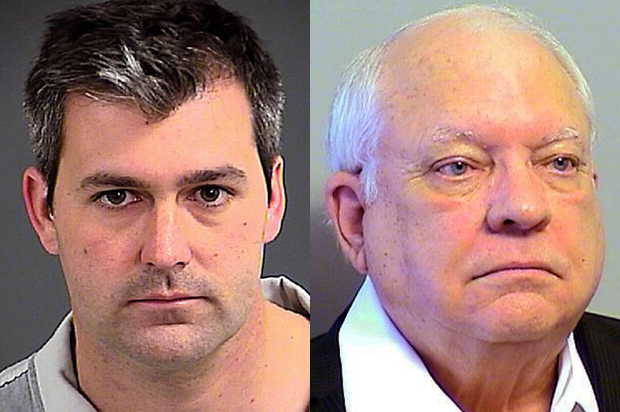

On April 2 in Tulsa, Oklahoma, a sheriff’s deputy named Robert Bates shot and killed Eric Harris, a man fleeing a crime scene where he was about to be captured for selling illegal weapons. Bates, a reserve deputy who is allowed to work on cases because he is a big donor to the sheriff’s office, was charged this week with second-degree manslaughter, after claiming that he meant to reach for a taser and not a gun.

As Harris lay struggling and dying, he told the surrounding officers, “I’m losing my breath.” One officer yelled back at him, “Fuck your breath!” Then he insisted that the dying man be handcuffed.

“Fuck your breath!” encapsulates in only three words the systemic disregard that police regularly show to Black people in America. Just last week, we watched Michael Slager execute Walter Scott in South Carolina for daring to run away. Now this week, we are also tuning into the trial of former Chicago Police Officer Dante Servin, who is charged with involuntary manslaughter in the killing of 22-year-old Rekia Boyd in March 2012. In the cases of Eric Garner in Staten Island, Tamir Rice in Cleveland, Walter Scott in South Carolina, and Eric Harris in Tulsa, we have seen video of law enforcement officers not only critically injuring citizens but also refusing to administer medical care, with fatal consequences.

Given the origins of policing in this country and their connections to slave patrols and other forms of racialized social control, I am under no illusions that the police have ever held Black life in high regard. Police complicity and participation in lynchings and in the KKK make that clear. But the explicit, tacit refusal of Black people’s right to breathe is still significant. The fact that the Tulsa County Sheriff’s Office is a pay-to-play force is significant. The fact that white men can sign up with government approval for the right to play cops and robbers on the weekends is appalling. That Black lives provide fodder for state-sanctioned sport should have us in the streets.

There is something about the logics of self-governance under the terms of neoliberalism that make this moment feel more pessimistic than our trite narrative of linear progress on racial issues would have us conclude. In 2012, the United Arab Emirates gave $1 million to the New York City Police Foundation. According to an NYPD spokesperson, the money was used to upgrade equipment and aid in criminal investigations. In both New York City and Tulsa, private funding of law enforcement significantly impacts the way local policing is done. In Tulsa, it results in the pay-to-play scheme. In New York City, it allows for large infusions of cash donations whose specific uses do not come under public scrutiny because they are private funds.

These forms of neoliberal policing — in which private citizens and private monies impact the culture of policing but escape governmental checks and balances — endanger us all.

In New York, such actions enable the purchase of unspecified forms of “equipment” that might, for instance, be used to exacerbate the culture of militarized policing in the NYPD. Part of this money allows the NYPD to travel to the UAE to learn counterterrorism measures. In the wake of 9/11, some external training might be helpful, but essentially, this sounds like a case of the NYPD being allowed money to play global cops and robbers, and to then test out these tactics on the Black and Brown people who are policed heavily within the city.

In the case of Tulsa, this privately underwritten form of law enforcement placed an underprepared “pretend” deputy into a serious confrontation. As a result, Eric Harris lost his life.

But he did not just lose his breath. As he lay dying, he was refused the right to breathe. That refusal came in a chorus of other taunts about how he was getting what he deserved because he chose to run. His breath seeped out of his Black body as public service officers taunted him in a barrage of profanity.

Why is the refusal of breath to Black people endemic to the American condition? What about the Black body makes the life-breath that we all hold so dear — so sacred — such a profane and devalued thing in the hands of white people?

In 1977, the famous writer and American prophet James Baldwin returned to America after living in France for more than three decades. In an interview at the New York Times, he said:

“I left America because I had to. It was a personal decision. I wanted to write, and it was the 1940’s, and it was no big picnic for blacks. I grew up on the streets of Harlem, and I remember President Roosevelt, the liberal, having a lot of trouble with an anti- lynching bill he wanted to get through the Congress–never mind the vote, never mind restaurants, never mind schools, never mind a fair employment policy. I had to leave; I needed to be in a place where I could breathe and not feel someone’s hand on my throat.”

Baldwin names a moment that sounds similar to our own. The vote is insecure from racial tampering. Indiana has just passed legislation that allows businesses (including eateries) to discriminate against customers based on “religious” assessments of their fitness to be served. Our public schools are in abysmal condition and throughout the country fast food workers are waging the Fight-for-Fifteen, a campaign for a $15 minimum wage.

Baldwin illuminates for us the way that America exists as a place predicated on the refusal of Black breath and the denial of Black people’s right to move freely in the world without losing our lives for having a broken taillight or playing with a toy gun, or for standing on the street chatting with friends.

This refusal of breath is not only anti-Black, but multigenerational, and harder to combat because of the way neoliberalism and acts of privatization have invaded police forces. As Eric Harris’ breath left him, other officers reminded him that “you ran!” Similar charges were levied against Walter Scott by pundits and commentators last week. “Why did he run?”

Neoliberal structures of self-governance demand that we all control ourselves and “do the right thing,” in order to avoid negative consequences. Meanwhile, the conditions that enable us to actually do the right thing continue to slip away. Walter Scott ran because as a poor Black man who was in arrears on his child support, he did not want to be subject to a long prison sentence and fines he could not pay. The sense of precariousness about not being able to enjoy simple pleasures, like going for a ride on the weekend because you might find yourself in prison interminably for bills you can’t pay, is surely not just.

These are not justifications for Walter Scott’s wrongdoing. They are reminders that many of us manage to do the right thing because we live in conditions that allow us to pay bills, adequately support our children, and find sufficient employment. Many, many Americans, a disproportionate number of them Americans of color, do not live in such conditions.

Yelling at them or executing them for making bad choices in a system that offers limited options shows us how often we miss the point. Under this kind of logic, the supposed lack of control of working-class Black and Brown people justifies the stultifying overpolicing of our communities, the stranglehold of our prison system saddling Black people with jail time, fines, probation, parole and a constant sense of threat, and finally, the ultimate refusal of one’s breath by a trigger-happy police officer if you fail to submit in any way to this unjust state of affairs.

Something must change. For we are all losing our collective breath. We all watch as the police and the state communicate their clear disregard for the value of Black life. The weight of historical injustice and present injustice constricts, makes us writhe in agony, makes us go out to protest.

That the officers in each of these three killings are being tried is nothing to celebrate. We do not celebrate our country for doing the right thing. Charging those who unjustly kill others with murder or manslaughter is basic.

Figuring out how to let Black people live is apparently far more complicated.