The ridiculous email “scandal” involving Hillary Clinton is but the latest example of the media echo chamber. Journalists are too enamored with this “scoop” to let the story go, or even to admit that it’s less of a scandal than they were hoping for. The Republicans are palpably excited for the obvious reason that Hillary Clinton is the Democratic frontrunner and they’re still smarting from the slow fizzle of their trumped up Benghazi conspiracy. Since admitting error is impossible for them, they’re hoping to re-engage Benghazi by way of emailgate. Denying real problems—poverty, racism, climate change, gender inequality, gun violence––they constantly need to find new pseudo-events on the scale of birtherism to pretend that there is life beyond fear of change in the GOP agenda.

Hillary Clinton is not just any politician. She is a Clinton, and is treated as such, which is to say, an extension of her husband. As secretary of state in the first Obama term, she got a pass for as long as delegitimizing the president remained priority one. Before Benghazi fell into their laps, she was still being perceived by GOP busybodies as one who retreated from power (her heated quest for the presidency) to serve under the smooth-talking black man who stole the nomination from her.

Benghazi brought back the old Clinton baggage. As in the present politicized non-crisis, the past invention of a Benghazi backstory centered on communications. Hillary was/is regarded as too secretive, plotting something that Republican investigators take it upon themselves to expose. There must be a Clinton cabal—the death of Vince Foster and Whitewater investigation being prototypes here. One can easily detect the role gender plays in the mounting confusion, which the media frenzy only feeds. Smelling conspiracy is the neocons’ stock-in-trade.

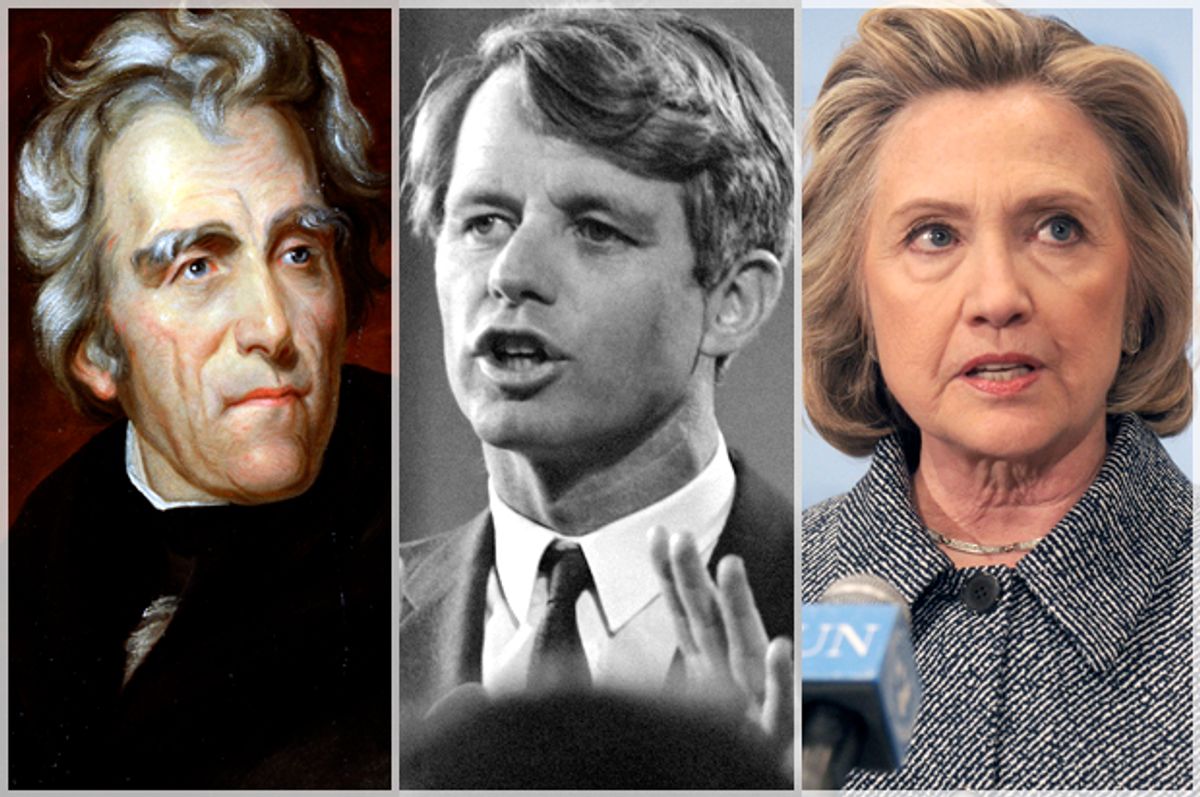

This is not new at all. There was an instructively comparable non-crisis in Washington shortly after Andrew Jackson became president. Margaret “Peggy” Eaton was the attractive daughter of a local boardinghouse owner, a working-class widow. Her recent marriage to the Tennessean John Henry Eaton, Jackson’s longtime subaltern, and new secretary of war, catapulted her to national visibility. A national political scandal arose when the other cabinet wives overtly snubbed her. Mrs. Eaton was accused of transgressing the rules of etiquette, of trying to force her way into the circle of elite women in Washington City. Rumors were spread of her moral deficiency—they said she caused her first husband’s suicide when he learned of her tryst with then-Senator Eaton. Rumor and ridicule outpaced the facts. Secretary Eaton’s career was ruined, because he could never overcome the “hit” his opposition had taken out on his wife. Impropriety was the alleged crime, and female ambition the real cause. Jackson, the Eatons’ protector, was so incensed that he fired his entire cabinet and started over again.

Jimmy Carter learned a Washington lesson when his rusticated, beer-guzzling brother Billy became the fodder for jokes; Bill Clinton learned when his half-brother Roger got in trouble for cocaine use, too. You can’t choose your family. But—and here’s the difference—you can choose your spouse. When marriage is mixed with politics, and reports of corruption are connected to that marriage, Americans are more likely than not to look unfavorably on that politician. And this is more true for women than for men.

Why this matters is because the media is always (at least subconsciously) looking for the flaw, or some misstep, that returns Hillary Clinton to the sordid script of her husband’s morally checkered presidency. Commentators glibly repeat the Republican presumption that the Clintons routinely break rules, take advantage of gray areas in the law, and are ruthlessly driven by their desire for power at any price. This is an old, tired trope. It began when Arkansas newspaperman Paul Greenberg anointed Bill Clinton “Slick Willie” way back in 1980; it was an almost predictable southern slur that painted Clinton as low-class con man, and that followed the Democrat to the White House. Though a Rhodes scholar and Yale Law School graduate, Bill Clinton was routinely mocked for his white trash ways: his greasy diet, smooth southern drawl, and, not inconsequentially, his mother’s dubious background: she was recalled as one who had been married four times, and could be seen with her “skunk striped hair” and “racing form in hand”; Virginia Clinton was from the wrong “pedigree,” as the Florida reporter Bill Maxwell wrote in 1984. Like Peggy Eaton.

Hillary Rodham Clinton’s background is dramatically different. She was a midwest Methodist, middle-class, who somehow sacrificed her moral rectitude when she married Bill. Their marriage has always been portrayed by critics as morally compromised, a self-serving political partnership, a union forged in shared ambition instead of as a union of hearts. Paul Waldman of The American Prospect captured this unpretty logic perfectly when he recently wrote of the email brouhaha that every Clinton scandal stemmed from a single source: the couple’s screwing up “with some questionable decision on your part, your husband’s, or both.”

In the opposition’s apparently effective narrative, Hillary is forever enshrouded in her questionable marriage. Her mistakes inevitably are (or else resemble) Bill’s mistakes, and vice versa. The most ridiculous comparisons are already being made between Hillary’s secret email server and Watergate, forgetting, of course, that President Nixon’s scandal involved violation of the Constitution, abuse of power, and misuse of the IRS, FBI, and CIA. But for her Republican detractors, the facts hardly matter. A more interesting comparison might be made to Nixon’s attorney general John Mitchell, who crashed and burned during Watergate–in part owing to his outspoken estranged wife Martha, who was born in Pine Bluff, Arkansas. During that real political crisis, she become a major liability for the embattled, hard-nosed attorney general. Thanks to the insatiable media, though, the loose-lipped, alcoholic political wife was a sideshow, widely portrayed as delusional when she made inconvenient statements and slung dirt—much of which turned out to be true.

The media are perversely enamored with the Hillary email server story, and are primed to exaggerate its significance. The “lemming-journalism” effect is really what causes a “scandal” like this to enlarge. “What Are the Clintons Hiding?” is a Republican mantra, always held in reserve, and ready to be dragged out in tired talking points whenever a flock of journalists will gather. The Clinton narrative revolves around the assumption that the husband and wife are a canny pair of political manipulators who, if unpoliced, will slither out of the grasping hands of duty-bound reporters. In this mode of thinking, Hillary must have used her email to conceal nefarious wrongdoing. The mere taint of impropriety is enough.

Why is there this particular Clinton narrative? And why must Hillary be seen as a carbon copy of Bill? For one, little of his skill as a campaigner has rubbed off on her. Yet she is presumed to have inherited from “Slick Willie” the Arkansan’s art of dissembling. The burden for Hillary is magnified, because Americans historically distrust ambitious women. Alexander Hamilton, nowadays the unlikely hip-hop star of the New York stage, once wrote about the dangers of seduction. In one of his essays in The Federalist Papers (No. 6), a piece most lawyers and political experts have ignored, he said that women who engaged in court politics corrupted high-minded political governance.

Are we still stuck in that ancient mindset? While Hamilton had France in mind, scandal-mongering American journalists have never truly freed themselves from this once-alluring trope. Former Senator Hillary Clinton served four years as a highly effective secretary of state. Yet she will always been viewed as Bill’s partner in crime, a morally compromised spouse. Guilt by association.

Obviously, journalists have drawn comparisons between the Clintons and Bushes. But Bill and Hillary are not a dynasty. They have no pedigree, no lineage, no inherited family reputation to reflect on. Ironically, Bill Clinton does not even have the surname of his actual father, who died in the months before he was born. There is something else unusual about the Clintons as a power couple. One of few ways early Americans approved of women holding office came through the acceptance of widows, replacing their dead husbands in their congressional seat. The first woman elected to the U.S. Senate was Hattie Wyatt Caraway of Arkansas, who was appointed to fill the vacancy caused by the death of her husband and was then elected on her own in 1932 and again in 1938. Rose Long replaced assassinated husband Huey Long in 1936; Vera Bushfield repeated the pattern in South Dakota in 1948. In fact, the twelve women appointed or elected to the Senate before Florida Republican Paula Hawkins in 1981 were typically widows, or appointed by their governor-husbands; only one of the twelve was unmarried. The old common-law tradition that women can serve as deputy husbands, temporary proxies for dead spouses, is the way many Americans still imagine a comfortable role for women in politics. The idea underlying the practice is that women are meant to be devoid of personal ambition. A woman should only aspire to power in an emergency.

The problem, of course, is that Bill Clinton is not dead, and neither is Slick Willie, his white trash moniker. We should take a serious look at why our nation has been distrustful of placing women in positions of power. To make the point clearer, we have the latest revelation about corporate power: more men with the name John head major corporations than all women. Hillary is disparaged for her strength and resilience, and for exhibiting presidential ambition; in this, she can only be viewed as an extension of her husband. All will recall that the only time Hillary was widely popular during her husband’s presidency was after she was humiliated by exposure of the Monica Lewinsky affair. Suddenly, more traditional women felt empathy for her. When she wallowed in embarrassment owing to a cheating spouse, she appeared less threatening (and more like a “regular woman”). In the persistent Clinton narrative invented and perpetuated by reporters, she was finally paying the price for her bad marriage.

It is time for journalists to abandon the Clinton marriage narrative and start covering the real issues: Who is Hillary Clinton when it comes to addressing foreign policy and military matters, trade and economic policy, civil rights and economic fairness? What sectors of the population would benefit from her policies? Think of all the twentieth century presidents who cheated on their wives: Woodrow Wilson, FDR, Dwight Eisenhower, JFK, LBJ, and (if the rumors are correct) George H. W. Bush. Does a male politician’s sexual disloyalty tell us anything of any significance about his political stands? Let’s reflect for a moment on all the kudos Barack Obama has received from “family-values” Republicans for his scandal-free happy marriage. So, isn’t it time to stop measuring Hillary Clinton by her marriage?

It seems clear enough that invasions of privacy in our interconnected world will continue to have a very palpable influence on politics. It will continue to move back and forth across partisan lines, too. As Mitt Romney learned when he uttered the words “47 percent” in friendly company, anonymous cell phone audio and video recordings are making it to the national news every day now, unleashing media frenzies that may or may not be deserved. The Internet is a site of considerable confusion and insecurity, and Hillary Clinton may well have chosen to work from her private email account for a host of reasons that are not conspiratorial.

But that’s not the entire point here. It’s the gendered script that is most tiresome. No one thought of John F. Kennedy as weak because he appointed his brother Bobby to his cabinet. This other senator from New York with presidential ambitions developed a political identity independent of his martyred brother. Whatever this tempest in a teapot over her use of email is, it is not a “Clintons” scandal. It is time to start talking about Hillary Clinton in the singular, and to let any missteps–whatever weight they deserve to be given–be her own.

Political scandals with national security (and communications) ramifications are cyclical. It is a different world from the time of Watergate and a president’s criminal use of the CIA and other agencies to wreak political havoc. That kind of activity produced the Church Committee, which thoroughly examined domestic spying and, for a time, brought a bit of transparency and Senate oversight of the national security agencies. The security state was shielded again after 9/11, a level of protection from public exposure brought down by the revelations of Edward Snowden.

Email is insecure. Important people care about that more than you or we do. Maybe Hillary figured (with good reason) that somehow her conversations about the sums she was spending on Chelsea’s wedding would be leaked. That’s the level to which “news reporting” has sunk. So now, because of Hillary’s at-home email server, a host of presidential wannabes are going to have their separation of private and public emails examined. Journalists will dig up what they can. Until that becomes old news, too.

It is certainly a different world from what it was in the 1990s, when Mrs. Clinton served as First Lady. Whether or not she succeeds in becoming the first female U.S. president, more of Hillary Rodham Clinton’s emails will be scrutinized; more of her will be in the public record than she would like—that’s just the way it is. This is the age of anonymously captured videos posted on Youtube that go viral; public personalities’ off-hand comments demand public retractions and public spin. The celebrity’s handlers step in. The Peggy Eaton Affair was nothing compared to this, and it resulted in the dismissal of the president’s cabinet.

No one runs for president anymore unencumbered by invasions of their private life and electronically generated, sensation-producing gossip and conspiratorial hints. And the media will, all the while, pretend that what drives the day’s reporting are their attempts to uncover where the candidates stand on the issues. Watching the 2016 campaign will take us all closer to being part of a video game, with the sweaty palms of the media at its controls.

Shares