Personhood lost big during the 2014 midterms because personhood tends to lose big every time it's put on the ballot. Whereas politicians have gotten relatively savvy at couching antiabortion legislation in the language of safety and women's health, they've had less success at explaining why they think fertilized eggs, embryos and fetuses should have full legal rights.

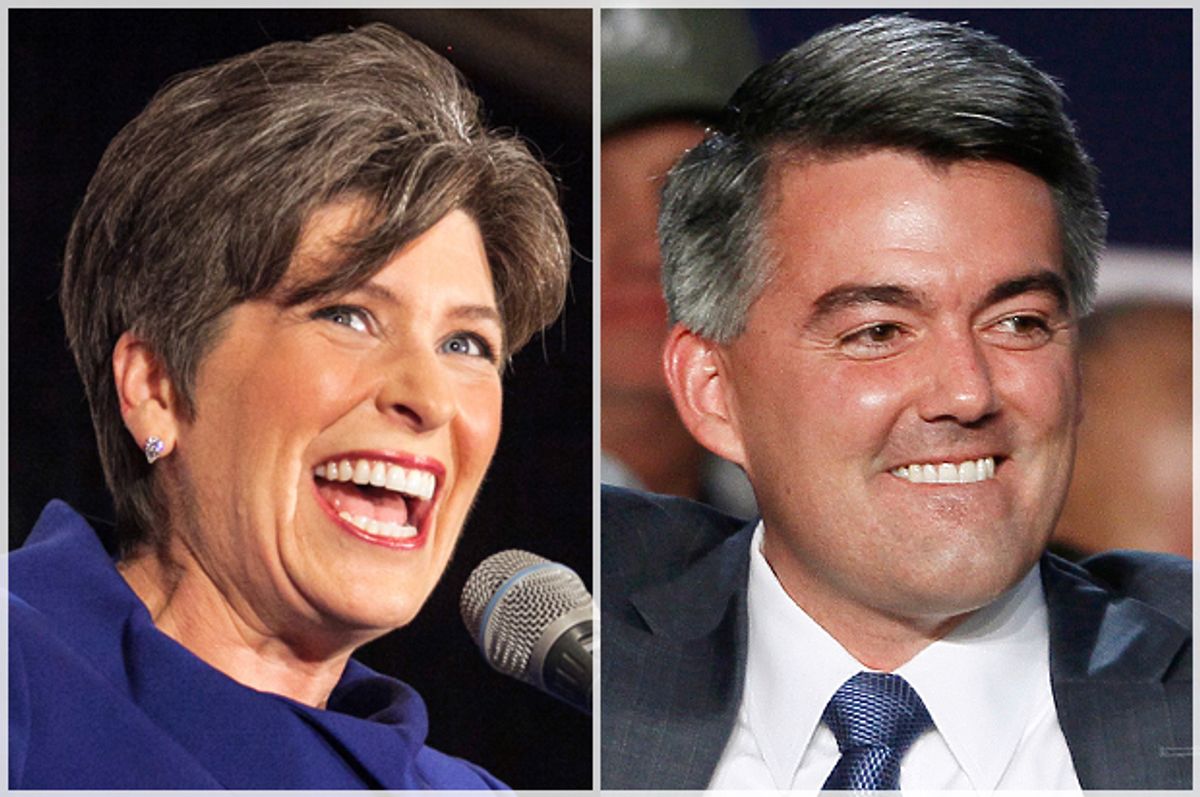

This is why you saw a lot of politicians running away from personhood in 2014. In Colorado, senator-elect Cory Gardner tried to downplay his record by claiming a change of heart. During her own campaign, Iowa's senator-elect Joni Ernst argued that her support for personhood is personal and largely theoretical. Even the Susan B. Anthony List, a lobbying group that supports antiabortion candidates, wouldn't touch personhood during the midterms. Not because they don't support it (they do), but because the group recognized that it was politically toxic.

Which has left leaders in the personhood movement taking stock and recalibrating for the next cycle. In a piece that ran last week on LifeSiteNews, Gualberto Garcia Jones, the national policy director for the Personhood Alliance, said the movement won't be backing down on the issue, but might be shifting its focus from statewide ballot initiatives to smaller, local efforts:

When you look at electoral maps of the country, it is readily evident that majorities in almost every metropolitan area of the country are opposed to our worldview. These metropolitan areas are also the major media centers and accumulate large percentages of the voting population in every state. [...] We need to start engaging in more asymmetrical tactics, and this means engaging the enemy in municipalities and counties that we know we control.

This can be done at the legislative and political level, as Georgia Right to Life and other groups have done by the endorsement of state officials, or it can be done by engaging in municipal ballot measures.

Local laws deal with many powers that touch upon the personhood of the preborn, from local health and building codes to local law enforcement such as child abuse prevention. It is time to establish the recognition of universal human personhood into these laws.

But the strategy of working personhood into existing law isn't exactly new for the movement. In fact, a number of seemingly unrelated laws have been used to establish separate rights for embryos and fetuses, and earlier this year, Tennessee became the first state in the nation to pass a law criminalizing women for their pregnancy outcomes. These policies may not be branded as personhood in the same way as recent ballot initiatives, but the rationale and outcomes are largely the same.

In the New York Times this weekend, Lynn Paltrow, executive director of National Advocates for Pregnant Women, and Jeanne Flavin, a sociology professor at Fordham University, wrote about the antiabortion and so-called "fetal harm" laws that have already been used to criminalize and jail pregnant women across the country:

Based on the belief that he had an obligation to give a fetus a chance for life, a judge in Washington, D.C., ordered a critically ill 27-year-old woman who was 26 weeks pregnant to undergo a cesarean section, which he understood might kill her. Neither the woman nor her baby survived.

In Iowa, a pregnant woman who fell down a flight of stairs was reported to the police after seeking help at a hospital. She was arrested for “attempted fetal homicide.”

In Utah, a woman gave birth to twins; one was stillborn. Health care providers believed that the stillbirth was the result of the woman’s decision to delay having a cesarean. She was arrested on charges of fetal homicide.

According to data from National Advocates for Pregnant Women, there have been 380 cases in which a woman's pregnancy played a role in her arrest or detention since 2005. In the years between 1973 and 2005, the organization documented 413 others. All of this has happened in the absence of legal personhood, and there are new arrests and forced interventions every month. And as Paltrow and Flavin pointed out, talking about personhood only as it relates to access to abortion and contraception erases what current laws have already done to strip pregnant women of their own personhood.

In addition to outlining his recommendations for the personhood movement's strategy moving forward, Garcia Jones also spells out the mission that drive its activism:

Personhood looked at the undue burden test [established in Planned Parenthood v. Casey] test and responded emphatically that not only do we want to create an undue burden, but we demand the total abolition of abortion. We never believed that this would be achieved through an easy Supreme Court victory. Instead, our goal was to increase the social tension. In other words, we looked at the temporary reverses, at the ballot box and legally, as ways of increasing the social tension on the road to abolition.

Compare this to how Gardner and Ernst explained their support for personhood. Or how Rand Paul, a likely Republican presidential candidate in 2016 and the sponsor of a federal personhood amendment, has explained his own. Paul has laughed off suggestions that the Republican party wants to ban birth control while supporting an amendment that could effectively do just that. (His anti-criminalization agenda also doesn't mesh well with a personhood amendment that could jail women for miscarriages.) Ernst hails from a state that used the rationale of personhood to jail a pregnant woman for going to the hospital after she fell down a flight of stairs, but calls her support for personhood a matter of personal belief that doesn't have immediate policy ramifications.

Personhood is already shaping policy and having an impact on the lives of women across the country. The ballot initiatives on personhood may have failed, but the movement behind them isn't going anywhere. It's just recalibrating.

Shares