How does one explain the fact that a leading figure in analytic philosophy and linguistic theory – abstruse academic fields that are not readily comprehensible to the layperson and have almost no practical or everyday resonance – has become America’s most prominent public intellectual and its leading anarcho-libertarian voice of dissent? Needless to say, most people who have read Noam Chomsky’s numerous works of political polemics about American imperialism, the mass media and the Middle East have not read “Language and the Study of Mind,” let alone “Morphophonemics of Modern Hebrew.” But there is a relationship between the two Chomskys, and also a person behind them, whom almost nobody knows. That impossible combination is what French filmmaker Michel Gondry sets out to capture, after his own peculiar fashion, in “Is the Man Who Is Tall Happy?: An Animated Conversation With Noam Chomsky.”

Yes, it’s a cartoon. About Noam Chomsky. This defiantly strange little film cannot account for Chomsky’s celebrity, or the vibe of semi-macho coolness now attached to his public reputation. Mike Tyson supposedly read Chomsky (along with Mao Zedong) while in prison; NFL star turned Army Ranger Pat Tillman supposedly read Chomsky before his death in Afghanistan. He came up again in the sports pages last week, when Denver Broncos lineman John Moffitt cited Chomsky as an influence in his abrupt decision to quit football and walk away from a million-dollar salary. I will tell you frankly that “Is the Man Who Is Tall Happy?” is not just for Chomsky acolytes, or for fans of Gondry’s handmade movies and videos (from the Chemical Brothers to “Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind” and beyond, although we're all going to pretend that "The Green Hornet" never happened). You really need to be both at once. There’s no doubting the authentic passion at work in this often-bewildering experience, but the Venn-diagram population of those who will find delight in it may be pretty small.

Gondry conducted two extensive interviews with Chomsky in the latter’s MIT office in 2010, recording the whole thing on digital audio and filming a few snippets with an old-school Super-8 camera (which adds that comforting low-tech whirring noise to the background). So we sometimes see Chomsky during the course of this movie, but almost always in a little box in one quadrant of the frame, surrounded by Gondry’s hand-drawn, faux-primitive animation, which ranges from pure abstraction to childlike illustration to Keith Haring-like symbolism. Their conversation is mostly about Chomsky’s life, especially his childhood, his education and his family, or about his academic career and his controversial hypothesis that a universal “generative grammar” lies beneath all human language and communication. Beyond a few glancing references to educational philosophy, the Middle East and Chomsky’s visits to Latin America, there is no talk of politics, and United States foreign policy – the issue that has made Chomsky a left-wing icon – is never directly mentioned.

If you’ve followed Gondry’s career – and especially if you’ve ever encountered him in person – it won’t surprise you that he’s especially captivated by the moments of communication or miscommunication that inevitably come up between a fast-talking American philosopher and a heavily accented Frenchman with a shaky English vocabulary. There’s an entire episode about Gondry’s struggle to pronounce the word “endowment,” and to understand what Chomsky means by it (in the context of an evolutionary or genetic inheritance). Even the pointedly confusing title of the film is simultaneously a Chomskyan attempt to explain his ideas in ordinary language and the creative result of a malentendu, as Gondry might say back home. Gondry suggests a similar sentence, but not that one, as an illustration of Chomsky’s generative-grammar hypothesis, and Chomsky repeats it incorrectly: “Let’s take that sentence: ‘Is the man who is tall happy?’ Or whatever you just said.”

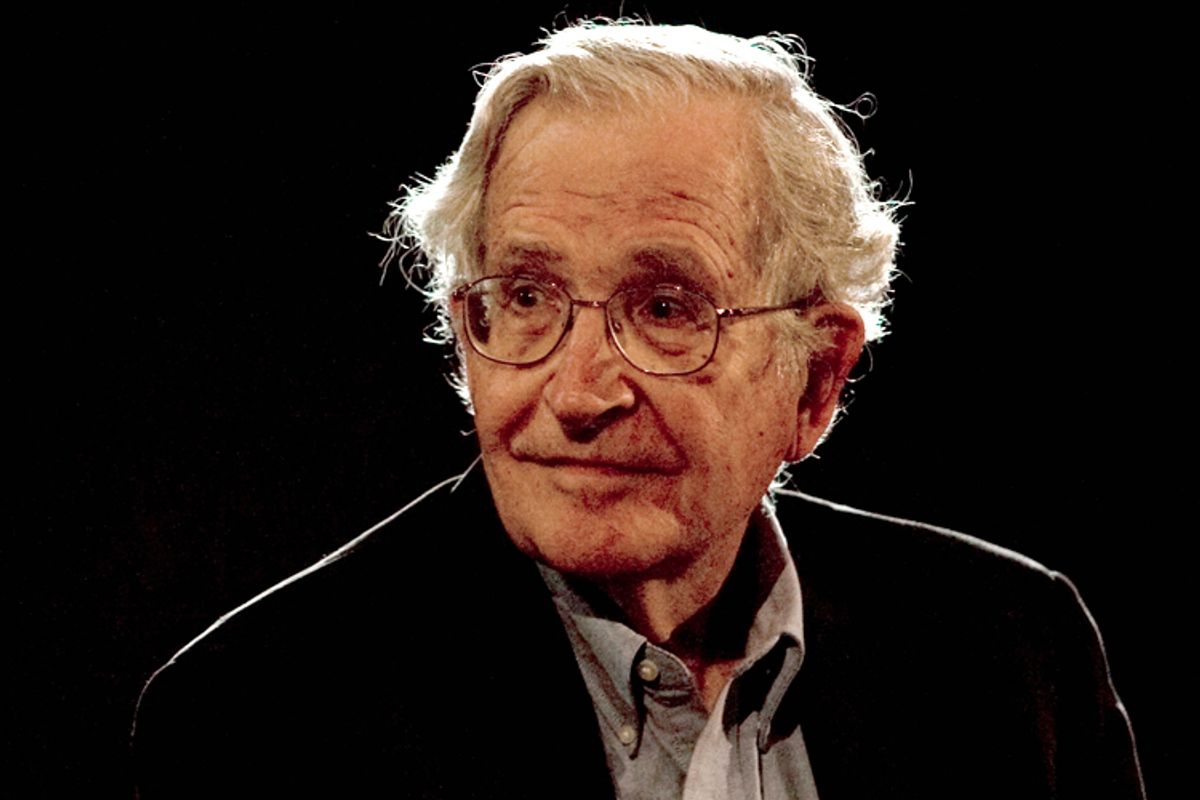

It’s impossible – for me, at least – to avoid noticing that Chomsky himself is neither tall nor happy. He’s a mild-mannered, wizened and elderly man (now 85) who is notably ill at ease discussing his own life, especially in the present tense. (His memories of his Philadelphia childhood, and his erudite Hebrew-scholar father, on the other hand, are fond and evocative.) Although he’s obviously aware of his celebrity status, Chomsky takes no interest in popular culture or the arts, never watches television or goes to the movies, and reads only nonfiction. He views rock music, he says at one point, with the same polite puzzlement as he views religion. Both are clearly important to many people and form the basis for meaningful community. He doesn’t begrudge anyone their pleasures, but he simply doesn’t get it. (Chomsky has objected on epistemological grounds to being labeled an atheist: Until you can explain exactly what it is he’s not supposed to believe in, he says, the term doesn’t fit.)

Perhaps you can’t quite be a “normal person” and do all the things he has done, but Chomsky has remained an unassuming figure throughout his career, until very recently answering his own office phone and granting interviews to anyone who asked. When Gondry eventually asks what makes him happy, Chomsky has difficulty answering. He doesn’t think about that, he says. Family makes him happy, children and grandchildren – but this is said reluctantly and with irritation, as if he knows it’s what you’re supposed to say. Finally he remembers visiting Colombia, where a group of indigenous people planted trees in memory of Chomsky’s late wife. As I understood his response, it wasn’t the personal gesture that affected him but its social meaning and social context, that being an anti-authoritarian group organized to resist the neoliberal and imperial world order.

If you want to understand how the convoluted question of the title supposedly elucidates Chomsky’s theoretical universal grammar, see the movie. I’m not the right person to defend the whole thing. (My father, I should say here, was a philologist and language scholar – although not technically a linguist – who strongly opposed the Chomskyan idea that language stems from some innate and inherited communicative capacity that is uniquely human.) But Gondry’s odd achievement in “Is the Man Who Is Tall Happy?” has nothing to do with whether you agree with anything Chomsky has ever said, about language or the United States or anything else. This film captures Chomsky as a human being – a sweet and sad and rather lonely one, truth be told – without ever belittling his questing intelligence, his generosity or his ferocious assault on the entrenched narratives of power.

“Is the Man Who Is Tall Happy: An Animated Conversation With Noam Chomsky” is now playing in New York and Los Angeles, with more cities to follow. It will also be available on VOD, beginning Nov. 25, from cable, satellite and digital providers.

Shares