Traditional animation is on its way out. In the age of Pixar, Dreamworks and other big-budget production companies that specialize in children’s entertainment, technology trumps tradition. There’s something exemplary about 3-D animation, something that fits in with contemporary culture in our desire to render magic real. We want to feel like we’re inside the same room as the characters we watch on the screen, even, oddly, when it comes to representational entertainment, like cartoons. In the age of hyperrealism, fantasy worlds must blend with our own, and imagination takes a back seat to spectacle.

So animation studios on the technological forefront release features that do away with traditional photo film. With digital production techniques at the ready, movies can now be counted on to remain unblemished throughout time. And why shouldn’t they be? What better way to fend off ennui than to develop newer, cleaner ways to melt the eyes? That which does not evolve fades from relevance, yes? Well … perhaps not entirely. There is one famous animator who rebukes modern technology in favor of hand-drawn, 2-D conventions. His grumpiness knows no bounds, and he seems to be interested more sometimes in what will perish than what will live on. But in many ways, even at Pixar where the future of the industry is being assembled brick by brick, he is looked to as a constant source of authenticity and inspiration.

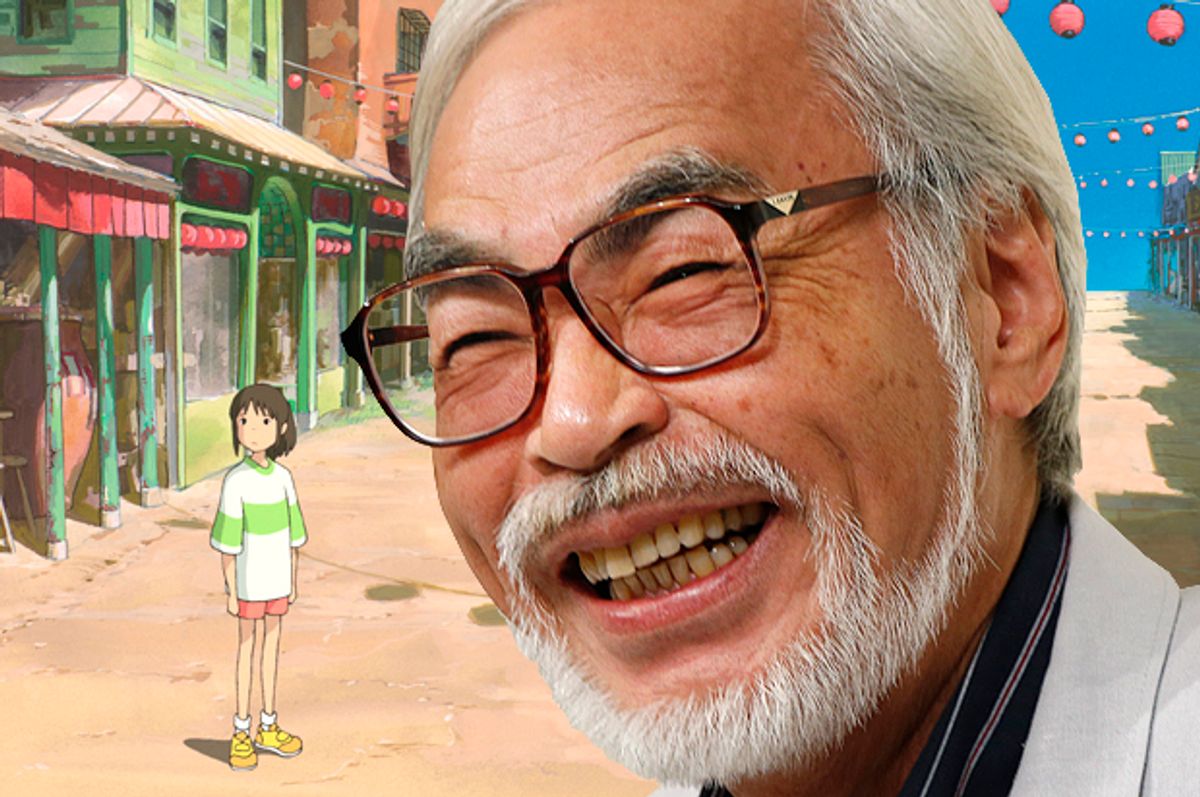

It is not easy to write about Japanese animator Hayao Miyazaki, founder of the creative powerhouse Studio Ghibli, without relying on intense speculation. Those who have met the man, such as Roger Ebert, for instance, who was able to secure a rare interview, have found themselves wading through a morass of eccentricities. His dislike of the public sphere is clear, and as of the last decade he seems to pine for the end of all creative media, including animation itself, in favor of a society that works in accordance with the natural world. From his hard-line environmentalism and anti-Fabian leanings to comparing, in July of 2010, the act of using an iPad to public masturbation, he has painted himself as a Luddite with rigorous creative standards that have resulted, ironically, in his becoming an entertainment icon.

Born in 1941, the year of Pearl Harbor, Miyazaki grew up with a sick mother who would go on to defy all those she knew by living to a ripe old age. It is perhaps because of her that a preoccupation with strong women would appear throughout the director’s work. His repertoire features a deluge of feminist themes that range from the ideal to the pragmatic. From the unadorned heroics of Kiki, girl witch and main character in “Kiki’s Delivery Service,” to the feral "wolf girl" San of “Princess Mononoke,” the girls and women of Miyazaki’s imagination are forced to rely upon themselves, and rarely if ever turn to men to ensure their safety.

There is something endlessly fascinating about Miyazaki’s approach to animation. He has come to be known as the Walt Disney of Japan over the years, not only due to the immense popularity of his films at home (and to a lesser but devoted extent, abroad), but their overarching wholesomeness. Save for some notable exceptions, the majority of Miyazaki’s films (“Ponyo,” “Howl’s Moving Castle” and “My Neighbor Totoro,” to name a few) are geared toward a younger audience; and like Disney, his story lines contain a kind of moralism.

But the Disney comparison pretty much ends there. The name of his studio, “Ghibli,” comes from a Libyan word used to describe Mediterranean winds coming over the Sahara that Italian fighter pilots encountered in WWII. Miyazaki, as one can easily see from watching any of his films, is absolutely obsessed with the concept of flight, and his work reflects a certain longing to be free of the forces of gravity. He doesn’t seem overly thrilled with the state of the modern world, whether in terms of how humans treat the environment or how they covet resources. Though commercialism has certainly given the studio the means to produce some of its most ambitious projects, the proliferation of Totoro merchandise doesn’t really measure up to Disney's corporate fiefdom. In some ways this is because Miyazaki’s work can seem so odd and mature outside of Japan. But it's also a matter of personal choice.

The Ghibli museum in Tokyo is filled with attractions geared toward children, though ones that don’t rely on rides and mountains of merchandise you’re sure to find in Disney theme parks. Its design is influenced by European — particularly Italian hilltop — architecture (many of Miyazaki’s films evoke an idyllic Europe that exists as if World War II never occurred), three-dimensional zoetropes, mock-animation studios, and actual re-creations of popular characters such as the cat bus from “My Neighbor Totoro,” within which children can walk around. In what is perhaps the addition most telling of the director’s personality, however, the museum features a small theater with shades that lower before the showing of films, and rise when they finish. The reason for this is Miyazaki’s insistence that children can become afraid when sitting in dark theaters, and have a natural need to interact with sunlight. In this small theater he also made sure to use traditional film equipment, reel and all, as opposed to digital, noting that he wants children to understand the inner workings of the technology itself so that they don’t take it for granted.

Miyazaki is also aesthetically drawn to the idea of aging. Or perhaps it would be more accurate to say that he appears to embrace and encourage an acceptance of the natural cycles of life and death. You could find such themes running through most of his films, particularly “Princess Mononoke” and “Nausicaa of the Valley of the Wind,” but even the way he designs his public attractions seem to share in the message. The man, sometimes referred to as childlike himself by colleagues, approaches his target demographic with a mixture of psychological realism and what can only be referred to as magic. Although the Disney comparison holds up on the surface, it disintegrates beneath.

The director treats his films with far more psychological complexity. Though he emulates some of the stylistic elements of Disney animation, he shies away from conventional storytelling associated with it. The majority of classic (and even some modern) Disney films rely upon classical tropes. Villains are evil to the point of mustache-twirling, and must be foiled. True love is the secret to redemption. Damsels are in distress and handsome men are always ready to fight their battles. Though things have certainly matured in recent years, Disney has historically allied itself with the cultural mainstream.

When it does take risks, particularly at subsidiary Pixar with films like “Wall-E,” “Brave” and “The Incredibles,” all of which hold their own in terms of innovation, the majority of what the industry produces are human- (or humanoid-) centric. In a Disney film, it’s the happiness of the main characters when the credits role that determines their success. In order to have a happy ending, that character must conquer the obstacles in his/her path, and while larger themes are certainly explored in the meantime, society itself remains mostly unchallenged. Miyazaki, however, while gentle, takes an entirely different approach. His films depict worlds in which nature in particular is more important than humans themselves.

* * *

It might even be said that there’s a certain amount of anarchism associated with Miyazaki’s outlook, which, when considering his work as a children’s animator, can come off as discomfiting. In a brilliant 2005 New Yorker article on Miyazaki by Margaret Talbot, the director, excited about the idea of environmental and/or societal collapse, is quoted as saying: “I’m hoping I’ll live another thirty years. I want to see the sea rise over Tokyo and the NTV tower become an island. I’d like to see Manhattan underwater. I’d like to see when the human population plummets and there are no more high-rises, because nobody’s buying them. I’m excited about that. Money and desire — all that is going to collapse, and wild green grasses are going to take over.” Depending on how much you already know about Miyazaki, such statements might not come as a surprise. He has become increasingly enthralled over the years with the possibility that, soon enough, humans will have exhausted their dominion over planet Earth. If you glaze over subtler aspects of films like “My Neighbor Totoro” or “Ponyo,” his ideas might not seem as apparent, you might not suspect his motives. But in films like” Princess Mononoke” or “Nausicaa of the Valley of the Wind,” they are on clear display. According to Miyazaki we have overstayed our welcome on Earth, and nature will find a way of fighting back.

“Nausicaa,” while not having quite as much of a cultural impact outside of Japan, perhaps encapsulates most plainly the director’s radical worldview. The film was released in 1984 and had a bit of a rough ride on its way to screen. Though the director originally pitched the script on its own as a film, it was turned down. But it eventually became one of Miyazaki’s most thrilling and morally complex works: “Nausicaa” tells the story of a world in which small groups of humans live in sparse safe-zones on the outskirts of a poison forest. Life is difficult, birthrates are low, and Nausicaa, the main character, is the warrior princess of a small, yet proud township known as the Valley of the Wind, due to its reliance on air currents to drive energy production. Her character and her people are reverent of the poison forest, and the gigantic insect creatures that inhabit them, known as Ommu. Nausicaa learns that poison forest was actually brought about by human beings who wished to purge the land of pollution. Her effort to uncover the truth culminates in the revival of a gigantic creature called the God Warrior, and the revelation that scientists predicted the end of days, and thus altered human genes so they could interact with the ecology they’d go on to alter. At the end of the series, Nausicaa ends up destroying all the traces of humanity’s technological archives (stored in a structure known as the crypt), deciding that what came before the end of the world is wholly worthless, and an entirely new paradigm is required to ensure a better future.

So Miyazaki’s most ambitious creation, which made its way to film in 1984 in a largely truncated version of the comic’s events, romanticized the notion that all of human progress is a fallacy, and that redemption will come not from making changes in the present, but pressing the reset button so that we forget it all happened in the first place. There’s really nothing Disney about that.

But what makes Miyazaki truly subversive is that at the conclusion of all Miyazaki films, regardless of his disdain for modern life and technology, all of his melancholy is counterbalanced by sincerity and warmth. Miyazaki, while sometimes coming off as stubborn, does not shove his way into the spotlight. Perhaps that is one of the reasons millions perceive the director’s films to be beacons of hope, even if he himself can’t share in the feeling. Miyazaki doesn’t seem to want to choose what we, as viewers, should think about reality. He wants us, and children in particular, to be able to decide on our own.

Though films like “Porco Rosso,” for instance, the mythological story of an Italian airplane pilot who turns into a pig (Miyazaki, noting the anatomical similarities between pigs and humans, retains affinity — and even admiration — for the creatures), might feature lofty lines like, “I’d rather be a pig than a fascist,” films like “My Neighbor Totoro” and “Spirited Away” promote the need for children to incorporate magical thinking in order to overcome psychological afflictions. It’s this strange mixture of doom and beauty that render Miyazaki’s oeuvre so unique. One cannot help being drawn to work that allow you to understand the complexity of the questions it raises — and simultaneously revel in the impossible beauty of simple answers.

Perhaps this is why it was especially difficult for many, me included, when, just this last year, Miyazaki gave notice that he would be retiring. The announcement came alongside the release of his controversial swan song, “The Wind Rises,” which tells the story of Jiro Horikoshi, the famed aeronautical engineer who created the Mitsubishi A6M Zero Fighter. The film generated a great deal of buzz in Japan and Korea specifically on both the political left and right, not only for its lack of magic, its thematic maturity and faithful historicity, but for the fact that it glorifies the relationship between Japan’s primary machine of aerial combat during WWII and its creator, a young man obsessed with flight. Much like the director himself. Miyazaki, who could never be pegged for an advocate of any sort of warfare, seems more interested in what causes people to create, as opposed to what is done with their creations. Flight reigns supreme in his vast, beautiful universe, and humans would be better to soar above the clouds than spend their time worrying at their feet.

After Miyazaki announced retirement, millions of fans all over the world gave a collective sigh. Though perhaps, like all of Miyazaki’s decisions, we will soon be led to transform our sadness into hope. Recently, the director announced that he is working on a new comic, the first since “Nausicaa of the Valley of the Wind.” A warring states samurai manga, it seems as if to Miyazaki the word "retirement" itself might be subject to redefinition. One can never be too careful with a man whose work seems to exist in part to defy expectations.

Shares