s the genuine mass medium,” he says.

Magazine journalist Martin digs into the complexities of TV’s evolution briskly and intelligently in "Difficult Men: Behind the Scenes of a Creative Revolution," which tracks especially closely on six series – "The Sopranos," "Deadwood," "The Wire," "The Shield," "Mad Men" and "Breaking Bad" -- which he compares to the auteurist cinema of the 1970s. And since this is auteurism, he gets deeply into the hearts and troubled souls of showrunners like David Chase, David Milch and Matt Weiner, whose almost dangerous intensity works its way into these series’ morally ambiguous anti-hero protagonists.

The talent was always there, according to Martin. “Driven, visionary people have always been around,” he says from his home in New Orleans, “and some will be hyper-sensitive to finding a hospitable host.” For a long time, that hospitable host was other spheres – the American novel, say, or the movies. But the planets lined up around the turn of the century, for television. A few enlightened executives slid into place. Technological developments meant a TV show could – with some work – look as good as a movie. The Internet created a community of rabid fans and recappers who generated cultural heat.

And the explosion in the number of channels changed the model. “It’s a competition to exist, to not disappear,” Martin says. “That created the world where the old metric of success – gross viewership – didn’t work anymore. Success did not have to equal ratings anymore. With HBO, Showtime, FX – especially at the earliest stage – that was not the most important thing. Creating ‘brand’ was, or creating buzz. An executive told me, ‘If AMC doesn’t come up with 'Breaking Bad,' you don’t have AMC.’ "

As enthusiastic as he is about the best shows, Martin wants to be clear: “It’s not that all TV got good – it’s that there was a place for good work to happen. And the reality of that particular business is that being a niche is enough. That’s my hope for the future.”

Near his book’s conclusion, Martin describes his “cause for hope”:

the new economic reality [means] that ‘success’ no longer requires a huge, or even very large, audience. As long as there is no true consensus audience for anything – or at least as long as the chase for one is relegated to the broadcast networks and the multiplexes – quality storytelling, fresh voices, challenging ideas, all the hallmarks of the Third Golden Age, may be able to remain another brand, a niche, right alongside home improvement, cute puppies, and weather disasters.

Sounds good. What’s not to like?

*

Of course, film has had auteurs and troubled fascinating characters for a very long time. (The auteur theory was being worked out in French film criticism as early as 1954.) Filmmakers with strong personal visions thrived in Europe and Japan in the ’50s and ’60s; in the U.S., the blossoming came in the ’70s, on the tomb of the studio system, with directors like Scorsese, Polanski, and Altman – Peter Biskind tells the story in "Easy Riders and Raging Bulls." As the narrative goes, the arrival of "Jaws" and "Star Wars" killed the maverick spirit and ushered in an age of blockbusters. But in the ’90s, independent filmmakers – mostly Gen Xers outside the Hollywood system like Richard Linklater and Quentin Tarantino -- revived the old auteurist swagger, and thrived alongside the corporate action films, which they often defined themselves against.

But when comparing the current state of American film and the flowering of quality television, Martin is a bit baffled. A lot of what made TV’s new heyday possible, he says, is specific to television. It’s not easy – and may not even be possible – to pick it up and drop its structures down into another field.

And the movies could really use the transfusion right about now. Forget about high-minded Altmanesque auteurism: Even making movies for grownups seems to be an eccentric idea. Another new book – Lynda Obst’s "Sleepless in Hollywood" – is less sunny than Martin’s. Obst, who produced "The Fisher King" and executive produced "Sleepless in Seattle," is not the first to lament the swallowing of intelligent, reasonably serious movies by sequels and turboed-out teenage fare: Film critic David Denby, for instance, wrote in his 2012 book that movies had become about “surface excitement and speed,” and were now places where the “characters get shoved off the set by special effects.” But it’s worthwhile to hear how it looks from inside the whale.

Movie studios, Obst concedes, have always been about show business, not about art. But for decades, they balanced blockbusters and sequels with romantic comedies, smart dramas, literary adapts and other adult fare about earthlings without superpowers. What she’s missing now, she says from her Culver City office, is what she calls “the middle movie, the one-off, the $30 to $60 million movies that the studios made as a matter of course, between the tentpoles which held up the slate.”

Those kinds of movies take a personal commitment from studio executives – “gut” -- and that’s become close to untenable. “Studios have to write P and L [profit and loss] statements,” she says, now that they’re all revenue-generating content providers for larger corporations. “They can’t write, ‘I love this movie,’ on it. That’s not the way it works. These days, when every call is a $250 million call, they don’t want to hear, ‘I believe in this movie’ They want to hear, ‘This will work in the international market, because…” They want a formula of special effects and Russian and Chinese action stars who can make the film huge. “You have to have a quantifiable algorithm. But you can tell from 'The Lone Ranger' – which seems to be losing its studio hundreds of millions – “that those things aren’t quantifiable.”

Looking more broadly at the film world, it’s hard to disagree. The most promising development of the last quarter century – the independent film movement, driven mostly by young directors making personal, idiosyncratic films – now seems like a specifically ’90s phenomenon. A few directors – Noah Baumbach ("Frances Ha") and Alexander Payne ("The Descendants") come to mind – have stayed the course. But they’re the exceptions -- and they don't feel especially relevant today. Despite a lengthy New Yorker profile and a starring role from It Girl Greta Gerwig, Baumbach's "Frances Ha" has grossed just $3.7 million since its release in May. It took Paul Thomas Anderson years to raise the money for "The Master," and it wasn’t the Scientologists who were dogging him but the values of the studios. Christopher Nolan, whose "Memento" is one of modern indie film’s most inventive efforts, now makes (smart) superhero movies. The careers of indie’s brightest lights match the movement of the film business itself: Some have gone straight, into the blockbuster business. Others have just disappeared.

More broadly: Optimists point to a handful of smart mid-sized movies from last year, such as the male-stripper story "Magic Mike," that not only got made, but performed well at the box office. That film’s director, Steven Soderbergh, was perhaps the most versatile of the indie directors, in both scale and subject matter. He’s since announced that he will stop making films, and his last project, on Liberace, showed up on… HBO -- despite starring Michael Douglas and Matt Damon.

Even Steven Spielberg – who ushered in original blockbuster era – struggled to get "Lincoln" made. He said recently, at a speech at USC, that Hollywood was so thick with would-be blockbusters now that it was on the verge of collapse. This is the director with perhaps the highest combination of box office muscle and critical respect of any filmmaker alive, and his biopic with one of the world’s greatest actors, about America’s most visionary president, almost ended up a TV movie.

How did we get here? A lot of this comes from studio bloat. “From May 1 to July 4, studios will have released 13 movies costing $100 million and up (sometimes way up), 44 percent more than in the same period last year,” New York Times reporter Brooks Barnes wrote in a recent story on the blockbuster madness in Hollywood. “Because these pictures need to attract the biggest global audience possible, they are increasingly manufactured by committees who tug this way and pull that way: marketing needs this, international distribution needs that.”

To Obst, the key was the collapse of DVD sales around 2005. Those little discs never sold the way CDs did – they were just one of film’s revenue streams – but for a decade or so, the studios earned about half of their revenues from them. With the loss of DVD sales, she says, studio profit margins went from about 10 percent to around 6 percent, and the Great Contraction arrived. This made Hollywood vulnerable to the next thing that came along. And the next thing that came along was too big to resist: the emerging international market.

“We always exported our films,” says Obst, “and our movie stars were always the world’s stars.” Many countries – France, India and so on – had their own thriving film industries. The balance changed, though, around the time the domestic DVD market was losing steam: High-impact digital technology, such as 3D, made mega-films like "Avatar" and the Harry Potter sequels possible right as Russia and China were opening up to both capitalism and movies. These new markets went crazy for these films, and provided the studios with the financial jolt they needed. “They thought, ‘We will be able to thrive, or at least to live.’ But those movies were astonishingly expensive.”

And there was a kind of film that didn’t travel. Or really, almost any kind of movie with an original storyline – not taken from a comic book, video game, theme-park ride – aimed at a grownup audience, and with more conversation or psychology than explosions. “They don’t want writing or nuance,” Obst says. “They don’t want our jokes; they want jokes that are specific to their own cultures.” What they want is “pre-awareness” – a movie about something they already know about. Like a superhero. Or a movie they saw last year, like one of the "Fast and the Furious" franchise.

These days, the Chinese market is either a physician jolting adrenaline into an ailing Hollywood, or a bully driving all the serious, grownup films away. In 2012, Chinese audiences spent $2.7 million for movie tickets, a jump of 36 percent from the year before, and nearly 10 new cinema screens per day are going up, most 3D or IMAX theaters, designed for blowout action movies. “China will be the number one market in 2020,” Obst says. “It’s phenomenally important.”

This summer, as would-be blockbusters like "After Earth," "White House Down," "The Lone Ranger," "R.I.P.D." and "Pacific Rim" lose tens of millions of dollars, salvation is coming not from intelligent indie films of the kind Hal Hartley or Spike Jonze used to make, nor the mid-priced one-offs Obst pines for, but horror movies, sequels for kids, and Adam Sandler films: The reasonably inexpensive "The Conjuring," "Despicable Me 2" and the toilet-humor driven "Grown Ups 2" (probably not the grownups Denby was asking for) are likely to be among 2013's big winners.

And where once we had an indie film movement based on mid-sized films, many made by a cinematic middle-class and with stars like Harvey Keitel or Nicole Kidman taking pay cuts, today we’ve got no-budget films unleashed by digital cameras. Obst calls them “babies with iPhones,” turning out “this enormous proliferation of tadpoles, made basically for free.” Some, of course, are quite smart. “The only thing wrong with them is that the crew doesn’t get paid. But they are our solution.”

*

The music business experienced its own Great Contraction – with Internet piracy and then iTunes – a few years before it hit the movie studios, and much of it simply evaporated. But independent labels, for the most part, have held on. The “quality” niche in rock music is not lavish, like it is in television – none of these records sound the way "Mad Men" looks. And these labels don’t have sleek offices like HBO’s in Santa Monica. But the successful indies are better than the movie’s blockbuster-and-tadpoles model. The middle may be disappearing, but at least a handful of musicians and their handlers can earn a living. And the best of these labels are laboring to find art – or at least tuneful, guitar-driven indie rock -- in a race-to-the-bottom world. They’re doing it in a time when record sales have shriveled, but still produce some income.

“There are small labels that can print up 500 LPs and break even,” says Nick Blandford, who serves as managing director of the Bloomington, Indiana-based Secretly Label Group. The labels he oversees -- Dead Oceans, Jagjaguwar and Secretly Canadian – scale a bit larger than that. But the model for the Secretly labels – and a number of other indies – is pretty bare bones, and shows how drastically sales figures have dropped since the ’80s or ’90s.

“We normally need to sell 4,000 or 5,000 records worldwide,” he says. “That’s our floor. And it can go up considerably from there, if you want to make a bigger bet.” In the case of the labels’ best seller, the rustic crooner Bon Iver, his two full-lengths on the Jagjaguwar label have sold more than half a million copies in the U.S. alone. But unlike movie studios, indie labels don’t make every bet a $250 million one: They can put out something yearning and profound like Damien Jurado or Magnolia Electric Co. And unlike the model the major labels typically used, the Secretly labels don’t expect a few blockbusters to pay for everyone else. “I don’t think it’s fundamentally transformed how we’ve done business,” Blandford says. A hit “pushes you forward; you learn new things. But we’ve always put out small records; we know how to do that in a sustainable way.” A big seller allows them to put a little more muscle behind some recent debut records by Foxygen, Nightbeds and Cayucas.

But: “Our goal is for every record we release to break even and become profitable – if they’re selling 5,000 records, or 15,000, or whatever.” Somewhere around the 15,000-sales mark, he says, a band that tours aggressively and develops a following can quit its day job and devote itself to music. It helps that these days, indie labels often split profits on record sales 50/50, after an album earns out its small advance.

“The key to the record business,” says Robert Levine, “is, ‘Don’t spend a lot of money on stupid shit.’ If the CD costs you $3 to make, and you sell it wholesale for $10, and you sell 20,000 copies… That’s a lot of money if your offices are in North Carolina and you don’t fly first class.” The two models of culture in the Internet age, he says, are, “How cheap can we do this?” and, “How great can we make this?” Indie rock is in the curious position of trying to do both at once.

The Secretly labels don’t have lavish Manhattan offices – besides their homebase in Bloomington, their New York presence is in Brooklyn’s Greenpoint neighborhood – and they don’t typically help bands with touring. Recording advances, somewhere between $5,000 and $50,000, Blandford says, don’t allow a band to spend months in the studio with a fancy producer. (Sometimes it buys them a few months to write songs.) The labels do some marketing and publicity, but they are not typically buying full-page ads in Rolling Stone. The three Secretly labels employ 24 people full-time, putting out about 25 albums per year.

Compared to the old days, then, labels don’t do as much. Other indies show that strong, original work can be produced in a system with small stakes. The most consistent batch of quality releases may come from Merge Records, whose offices really are in North Carolina. Chapel Hill-based Merge puts out about 32 new albums a year, with a full-time staff of 14, with several new signings on every roster. (The label, founded by two members of the band Superchunk, releases records by a few bestselling bands -- Arcade Fire and Spoon – as well as releases that appeal to small but fierce audiences, such as Teenage Fanclub, M. Ward, the Radar Bros. and the Clientele.)

“Well, we’re not getting smaller in spite of the rest of the music business shrinking,” Merge-co-founder Laura Ballance told Salon’s David Menconi in 2011. “We try not to overspend and always hope we’ll break even. There are bands we still release that we just know are not gonna sell much. But that’s not why we put them out. We put them out because we like them and believe in them.”

Matador and Sub Pop (which almost collapsed after some big sales tempted it to act like a major) now work roughly the same way, putting out strong work by the Shins and Beach House (Sub Pop) and Yo La Tengo, the New Pornographers and Belle & Sebastian (Matador).

And unlike Hollywood, where personal taste has become beside the point, it’s a crucial ingredient to the way indie labels work. “It’s essential; that’s where we start,” Secretly’s Blandford says. “The first thing we look at is, ‘Do we love the record, do we love the band? Does it fit the aesthetic of the label?’ When those questions are confidently answered we ask, ‘Can we do it in a sustainable way?’ ”

*

What indie labels don’t do is have the budgets to produce anything as lushly stylish or culturally defining as "Mad Men," or as politically and sociologically heavy as "The Wire." The indies are keeping the tradition of Sonic Youth and early R.E.M. alive, but it’s hard to argue we’re in a golden age of rock music the way we undeniably are in television. (Is it any wonder than writers and directors are leaving the movies for television -- despite the fact that these "quality" shows, while making millions for their networks and being extraordinarily demanding to helm, earn directors dramatically less money based on the Directors Guild of America scale?)

So is there a way to make these other culture businesses work the way cable TV does – and produce some high-quality, substantial, critically acclaimed work that’s actually popular? Well, probably not.

A number of elements make television different. In the simplest sense, a new episode of a show with a fierce following – like the cable shows Brett Martin chronicles – becomes obligatory water-cooler conversation in a way that even a hit movie or popular record doesn’t. Despite the efforts of Netflix – whose "House of Cards," "Arrested Development" and other series can be streamed at a viewer’s whim -- TV typically depends on a sense of who-shot-J.R. “event” around a new episode. If you want to avoid knowing what happened on "Game of Thrones" or "Homeland" or "Girls," you pretty much have to stay off the entire Internet. And while piracy of TV shows (or sharing an HBO Go pass) is not unheard of, it hasn’t devastated the medium the way it has other fields. The Internet – dangerous, mostly, to most other types of culture – may have helped these cable shows by generating a dedicated community around them.

But the biggest factor that makes the "Sopranos" revolution work is what’s called bundling, where a cable company – Time Warner, say, or Verizon – puts a bunch of different channels together and charges you accordingly. Each channel charges the cable provider a carriage fee. (ESPN, by the way, charges a lot, and you're paying regardless of whether you watch "SportsCenter.") This puts the power in the hands of the people making the shows.

“It’s incalculable how valuable 'Mad Men' was,” says Martin. “When a network’s finances come from carriage costs, shows like that are priceless. If Cablevision drops AMC, your 'Mad Men'-loving population cries bloody murder, or goes to satellite, or DirecTV. That’s what identity does for you.”

All culture merchants work to develop identity – or “brand” – but only in cable does it work quite this way. “Cable is unique because you have a bundled system,” says Levine. “If you’re buying only the top shows, there’s no room for error. The fact that cable’s bundled allows the risk of greatness. Is it fair to make people pay for 100 channels if they only want three? It’s a bad thing for consumers, but it’s probably good for television. Is it legally problematic? So far the courts have said no, despite many legal challenges.”

Bundling and carriage costs also lead to variable pricing that doesn’t exist in other fields. “If you do something great,” Levine says, “people will pay more for it. While a movie costs about $10 to see whether it’s good or bad, and every CD costs about $12.”

Subscription fees in music, for example, seem to end up putting very little money back in the hands of the artist. Satellite radio pays a very low royalty rate. Spotify and Pandora turn fans on to new artists but also have proven controversial. Last week, Radiohead's Thom Yorke removed his solo recordings from Spotify because, as he tweeted, "new artists get paid fuck all with this model."

Added Radiohead producer and Yorke's Atoms for Peace partner Nigel Godrich: "The numbers don't even add up for Spotify yet. But it's not about that. It's about establishing the model which will be extremely valuable. Meanwhile small labels and new artists can't even keep their lights on. It's just not right."

Could you bundle other sorts of culture, so that the stuff that sold helped pay for the risky or less-lucrative but still valuable stuff? In most aspects of culture, that’s the old model. In the old days, Martin says, “Newspapers could sell ads on their features sections, making them money that paid for other things.” Like foreign bureaus, say, or book reviews. “It was part of these mandarin old media concerns – a network, a record label, a book publishing company that would put out a book of poetry. That is over.” Except on TV -- the one cultural form where people seem willing to actually pay, and pay a lot, for content.

It’s still, often, the subscription model for the art forms that evolved before the market economy – the way the ballet company sells a subscription that includes "The Nutcracker," which will sell out for two weeks, and three or four things that won’t, or the local orchestra puts on a few celebrity-driven events or “family friendly” pops concerts that earn it revenues to put on symphonies that are expensive to put on and chamber music that draws a small audience.

Each cable network doesn’t offer that kind of range – this channel’s all home refurb, that one’s all tornadoes – but bundled together, they do. So cable’s success may be, in a sense, not the wave of the future but a kind of throwback.

Levine can imagine a few bundling possibilities in other fields – “Could you bundle a few newspapers with a magazine? Or if the New York Times doubled its subscription price, and every week came with a new book? Could they bundle in 'Frontline' documentaries?” He’s not so sure. It’s hard to imagine this being a model for the future, as the general culture moves deeper into all-against-all blockbuster territory and the Internet undercuts the money made from cultural content.

In fact, the cable-quality model may not even transfer to other outlets within the world of television. A show as strong as "Friday Night Lights," Martin points out – with a readymade audience from a hit movie and book -- limped along during its run on NBC and DirecTV.

Levine’s book chronicles some of the Internet’s threats to TV’s new heyday – legal and otherwise – but he’s more hopeful than he is about music or movies. “I’m optimistic about TV, because you seem to have a race to the top rather than a race to the bottom. TV is the only medium where tech companies are investing in content. They’re trying to do the same thing cable does. ‘Can we do something so good – can "House of Cards" generate enough buzz – that people have to get Netflix?’ You don’t see it happening in film. Tech companies are not giving money to artists.”

Another comparison between TV and film is useful, says Martin. “Where once all of Hollywood made a shift to commercial entertainment after 'Jaws' and 'Star Wars,'” Martin says, “there is no ‘all of Hollywood’ any more. There is no ‘all of’ anything’ anymore.”

For now, he’s placing his bets that niches and fragmentation will continue to produce good work, even if the Difficult Men generation may be ceding to TV auteurs more like Lena Dunham, and a different kind of show. But he thinks that while the tone of television’s best shows will change, quality will continue to exist, at least on cable. “We shouldn’t cease,” he says, “to be grateful.”

The rest of us, though, will have to wait and see.

Shares