President Obama’s speech in Selma, Alabama, this past weekend on the 50th anniversary of Bloody Sunday was one for the history books. Despite my general lack of enthusiasm for liberal politics these days, his challenge to us in this nation to do the hard work of becoming the very best version of our collective selves that we can be still touches every liberal impulse I have. Sometimes, I aspire to cynicism but I never quite make it. I would be disappointed far less if I could.

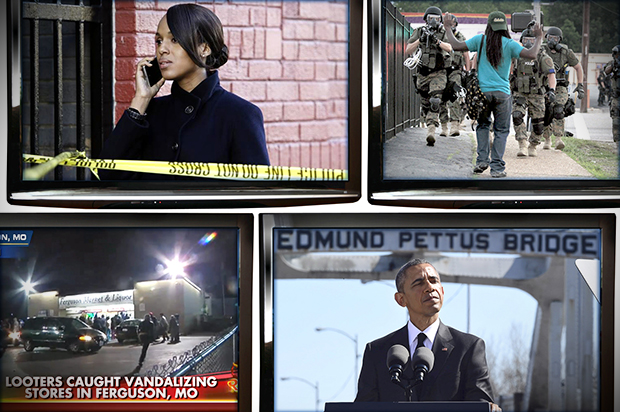

In his remarks, Obama did some of the most forthright truth telling that he has done on race relations in his six years in the White House. Standing at the base of the Edmund Pettus Bridge, he rejected the notion that nothing had changed in 50 years, that no progress had been made. But for a generation of us confronting the rollback of Voting Rights laws and the killings of young Black men every time we turn around, it is not entirely clear to us whether the long awaited change has come. To this generation, the president had to concede that though 50 years had brought to us Rep. John Lewis in Congress and Obama himself in the Oval Office, it also found us staring down the pages of the Justice Department’s damning new report on overt racial discrimination in Ferguson, Missouri. For any who hoped to call the practices in Ferguson an isolated incident, the president invited them to “look around” and draw another conclusion.

Given how much virulent right-wing language policing has hobbled racial discourse in this country, particularly from our first Black president, admitting that the events in Ferguson are not isolated is a hugely important intervention.

The report itself pulled no punches. It noted that “Ferguson’s law enforcement practices are shaped by the City’s focus on revenue rather than by public safety needs.” Moreover, “police and municipal court practices both reflect and exacerbate existing racial bias, including racial stereotypes.” The data demonstrated that clear racial disparities mostly impacted African-Americans, and perhaps most damning of all, “the evidence shows that discriminatory intent is part of the reason for the disparities.”

Racial intent is the hardest thing to account for in current conversations on racism. Even when racial disparity is present it is frequently difficult to prove racist intent, and racial apologists often point to this lack of proof of intent to dismiss any charges of racism. But this report does not just hang its hat on the question of racial disparities, which, frankly, matter greatly in combating racism. Through conversations with citizens, police officers and city officials, including scrutiny of emails that said blatantly racist things about Black people, the report shows an appreciable level of intentional bias.

“Our march is not yet finished,” the president said repeatedly on Saturday.

This is true, and yet, I wonder if we have the capacity to be the America that we have marched for. Do we really want to become a place where African-Americans are not viewed as a form of consistent revenue generation for municipalities that refuse to raise sufficient tax revenue? I ask because we have always seen Black people as a form of national revenue generation.

Can this country really become a different place when the-black-body-as-white-property is a founding tenet of American democracy?

The president’s speech was rife with the language of American exceptionalism and praise of the “great experiment.” That he used class Black church sermonic riffs as the rhetorical backing for his message felt both familiar and strangely off-kilter. In his speech we could see the rhetorical influence of years spent under the tutelage of Rev. Dr. Jeremiah Wright, with none of the moral force or clarity of Wright’s jeremiads.

For what the president called exceptional, Black people have long called peculiar. Riffing on the reference to slavery, “the peculiar institution,” Black women thinkers frequently referred to the peculiar paradox of a place that commemorates and celebrates its belief in freedom while actively withholding access to whole groups of people.

Though she did not use this language, this sentiment and rejection of America’s peculiar history can be found in Diane Nash’s strident refusal to march across the Pettus bridge with George W. Bush. A strident believer in nonviolence, she considers him a war-monger. Just as she was a radical dissenter, and one of the architects of both Freedom Summer and Selma ’65, we should pay attention to Nash’s dissent today.

A country wherein police departments routinely treat their most vulnerable citizens as sources of revenue creation is no democracy. (Hell, a country where profits matter more than people is no democracy.) A country where the “officers expect and demand compliance even when they lack legal authority” is no democracy. A country where officers are “inclined to interpret the exercise of free-speech rights as unlawful obedience, innocent movements as physical threats, [and] indications of mental or physical illness as belligerence,” is a veritable police state.

In her most political episode to date, Shonda Rhimes waded into the waters of unjust policing in last week’s episode of “Scandal.” After it is proven that an officer unjustly shot an unarmed Black teenager, in a chilling and telling monologue, the officer says:

People like me… everyone, including little babies are taught to look at us like the enemy. They are taught to question me. To disobey me. And STILL I risk my life for these people… all I hear about on the news are dirty cops. Cops who shoot innocent Black kids. It’s CRAP. There were 84 murders in this city last year. Were all of those cops shooting innocent Black boys? Hell no. Those were Blacks turning guns on each other. Yet I’m the animal. Brandon Parker is dead because he didn’t have respect. Because THOSE PEOPLE out there who are chanting out there who are crying over his body didn’t teach him the right values. They didn’t teach him respect… Questioning my authority was NOT his right. His blood is NOT on my hands.

As the Ferguson report argues, “The officers expect and demand compliance even when they lack legal authority.” The “Scandal” episode aired exactly one day after the Ferguson report was released and exactly one day before 19-year-old, unarmed Anthony Robinson was killed by police in Madison, Wisconsin.

I heard many young Ferguson activists upset that we needed a federal report to confirm their accounts of years of unjust interactions with police. Accounts from Black people about the racial injustice we experience or witness are generally not believed without requiring more than reasonable levels of proof. And the tendency among many would be to watch the “Scandal” episode, and either insist defensively that Shonda Rhimes and the episode writer Severiano Canales don’t know how officers think, or conversely that all officers don’t think this way. The officer depicted, they would tell us, is just one bad apple. The Ferguson Report suggests that this is not so, but is part of an attitude among police when they engage with citizens, particularly African-Americans. Many officers forget that they have authority primarily for the purpose of protecting us and our rights.

In that regard, this report does powerful work. The convergence of the report, the “Scandal” episode, and the killing of yet another unarmed teen during the same week as we commemorate the 50th anniversary of Bloody Sunday should remind us of how far we have not come. The work of democracy and the work of securing racial justice in a country built upon the pillars of white supremacy is never a finished project. Part of that work among Black people will be remembering that we are fighting for all Black people, not just for men and boys, whom Obama referenced in his speech, and whom “Scandal’s” fictional protesters referenced when they yelled, “Stand up. Fight back. No more Black men under attack.”

What we require is vigilance at every level. We require protests. We require federal investigations. We require community policing. We require principled dissenters. We require radicals who push from without and reformers who push from within. There is a place for everybody in the work we are called to do.

Old habits die hard, and this country is in love with its bad habits. But the systematic mistreatment of African-American people is a bad habit we should no longer accept.