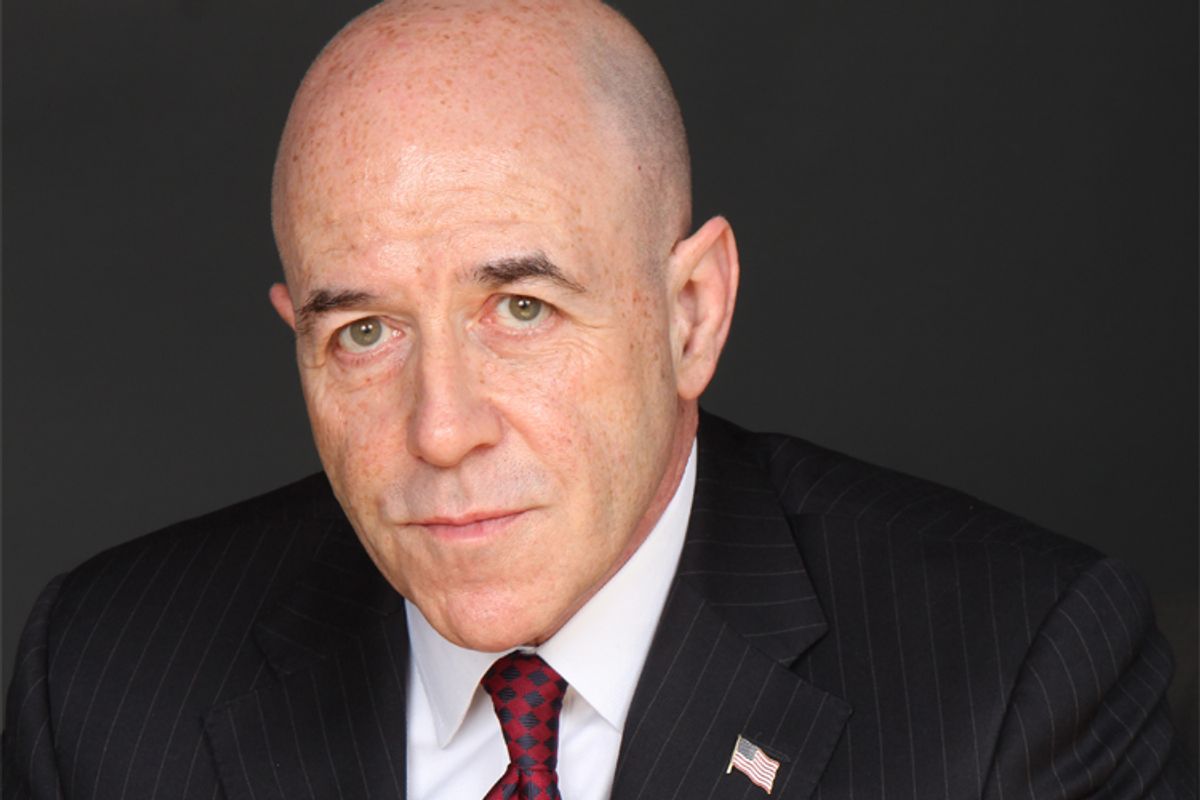

In 2010, former New York Police Department Commissioner Bernard Kerik was sentenced to a four-year prison term for felonies including tax fraud and lying to White House officials. Kerik, whom President George W. Bush installed as interim interior minister of Iraq and (unsuccessfully) nominated to run the Department of Homeland Security, pleaded guilty on eight felony charges. Last month, in his first speech since his release, Kerik announced that three years in jail had converted him to the cause of criminal justice reform.

“Nobody in the U.S. criminal justice system is made whole once they're convicted of a felony,” Kerik told Salon, urging reforms to sentencing and the eventual erasure of felony convictions from ex-offenders’ records.

But asked if his time in prison had left him with any regrets about his stint helming the NYPD, Kerik answered, “No. No.” Kerik, who ran the NYPD in late 2000 and 2001, said he lacked the data to conclude whether stop-and-frisks under his successor Ray Kelly had violated constitutional rights, but said if the city were to abolish plainclothes police officers’ ability to stop-and-frisk, “you should just put them back in uniform … and let the guns and drugs and bad guys go rampant…” A condensed version of our conversation follows.

What was your view of mandatory minimums before your time in jail?

I don't know what my view was. I didn't pay much -- I knew there were mandatory minimums in the private federal system, I knew there were mandatory minimums in the state system. But for the most part, you know, it was the prosecutor’s job. You know, as a cop, as a law enforcement officer, as an executive, you don't -- you're not -- I guess you're not -- I don't know how to say it. You're just not -- you don't look at them. You let the prosecutors do their job, so to speak.

How did your view of mandatory minimums start to change?

I have been in law enforcement my entire career … I have put people in prison for many years … But these people were bad people that did bad things. They were people who tried to kill me. People that killed my partners, people that I seized millions of dollars of drug proceeds from … I have no problem with those people going to prison for those lengths of time.

Where I have a problem is when I went into the federal system, and I realized that there were young men sentenced to 10 years, 15, and 20 years -- for first time, nonviolent drug offenses. For really low-level possession drug offenses, that basically got tacked onto some conspiracy … quite often a third-party, fourth-party conspiracy, the target of which they did not even know. They could have had a gram of cocaine, five grams of cocaine, and they wind up going to prison for 10 years or 15. That is wrong. The punishment doesn't fit the crime.

Did your attention to it come from direct conversations that you were having with people who you were --

Yes. Basically it was a minimum security camp where I was being held … I'd say out of the 300 men, 75 to 80 percent of them were there on drug charges. And many of them were young men … Many of them were there on first-time offenses … all nonviolent offenders …

I taught a class, a life lessons class, to the men at this camp for the DOP, and during the course of teaching that class, you know, we would discuss their charges … Quite often ... they would take a plea that overcharged the reality of their crime … I learned a lot about the mandatory minimum sentencing guidelines.

When you consider the amount of time that you spent in jail for your crimes, and the amount of time they spent in jail for their crimes, is there an injustice in that contrast?

I think we have to look -- in the United States today -- we have to look at the reality that prison is not necessary as a punishment in many circumstances …

Somebody is sentenced to prison and there's an article that says, “Well, it looks like a slap on the hand,” and people are outraged because they didn't get a longer sentence …

In reality, there are many, many people, both men and women, who go to prison [although] they didn't need prison to – one -- to learn their lesson; they didn't need prison to pay their debt to society; and they didn't need prison to be punished. Because their punishment is enormously severe before you ever get there ...

Even if you didn't spend a day in prison, if I personally, me -- I was sentenced to 48 months, and I did three years and 11 days inside. Then I had to do another five months in my home. But if I was sentenced to probation, only to probation, I am still going to be a convicted felon for eternity. For the rest of my natural life, until the day I die. And the collateral consequence of that label of convicted felon is far more damaging or devastating than anybody in the American public knows unless you've been through it.

So I'm not -- I don't have to talk about me. I can talk about any convicted felon that either goes into the institution … or gets sentenced to an alternative. The punishment is severe already. It's enormously severe.

Look at it this way: A convicted felon has a 70 to 75, maybe 80 percent chance less to get a successful job than one of his peers that's not convicted … I know [men] with master's degrees and Ph.D.s that cannot get a job. They can't get a job at McDonald's because they are a convicted felon. So if those men can't get a job, how do these young black men out of D.C., or Baltimore, or New York City, or anywhere in urban America, that got convicted on a low-level drug crime that turned out to be a felony -- how does that kid get a job? It's never going to happen …

What it has evolved into today, punishment doesn't fit the crime. You are sentenced to life once you are sentenced to a felony – once you are convicted of a felony, it is a lifelong sentence and it's wrong -- it shouldn't be. If we're going to [say] … we should abide by the laws and punish for violations of the law -- well, then we should also abide by the fact that once you're punished, once you've served your debt to society, then you're made whole. But nobody in the U.S. criminal justice system is made whole once they're convicted of a felony.

And unfortunately, it's something that I never thought about. I never -- I just didn't think about it. Nobody does. Nobody does. Until they are actually in the system, or until they've had some sort of personal discourse with the system -- a family member, a friend -- they've had some personal contact where they’ve been able to see it on their own …

I gave a speech, and a woman asked me … why is it that people like you … the only time they come forward and advocate for change is once they've been in the system? And the reality is the only time anybody advocates for change in our criminal justice system is once they become aware of it … You're not going to fight for something that you have no concern for … You're not going to fight to fix something if you don't know it's broken … I can promise you that the congressmen, the legislators, they don't know what the actual collateral damage the system does … If I didn't know, I'm damn sure positive that they don't know …

Are you saying that while you were police commissioner, you weren't thinking about what would happen to people after they went to jail?

It's not that you don't think about people … I've been a cop, I've been a detective, I've been a correction officer. I ran Rikers [Island prison complex] for six years, and I was the police commissioner. You are focused on enforcing the law. And that's what you do.

You enforce the law, the laws that exist, the laws that are written. It's not your position to question those laws or to, you know, analyze, you know, the impact of those laws … But the judges and the attorneys, and the prosecutors and the legislators -- that is their job …

At the end of the day, cops and law enforcement executives, their principal focus isn't the aftermath -- it's public safety, it's keeping people safe, it's keeping bad guys off the streets. And today as I'm sitting here talking to you, I don't disagree with that. I'm no different of a law and order person today than I was before. But if we're going to enforce laws … if we're going to create laws to better society, then we have to make sure that those laws are fair, that they're enforced, that the punishment fits the crime, and that -- most importantly -- that people sentenced to prison are not put there for draconian sentences.

And if you're going to lock people up for the lengths of time that we do, even for violent crime, you've got to do something to help them once they're inside. They've got to get an education, they have to learn respect, they have to learn discipline, they have to be given life improvement skills, and much of that stuff in the system that we have today is not done. And that's stuff that you don't see from the outside. You can only see it on the inside.

When you were the youngest warden in the country, how much interaction did you have with inmates there? Did you have the opportunity, in your mind, to have the kinds of conversations that you later had when you were there as an inmate?

No, you don't … The average length of stay at Rikers was 45 to 54 days … You're not keeping the same inmate population, there's a constant turnover …

Would you conduct yourself differently as a warden now? If you were in that role again?

Look, when I was at Rikers, I looked out for the inmates as much as I did staff … When I took over Rikers Island, an inmate going to see the medical staff could wait for four to six hours, which was completely insane, and I maneuvered those numbers to get the inmates into a clinic -- if they weren't seen within an hour, then there was some warden that was going to have a problem …

When I was being sentenced by my judge, an attorney that I don't even know, he called my lawyer and said, “Look I want to send a letter to the judge on behalf of Kerik” … He said, "All of a sudden Kerik came along and he found out that we were waiting to see these clients forever, he put a sign up basically saying: if you don't see your client in 45 minutes, call this number" … Basically that number was to my chief of staff … I looked out for the inmates' rights as best we could …

If I could do anything differently today, I think one of the things I would do is I would probably try to do something where there was more of a connection with their children. Because the most damaging thing that I saw, that I experienced firsthand in the system, was the devastation to the families and children, and the distance created between their fathers and children, which is really destructive … When you're on the inside, you get to sit in that visit room and … see these guys with their kids - it has a major impact on you.

What would a system look like that would “make people whole”?

At some point your constitutional rights and civil rights have to be given back to you in full. Today that doesn't happen. In some states you may be able to vote after a felony conviction; in many states you cannot … There's a laundry list of things that you cannot do as a convicted felon, you cannot have access to … Certain convictions, if you have a life insurance policy, you can't get that policy extended … Federal housing, federal programs, grants programs, educational programs, housing programs -- all of the things that these guys desperately need coming out of the system, many of them can't get. And many of these things last forever. Forever. It shouldn't be. If you've paid your debt to society, then at some point you have to scratch off that “convicted felon” thing. And it never happens.

I was with guys, these young military guys that did something stupid -- 19 years old, 18 years old, they're a convicted felon now … If the guy lives to be 110, the collateral damage to him and his family is going to last forever. Does that punishment fit the crime? No, it doesn't. It doesn't. And if anybody thinks that's good for society, they're completely delusional.

In your career, how many do you think you put in jail for nonviolent first-time drug offenses?

I couldn’t tell you. I was an undercover in narcotics. I bought drugs from a lot of people. I couldn’t tell you if they were first time. I would say probably 50 percent of them were nonviolent — no guns involved. Maybe 50 percent …

But I could tell you one thing: Nobody that I put in jail for selling me drugs in the state courts in New York, nobody went to jail for years on end. Nobody. There’s a big, big difference in state law and federal law …

If, as an undercover, somebody sells me five grams of cocaine, and they’re charged in New York state court, there’s a good chance that may be reduced to a misdemeanor possession [charge] if it’s a first-time offense. And results in a probationary sentence. In a federal court, selling to a federal agent, and tied into a conspiracy, that could be 10 years …

This goes right back to the sentencing guidelines …

The time you spent as police commissioner -- do you have regrets from that time [as NYPD commissioner]?

Do I have regrets?

Yeah, do you have regrets about how you ran the NYPD?

No. No.

Prior to you coming into office, the NYPD was in national news for the shooting of Amadou Diallo -- 41 times, unarmed -- and for the assault, the brutalizing, of Abner Louima. Those events, was it your view then, or is it your view now, that [they] reflected something about the approach or the culture of the NYPD?

As in what? The Amadou Diallo case, the cops that were charged in that case, they … went to court in a state trial. They were acquitted. They then went to court in a federal trial, and they were acquitted. They went before a departmental trial, and they were acquitted there as well. This all happened before me.

When I was police commissioner, that’s when their disciplinary ruling came down. And I basically said, you know, they, according to the law, to the law, they did not commit a crime. What happened was a tragic accident. And technically, under any other circumstance, they would have been given their guns and shields back and sent back to patrol.

I decided not to do that. And I didn’t do that -- not to punish them, but I honestly believe that based onwhat they’d gone through, based on the circumstances, it was probably not the right thing to do. I refused to give them their guns and shields. I assigned them to permanent inside desk jobs, and they went on with their careers from there … I couldn’t punish someone for something that a federal court, a state court and a departmental trial all said did not violate the law. So, there was nothing I could do.

Abner Louima, on the other hand, his circumstance, I think the violation of his rights — and the assault on him — I think it was atrocious, and anybody that doesn’t is -- I think they’re an idiot. The guy was assaulted. He was assaulted in a vile manner, and whoever assaulted him should have been held accountable, and I think they were.

The judicial decision [from Federal District Judge Shira Scheindlin] that concluded that the stop-and-frisk program has been run in a way that violates both the 14th Amendment and the Fourth Amendment -- do you agree with that?

I don’t know enough about the decision, or the case that was put before the court, because I was away at the time …

I do believe that stop-and-frisk — the authority for a cop to stop, question and frisk someone — is a tool to keeping the city safe. Now, it has to be monitored. There have to be rules and departmental policies on what that consists of, and how to track it and monitor it, and to ensure that it’s not abused. I think Bratton had a pretty good analogy when he said, it’s something like chemotherapy: put to good use it’s a good thing, you know; [if] abused it could be a bad thing. Well, it’s the same. I don’t feel any different than that.

I think it’s a necessary tool to keeping the streets safe, especially for cops that are in positions in very high crime areas, and their sole job in life is to go out and look for guns and bad guys, like the plain clothes anti-crime units in the city. If you tell those guys — those men and women — they can’t have, that they don’t have the authority anymore to do stop-and-frisk, then you should just put them back in uniform, sit them on a foot post somewhere, and let the guns and drugs and bad guys go rampant -- because you basically took their ability away to do their job. So, you have to make a decision somewhere. You have to call it like it is.

The reality is stop-and-frisk is a tool. But stop-and-frisk should not be abused, and it has to be monitored and watched by the department.

Do you believe it was abused in a widespread way?

I don’t know. I have no idea. I don’t know the case that was put before the court. I don’t know what they used to create that case. I don’t know any of the statistics. I know nothing about it.

The statistic that 6 percent of all stops resulted in an arrest, and 6 percent resulted in a summons -- is that concerning to you?

No. I can’t say it’s not concerning, because I can't - I don’t know enough about it … There is a bunch of stuff that people have to look at when they put these statistics together. You know, I remember we went through this in 2000, I believe, and people were saying, “Well, 25 percent of the population of New York City is black and Latino, and yet 75 percent of the people stopped are black and Latino, so there is a definite disparity” … But the reality is you’re not looking at the population. You can’t look at the population. If … you say, “Give me the description of the people that are suspects, based on those 9-1-1 calls,” those calls resulted in 75 to 80 percent of the calls being Bblack and Latino targets or suspects. Well, those numbers are a lot more compatible. Not to mention that the callers — that the victims of crime — 80 percent of the time were black and Latino as well …

The judge wrote … that the New York attorney general report in 1999 “placed the City on notice that stops and frisks were being conducted in a racially skewed manner” and “Nothing was done in response.” Is that a fair characterization?

No. That’s not a fair characterization … I don’t know about the 1999 report, but I do know in 2000 … I met with Eric Holder and Janet Reno about their concerns on stop-and-frisk, and we presented our case on what we were doing, and how we were doing it, and we also gave them access to an enormous amount of data — unlimited access to an enormous amount of data — that proved my point. And, basically, they said: OK, we got it. So there was no enforcement … They didn’t come in and sue us. They didn’t enforce a monitor on us …

This goes back to what I think would help today … A lot of it has to do with transparency, and that’s what I did back then in 2000 … I gave them access to everything we - to all the data we were collecting, number one. Number two, I put the actual stop-and-frisk information online … You could look at the crime in that precinct, and tell where the cops' enforcement was, and their enforcement activity.

The allegation from New York state Sen. Adams, that in a meeting Commissioner Kelly said he focused on blacks and Latinos “because he wanted to instill fear in them, every time they leave their home, they could be stopped by the police.” Are you disturbed by that?

I can’t answer for Kelly or Adams. That just sounds hard to believe to me, but I don’t know. I wasn’t there. I don’t know. I wouldn’t agree with it.

If you were running the NYPD now, are there ways you would approach the experience differently, having been on the inside?

Running the NYPD?

Yes.

If I was running the NYPD, I would change the way I operate? To change the police? No, that doesn’t make any sense - say it again?

You mentioned other aspects of the criminal justice system that you would like to see changed. If you were running the NYPD, are there ways that you would run the NYPD differently based on the experiences that you’ve had since being on the inside?

No. You asked me this before. I don’t think I would do anything differently. You run the oversight of the NYPD, the executive management of the NYPD; the mission statement of the NYPD is to serve the public of New York and keep them safe and secure. And that’s what their job is. They don’t control the prison system. They don’t institute laws. They don’t create legislation. They don’t - they do none of that. The substantial part of our criminal justice system that is in need of repair has a lot to do with legislators, has a lot to do with the overall criminal justice system and the prison system. But how the cops operate on a daily basis -- one, they have to abide by the law. They have to abide by the law of internal policies. They have to have the resources. They need to do their job, and they need to have support by the upper management — to make sure that they have the support necessary to do that job. So, one has nothing to do with the other. Unless the police commissioner is going to, in some way, would advocate for some things within the system -- which, if I took over the NYPD tomorrow, I’d still be advocating for the stuff I am on the criminal justice system. So that would be perhaps a difference. That’s it.

Do you see a turning point coming in terms of criminal justice policy?

Honestly, Josh, I don’t know. I’ve seen a lot of changes. I’m hearing about a lot of changes in the state systems …

If Texas can change, and start instituting alternative sentences to incarceration, if Texas can start giving back your civil and constitutional rights post-conviction, post-your punishment … If Texas can do that, then it can be done anywhere …

In the federal system, I don’t know if there is a clear-cut turning point at this point today. I hope it’s coming. You know I’m praying that people will listen. I think the states don’t have a choice because it’s economics ... A governor can’t say, “We’re going to continue to lock people up regardless of whatever,” because eventually he’ll run out of money. In the federal system, they don’t seem to have that problem …

There has been no reduction at all in the federal prison system. None. Not one year.

Which, you have to wonder how that’s possible. And you also have to wonder: At what point does it just erupt and explode? Because it’s unsustainable the way it’s going …

When you say “erupt and explode,” what do you mean?

It will overwhelm the system … If you look statistically at black men being arrested and incarcerated over the last 30 years, say … If we continue to arrest and incarcerate black men at that same percentile increase, I would bet that 70 to 75 percent of every black man in this country is going to be in prison 30 years from now. I’m no mathematician, and I’m no genius. But you cannot sustain the numbers — the population, the economics — of what we’re doing. You can’t.

It just costs way, way too much -- that’s on a financial basis. The collateral costs — the collateral damage to families, to children, to society as a whole — is just overwhelming. And I don’t think anybody gets it until you actually sit down to look at it.

Shares