I’m a huge sports fan. My fandom often — as in the case of collegiate athletics, a deeply exploitative enterprise — contradicts my political commitments, but I’m a sucker for the grace and ferocity of organized competition. Sporting events involving national teams are particularly irresistible, not only for the competition itself, but for the lack of provincial limitations (as with American football) and the added drama of international affairs.

I am an adamant critic of American foreign policy and the dangers of compulsive patriotism, but I root heartily for teams from the United States, for the same reason I root for the Oklahoma Sooners (from where I earned my doctorate) — not as an endorsement of institutional practice, but as somebody invested in place and community and thus in the outcome of the games I watch.

Though not a devotee of winter Olympics (I find the summer incarnation more compelling, possibly because I detest temperatures below 70), I casually follow them, and, like many Americans, veg out to the opening ceremonies. I found them especially annoying this year.

They’re always at least slightly irritating, what with monotonous announcers (corporate stooges, essentially) offering scripted comments about costumes and competitors along with mind-numbing cultural trivia. When the comments venture into geopolitics, as they always do, they become unbearable. In these moments we’re forced to contemplate at what point fandom is conflated with nationalism.

There is acute beauty in watching humans operate with the physical skill and technical mastery of Olympians. Even on our couches, munching on chips, dip and carrot sticks, we vicariously experience the excruciating and joyful emotions of athletic transaction. There can be tremendous compassion and dignity in competition. For me, that beauty always defeats the buffoonish ephemera of the networks and their sponsors.

Competition, like every human endeavor, is inherently political, but there is a distinct politics of airing sporting events that need not exist. It was on display during Sochi’s opening ceremonies when David Remnick, possibly in a fruitless attempt to be less boring, offered a procession of Orientalist clichés and pious bromides about Russia’s isolation from the Renaissance. (I’m pretty sure not even Remnick knew what he was trying to say.)

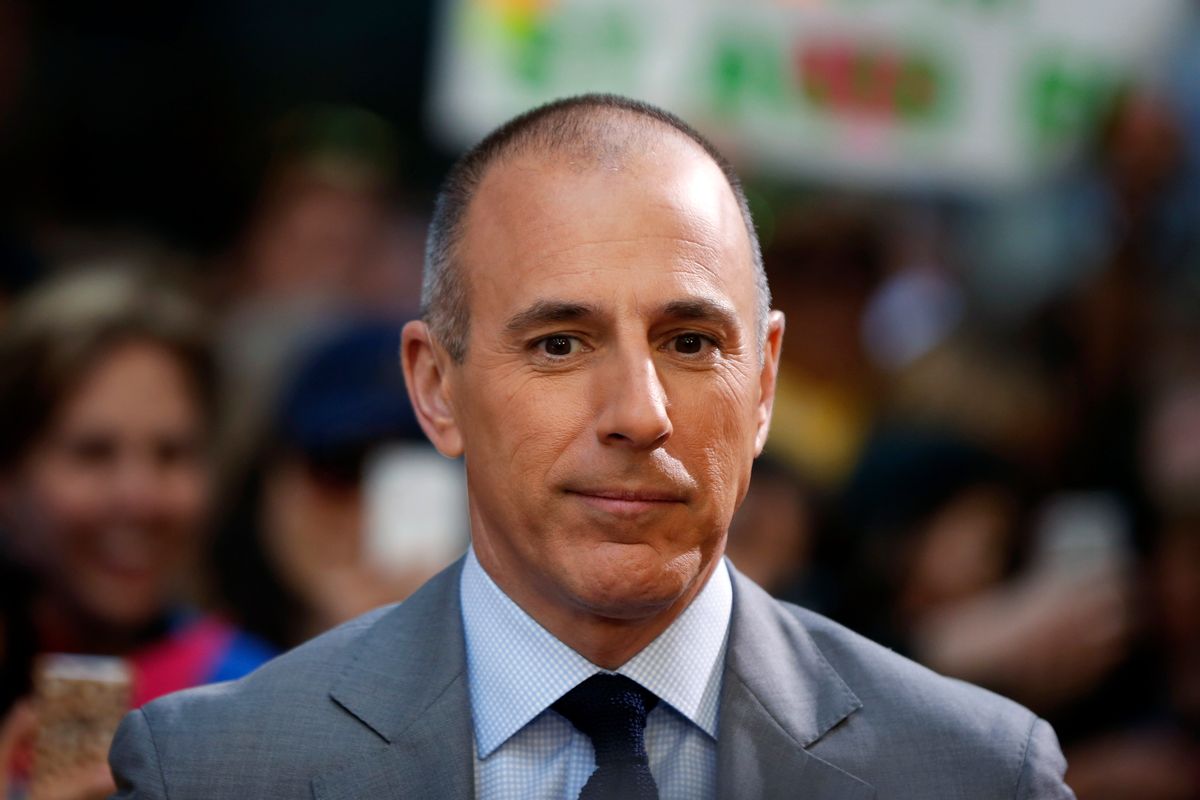

NBC actually took a beating in the press for not being political enough. Beyond the fact that the mere thought of Matt Lauer and Meredith Vieira discussing anything more substantial than the Russian propensity to dream is enough to exhume Howard Cosell’s corpse and let it handle the commenting duties, the demand that NBC highlight Russia’s dismal human rights record is ridiculous.

The demand isn’t ridiculous on its face. I’m all for conscientious or even subversive commentary. It would make sports more interesting and highlight the disconnect between athletic mores and state violence. I simply want that commentary to be handled consistently.

The same folks upbraiding NBC for supposedly downplaying Russia’s shortcomings would choke on their outrage if, during an international competition hosted by the United States, the announcers condemned Guantánamo, NSA spying, drones, police violence, racist jurisprudence, environmental destruction, corporate malfeasance, and the other abuses that put moralists in no position to so intrepidly direct their outrage elsewhere.

At the Salt Lake City games in 2002, quite the opposite happened. Not only did the coverage lionize the host country with all the grandeur of big-budget ostentation, it included a lengthy tribute to 9/11.

Consider the context. All countries commemorate tragedy, but it’s not common practice at an Olympics opening ceremony. The 9/11 tribute, then, reinforced the tacit notion that American suffering, like American democracy, is exceptional, more worthy of memorialization that whatever suffering has befallen other nations (some of it, incidentally, instigated by the United States).

Perhaps organizers of the games conceptualized 9/11 as a tragedy of global proportions, worthy of tribute for an international audience. It seems like an innocuous sentiment, but in reality the memorialization of American tragedy in the absence of critical scrutiny nurtures a slovenly, mechanical commitment to age-old mythologies of U.S. exceptionalism.

Either way, the time spent mourning the anguished innocence (and thus timeless nobility) of the United States left no space for the sort of human rights sloganeering that talking heads demand when China or Russia hosts the Olympics. (Just wait until the Qatar World Cup in 2022 for the real fun to begin.)

This is nationalism in its basest form. It is dull, banal and entirely predictable. And it permeates American sports culture.

I hate my sports mixed with jingoism, but it’s the only way to get them these days in the United States. To be sure, this isn’t exclusively an American problem, but I’m an American viewer watching American television, so it’s my problem, whether I want it to be or not. The sanitization of American politics in sport, like the celebration of militarism, illuminates the profound connection between corporate sponsorship and plutocratic governance.

When I watch American Olympians, I’m not rooting for Obama or democratic values or victory in whatever third-world country we’ve invaded; I’m rooting for the athletes with whom I share a nationality, in appreciation of their devotion and dexterity. Besides, I rarely know the viewpoints of the athletes of any country. It’s stupid to conflate citizenship with state praxis.

Of course, athletes sometimes enter into, or create, political conversation. When they do, it reinforces the nationalistic discourses that frame Olympics coverage in the United States. Conservatives like Tim Tebow, Peyton Manning, Jack Nicklaus and Jeff Gordon (and coaches like Mike Kryzyzewski) enjoy adoration, often without the burden of being named as “political” in the first place.

On the other hand, the list of dissenters to suffer the smug scorn of snazzy sportscasters is long and distinguished, from Jack Johnson and Paul Robeson to Bill Russell and Carlos Delgado. In the 1968 Mexico City summer Olympics, Tommie Smith and John Carlos raised their fists in solidarity with the black and poor; they were thoroughly ostracized by the American press and promptly vanquished from the Olympic village.

If you are an athlete, don’t even consider sitting out the national anthem — which needs to be played at every sporting event at every level why exactly? — unless you’re willing to be condemned as a disgrace. The point here isn’t whether it’s appropriate or not to shun the anthem. The point is that conscripted fealty to national symbols undermines the quixotic myth of the dispassionate sporting event. The ostensibly apolitical arena of sport is in fact thoroughly beholden to the politics of patriotic reverence.

Whenever an athlete challenges nationalistic commonplaces, we are treated to priggish declarations that politicizing sport is a moral crime. Yet the unexamined norms of sport are incessantly political, often difficult to spot because patriotic reverence sells itself as universal.

Network executives are perfectly happy interjecting politics into sport, but the right kind of politics, the ones assuring us that introspection is an activity relevant only to the uncivilized regions of the world.

Shares