When I heard that the Irish poet and 1995 Nobel laureate Seamus Heaney had died, I reached for a slim volume of his called “Field Work” that I keep on the shelf near my desk. It begins with a violent and possibly erotic poem called "Oysters":

Alive and violated

They lay on their beds of ice:

Bivalves: The split bulb

And philandering sigh of ocean.

Millions of them ripped and shucked and scattered.

I'm not so sure that's really about oysters. The title of the book is also ambiguous, reflecting Heaney’s concern with the natural world and the rhythms of agrarian life, and containing various meanings as an Irish bog might contain ancient artifacts or perfectly preserved medieval corpses. Field work is done by farm hands, and also by scientists, archaeologists, engineers. By writers too, Heaney would say. He saw poetry as an ancient craft and practice akin to agriculture, much older than what we would now call civilization. It follows the rhythms of life and death, winter and summer, asking the same questions of the earth and of us over and over again, and yet the results are never quite the same.

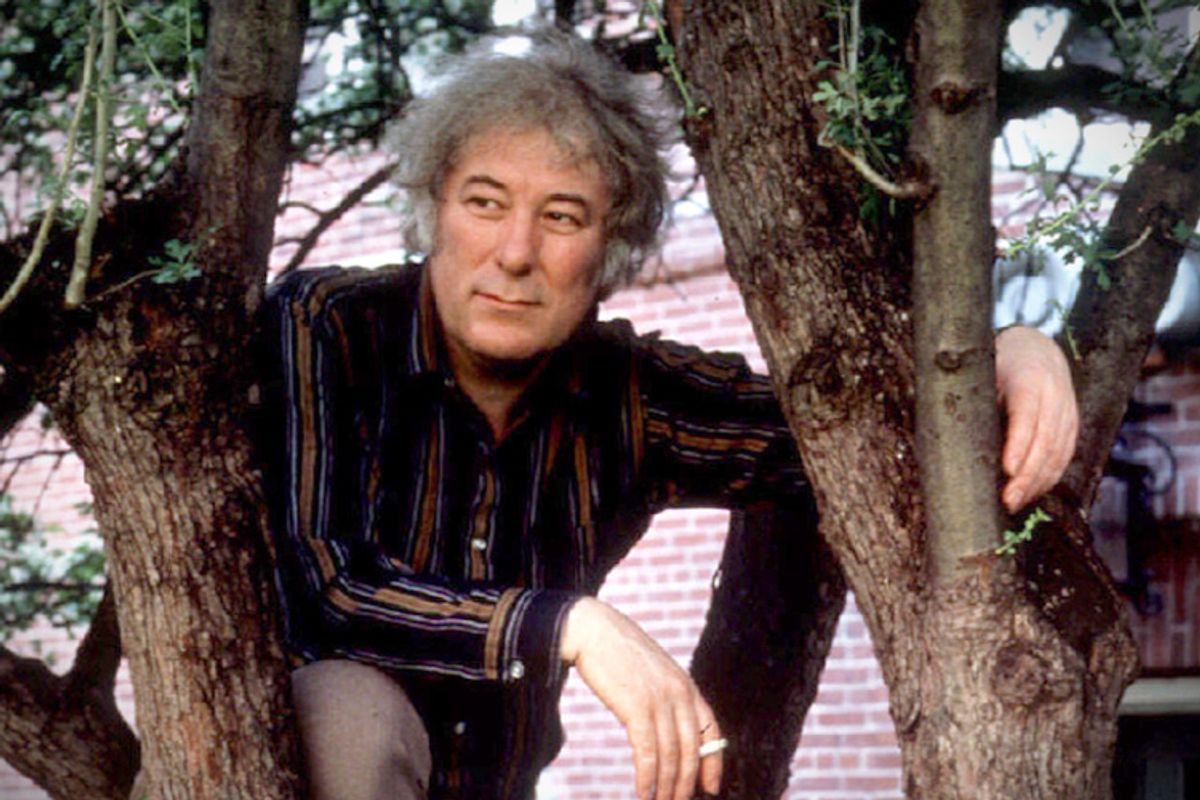

“Field Work” was published in 1979, and as I hefted the book in my hands I reflected that I must have taken it off my father’s bookcase after he died. As a child in the early 1970s, I had the vague impression that Heaney was a member of our family, just another of my dad’s garrulous Irish cousins who came and planted themselves in our Berkeley living room, smoking and drinking whiskey and contending about politics and literature and sports deep into the night. He was charming and sardonic and could quote long literary passages from memory, and always remembered to include a serious, owl-eyed little boy in the conversation. But the same could be said of my father’s Uncle Perry, who sat up late with me one night to watch George Foreman knock out Joe Frazier.

After a spell as my father’s colleague at the University of California and a few extended sessions in my parents' house, Heaney went back to Ireland and then onward to Harvard, Oxford and elsewhere. It took me some years to understand that the shaggy 30ish fellow I remembered from our sofa had become the most important Irish poet since William Butler Yeats, and almost the only serious literary poet of our time to attract a wide popular following. It took even longer to grasp that nothing about my personal experience with Heaney was unique, or even unusual. He touched thousands of people the same way; nearly everyone he ever met can spin anecdotes about him.

One could say Heaney had the common touch, but that makes it sound calculated or strategic, like a politician’s or movie star’s marketing plan. Unlike so many great writers with their tendency toward introspection and isolation, Heaney was naturally gregarious and loved meeting people. While his poetry was full of references to Celtic mythology and classical literature, he always meant for it to be read aloud and to sound like spoken English (of our own time, or the past, or another yet to come). As Brad Leithauser put it in a New York Times review of Heaney’s 2006 collection “District and Circle,” he had “the gift of saying something extraordinary while, line by line, conveying a sense that this is something an ordinary person might actually say.” Although this aspect of Heaney’s biography is often overlooked, he began his career teaching in a secondary school and a teacher’s college in Belfast. He always saw himself as a craftsman, a worker in the fields of literature, who sought to make connections with an audience far beyond the inbred circle of poets and academics.

Heaney came to Berkeley in the ‘70s as a star representative of the burgeoning Irish-nationalist literary scene in British-ruled Northern Ireland, which was then near the beginning of a quarter-century of intimate, low-intensity civil war. He never disavowed his symbolic role as a spokesman for the province’s embattled nationalist community, and always identified as Irish rather than British, demanding a retraction from the Observer when it named him among “Britain’s top 300 intellectuals” in 2011. But Heaney also never defended or romanticized violence, and his work and his life ultimately had very little to do with sectarian politics or nationalist ideology. In “Digging” (1966), probably his best-known poem, Heaney first compares the pen in his hand to a gun, a deliberately disturbing invocation of the Irish tradition of murder and martyrdom. Then, after observing or remembering his father digging potatoes and his grandfather cutting turf, the metaphor shifts and the gun is set aside. He has the same “cold smell of potato mould, the squelch and slap/ Of soggy peat” in his head that his forebears did, the poet writes.

But I’ve no spade to follow men like them.

Between my finger and my thumb

The squat pen rests.

I’ll dig with it.

Indeed, within the context of recent Irish history, Heaney’s life and career have been exemplary. As Ireland’s most important literary export of the last 50 years, and its first Nobel laureate since Samuel Beckett, he played an important role in the nation’s ambiguous journey out of the past and in, let’s say, its changed relationship to ancient conflicts and unforgotten grievances. If the way Ireland has been transformed by capitalism in recent decades is a mixed phenomenon at best, a saga of craptastic technology parks and faux-authentic tourist attractions and speculative booms and busts, Heaney represents something far more positive. He embodied the idea that Irish literary culture could remain vibrant and distinctive while moving past its drink-sodden, God-haunted stereotypes, its isolation and xenophobia. He remained philosophically and poetically rooted to his upbringing in a rural townland of County Derry (of course he never would have called it Londonderry), while also becoming a major figure in world literature, drawing on the traditions of ancient Greece, Eastern Europe, Africa and beyond.

Despite his personal investment in not being identified as British – Heaney declined the post of United Kingdom poet laureate, while politely adding that he’d met the Queen and had nothing against her personally – he also understood that in the long run there’s no way to disentangle the history or literary traditions of those two islands. There are certainly echoes of Yeats in Heaney’s verse, along with exchanges with other modern Irish writers like Patrick Kavanagh, John Montague and his onetime Derry schoolmate Seamus Deane (who also did time on our living room sofa). But his poetry is just as closely allied to a British tradition that includes William Wordsworth, Gerard Manley Hopkins and his friend Ted Hughes, with whom he edited two marvelous anthologies of poetry for young people. It has often been noted that Heaney's poems about the Irish “troubles,” as in the volumes “North,” “Wintering Out” and “Station Island,” avoid overt political statements or Irish republican cliché. But in fact he was never interested in an essentialist vision of Irish identity at all, which frustrated some dogmatic nationalists eager for agitprop. He wrote about violence in Ireland because it happened and he was there; he thought of poetry as a form of especially acute observation and record-keeping, rather than commentary. Poets, he wrote, “are finders and keepers … their vocation is to look after art and life by being discoverers and custodians of the unlooked for.”

For much of his career, Heaney both literally and figuratively left the Northern Ireland conflict and the tormented history of Anglo-Irish relations behind. He spent more than 20 years teaching at Harvard, where he translated and adapted ancient Greek drama and 20th-century Eastern European poetry. (He was an early champion of Polish poet Czeslaw Milosz, the 1980 Nobel laureate.) In that light, Heaney’s vivid and gripping 2000 verse translation of the Anglo-Saxon epic “Beowulf” (which stands a good chance of being his most enduring work) feels like a kind of summing-up, both a warm embrace and a subversive celebration. In breathing new life into a dusty classic often dreaded by English majors -- and every so often slipping in a distinctively Irish dialect word or turn of phrase – Heaney did what Irish writers have done for generations, inheriting the language of their one-time overlords and loving it, burnishing it, turning it to their own purposes.

Heaney would be more amused than dismayed, I hope, to learn that his anthology “Opened Ground: Selected Poems, 1966-1996” – probably the best one-volume introduction to his work – has soared to No. 1 on Amazon’s “British Poetry” page. (At this writing, other Heaney books fill seven of the next eight slots on the list, the other writer represented being Shakespeare.) In life and on the page, he transcended the “Irish question,” but death makes a fool of us all. That brash young man I remember smoking cigarettes on my parents’ sofa understood that all along.

I met Heaney just once more, many years later; he was kind and claimed to remember me, which seemed unlikely. When my father died, he sent his regards through a mutual colleague and asked after my mother (who is also a poet). That was also kind, but I got much more satisfaction from a poem about death he wrote soon after that. It certainly seems the right one to return to now, with Heaney himself gone much too soon. It was actually written as an elegy for the Nigerian academic Donatus Nwoga, who introduced Heaney to Igbo traditional verse. In the poem, a dog is sent to the deity Chukwu to deliver the message that human beings want death to be temporary, “like a night spent in the wood.” But the dog gets distracted along the way, barking at another dog across the river, and someone else takes up the mission:

And that is how the toad reached Chukwu first,

The toad who’d overheard in the beginning

What the dog was meant to tell. “Human beings,” he said

(And here the toad was trusted absolutely)

“Human beings want death to last forever.”

Shares