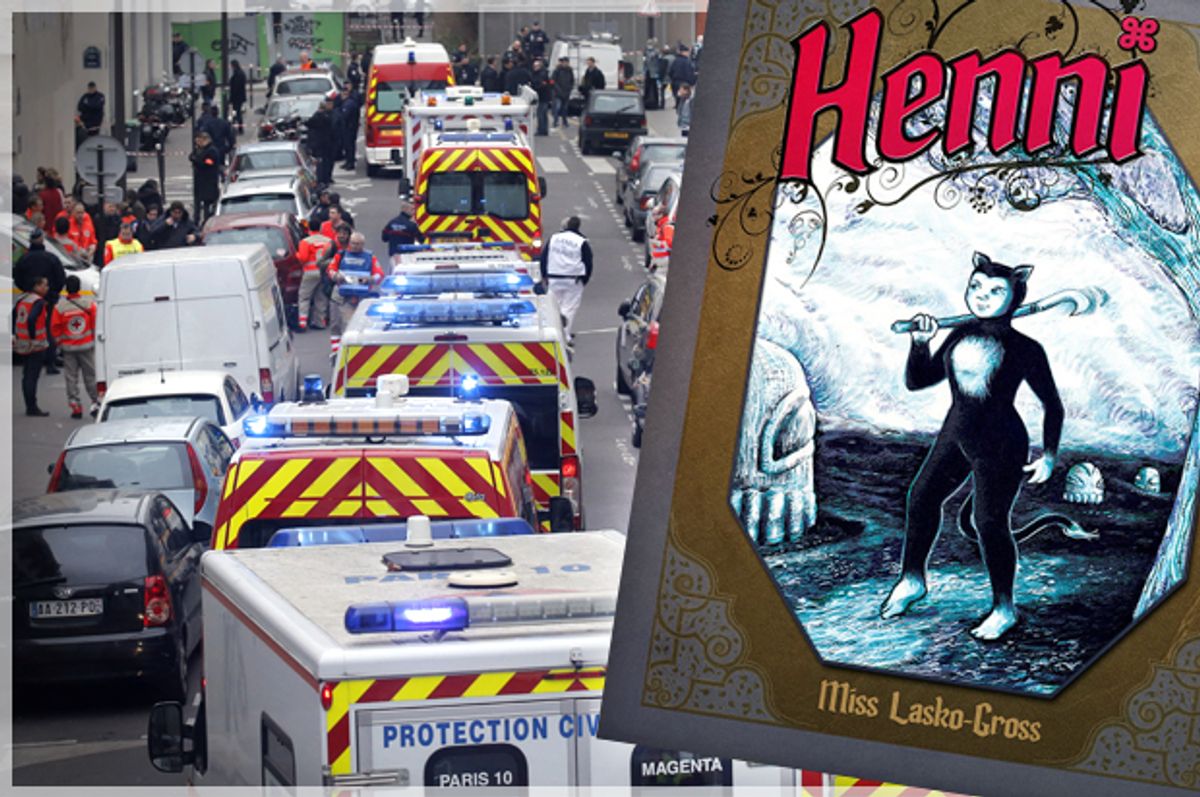

Though I don’t think we’ll be able to assess its full effect for years, Wednesday’s Charlie Hebdo massacre has already provoked a worldwide response. Most of that response has been defiant, some of it has been apologetic. Some of the defiance will, as is typical since Salman Rushdie found himself facing down a Fatwa, trickle into apologetics as the days go on, and those accustomed to defending the acts of idiopathic murderers will continue to do so by maintaining that, although terrorism isn’t a perfectly legitimate form of critique, the deaths of the cartoonists was deserved, excusable, a consequence of foreign intervention or cultural insensitivity, of institutional hatred that, ultimately, results from the scourge of Western hegemony and its decadence, its arrogance, its particularism. The dance of provocation thus continues, and meanwhile, a frothing cauldron of fear is fermented, a witch’s brew that billows poison into our eyes, distorts our perspectives and makes our nerves twitch. Our imaginations have the most to lose, as the prospect of being harmed physically for ideas, good ideas or bad, is the rough equivalent of an adult bloodying a child’s nose for wondering at the makeup of the stars.

Recently, I read a particularly powerful book by Miss Lasko Gross, a graphic novel by the name of "Henni." Cartoonists like Gross have, like many (particularly American) cartoonists, existed for years on the artistic fringe. In France, comics are referred to as the "Ninth Art" and, like in other European countries and Japan, are seen as far more legitimate as an art form than here in the United States, where superheroes, fantastic as they are, are what popularly come to mind when people think of comics. But comics and graphic novels are in reality a far more expressive, varietal and subversive medium than many understand. One might recall cartoonists like Art Spiegelman in that regard, specifically pertaining to books like "In the Shadow of No Towers" and "Maus," both of which have tackled political material in an artful, if ruthless manner. Underground comics, often referred to as Comix, which Spiegleman himself cut his teeth on, in particular revel in the grotesque, the political and the profane. One need only read Robert Crumb to understand the sometimes displeasing lengths cartoonists have gone to in response to censorship or the arbitration of taste. Though some comics, like Crumb’s, for example, are distasteful, grotesque or offensive, and many other modern cartoonists produce edgier and arguably more meaningful work, they also serve a purpose: to ensure that no one can exert control over the grotesque. The human mind can be a dirty, destructive and violent entity; to attempt to fit its creative output into categories, into set axioms that are meant to please an inchoate religious or political whim, is not only abhorrent. It’s impossible. The only way to temper the output of the free mind is to put an end to it, as the nihilist gunmen in Paris have shown us in their mad attempt to anesthetize culture.

Despite the fact that Miss Lasko Gross has been working in underground comics for years, "Henni" has been receiving popular attention for its ambition and themes, themes that seem fatefully, and unhappily, relevant in relation to what happened in Paris on Wednesday. As the news came out and the horrors of the situation at Charlie Hebdo revealed themselves, I found myself thinking back to the book again and again. The art style is fantastical and somewhat grotesque, an homage, it seems, to Maurice Sendak. Though the story is far more adult than "Where the Wild Things Are." "Henni" tells the tale of a young girl, a humanoid cat creature by the title name, as she is oppressed repeatedly by various kinds of religious philistines, all of whom happen to be men. It’s a story that champions feminism and advocates a supreme distaste for religious extremism of all kinds. It’s impossible while reading "Henni" not to notice the parallels between the bearded mendicants keeping the protagonist in her box and modern religious extremists, men who continually murder freedom of expression with ideological weed killers, attempting to turn the creative landscape into scorched, dead earth upon which artifice can be built. "Henni" revels in the possibility that, although the pen is mightier than the sword, the one holding the pen can be urged toward conformity. That in a society where creativity is limited, art cannot truly exist.

"Henni" seems particularly relevant now, being that the men and women killed in Paris were people who have spent their lives making cartoons. It doesn’t matter much whether they were good cartoons or bad cartoons; they were, in fact, like most things, a mixture of the two. What matters is that they were designed to challenge the very destructiveness that came, wild-eyed and depraved, to their front door. In "Henni," the world the main character inhabits might as well double as a cage. To challenge society, to challenge religion, to challenge gender roles or political sensitivities is seen as blasphemy across the board. What frightened me while reading "Henni" is that that world -- the barren, devalued landscape of arid ideology -- could very well become our own. Cartoonists value their work for many reasons, but one of those reasons is that, to make comics, you naturally accept that your work can and will be designed to offend, that to keep within set paradigms, to refrain from exaggeration and sophistry and peevishness, is antithetical to what it means to keep culture vital. The outpouring of solidarity from cartoonists the world over, many of whom are drafting powerful protest cartoons or taking selfies with their pens and pencils, show that the medium is a family business, and expression is not to be trifled with. To those who would defend the murderers of such people, I would ask what kind of world they envision. Is it the type of world they would want to live in? Or is it the type of world they would be forced to live in? The type of world where meekness gives way to fallow art, and a litmus test of trigger words decides what we consume?

The Charlie Hebdo massacre, if anything, should remind us that it isn’t just the presence of offensive ideas that is terrifying to some people. It is the presence of ideas themselves. Charlie Hebdo reveled in exaggeration; it made people cringe. Cringing can be uncomfortable, but to never be uncomfortable is to exist in a state of crazed ignorance and fear. It doesn’t mean that everything that offends us is necessarily authentic, but it does mean that what offends us should be protected. And until we begin to realize that, we’ll be in danger of losing our most important human aspect: perspective.

In the coming days, I expect that heels will dig in and a litany of essays will be written to attempt to trivialize the lives of those killed for the sake of political gain. But I hope that, off the Internet, away from the headlines and in our houses and heads, we’ll defy fascism and repeat to ourselves: Je Suis Charlie. Even, of course, if we are not Charlie. For unlike the poor souls being laid to rest, we are still alive.

Shares