Whenever there's a new scandal about fabricated or otherwise dubious material in a celebrated nonfiction book, many people want to know how the author could have been so foolish. Don't writers realize how mercilessly scrutinized their work will be? Haven't they learned from the mistakes of so many of their peers?

They haven't, and they have. First, the likelihood of any given author producing a book popular enough to invite post-publication fact-checking is very, very slim. Second, while some authors have seen their careers crash and burn over such transgressions, others never suffer anything worse than a thorough scolding. Take James Frey, the most infamous example of a fibbing memoirist, a man whose dishonesty earned him a dressing down from no less than Oprah Winfrey herself. The uproar did nothing to slow the sales of Frey's two memoirs, and now he runs a thriving book packaging company with a sideline in movie and TV development.

Talk about mixed messages! We say we value memoirs and other nonfiction works precisely because they tell us what really happened. Then, when the amazing true story turns out to be a bit less than absolutely true, some of us fulminate about it for a while, even as countless more continue to pony up for the tale. We want the story to be amazing and we want it to be true, but an awful lot of us are willing to countenance some fudging on the true part if the author will tell us what we want to hear.

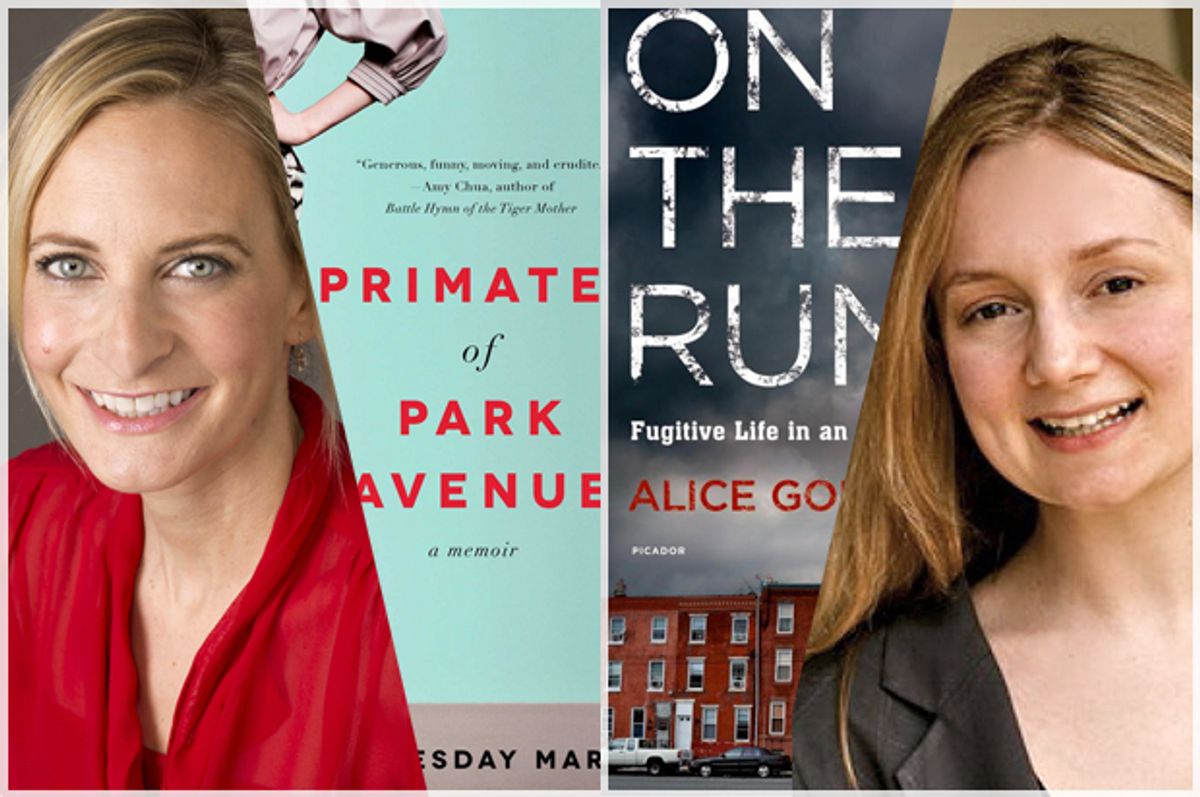

The two latest examples of this syndrome came under fire over the past few days: "Primates of Park Avenue" by Wednesday Martin and "On the Run: Fugitive Life in an American City" by Alice Goffman. Martin's book -- published just last week and heralded by a piece in the Sunday New York Times that introduced the paper's readers to the concept of the "wife bonus" -- purports to describe the odd and exotic customs of Manhattan's posh Upper East Side. It's a society where families headed up by rich, powerful men in the finance industry are administered by exquisitely manicured stay-at-home moms. (The wife bonus is allegedly paid to a spouse who has performed exceptionally well in that role.)

"On the Run," on the other hand, recounts what Goffman, an assistant professor of sociology at the University of Wisconsin, learned and experienced during six years she spent living in a low-income and predominantly black neighborhood in Pennsylvania. Goffman, whose book was greeted by warm reviews and a profile in the New York Times last fall, first came under attack when Steven Lubet, a law professor at Northwestern, observed in the New Rambler that if her account of a particular incident is indeed accurate, then Goffman might well have committed a felony.

In the passage in question, Goffman describes driving some of her friends/subjects around while they searched for the young man who had killed one of their friends. Their stated intention, unfulfilled, was to exact mortal revenge. (Lubet also questions the veracity of several other elements of "On the Run.") Goffman's response to Lubet's criticisms countered that, while at least one of her passengers was armed and while she admits that she herself "wanted Chuck’s killer to die," the drive did not constitute a serious attempt to murder the murderer and was merely a ritual of "mourning." Lubet regards this as a contradiction of the published version and maintains his skepticism about "On the Run."

While Goffman is a bona fide sociologist, Martin is something else, a self-described "cultural critic at large in high heels," who boasts of her Ph.D on her website but seems to have little practical training in field research. Nevertheless, while labeled "a memoir," "Primates of Park Avenue" is styled as an ethnographic excursion. Two reporters for the New York Post, Isabel Vincent and Melissa Klein, went to town on the book, catching Martin in numerous large and (mostly) small inaccuracies and conflations, such as an account of being interviewed by a co-op board in bed during the late stages of a difficult pregnancy. Martin does not appear to have been pregnant when she and her husband moved to the Upper East Side in 2004.

That both of these books should be challenged at the same time is striking. Both promise their (presumably middle-class) readers an inside look at milieus that fascinate, if for very different reasons and at opposite ends of the economic spectrum. What the poor black community Goffman studied shares with the rich white enclave that Martin infiltrated is a fabled role in American popular entertainment. Each of their books seems to have gone awry because of its willingness to tap into by our favorite narratives about the community it portrays.

The appeal of "Primates of Park Avenue" is blatant. Martin promises a voyeuristic window on a lifestyle that many people clearly envy, whatever they may protest to the contrary. Dishy tales of the strange behavior of rich people is an established genre, whether we're talking about historical novels set in the Tudor court or the posher precincts of the "Real Housewives" franchise. What we want from this genre is to vicariously revel in aristocratic luxury while being assured that the people who possess it are our moral inferiors. Maybe all that money turns them awful or maybe you just have to be awful to get it.

The "wife bonus" tidily meets this need. Whether or not Upper East Side husbands really make a habit of dispensing such bonuses (Martin has backpedaled a bit on that point), the concept is one designed to launch a thousand scandalized Facebook posts. It confirms the popular and titillating suspicion that marriage among the 1 percent is a form of domestic concubinage, and that the women who engage in it, for all their superficial perfection, are mainly in it for the money. At the same time, there's something obscurely gratifying about the handsome renumeration these wives get for providing services most other women perform for free and more often than not for very little respect or appreciation. The Upper East Side wife bonus allows us to congratulate ourselves for not commodifying the caretaking we do out of love, while assuring us that if we did, we'd be worth a bundle.

This is a form of entertainment obviously geared toward women, a middle-aged variation on the Manhattan-set teen soap "Gossip Girl." "On the Run," on the other hand, is more butch, a tale of crime and (sometimes) violence, of desperate lives on the edge; the press has incessantly compared it to "The Wire." Like Piper in "Orange Is the New Black," its white, middle-class, educated, blond author leaves her comfortable but staid routine and is plunged into a world of fear and suffering, but also of great excitement.

In an incisive review for Slate, published when "On the Run" first appeared, Dwayne Betts, a black poet who grew up in a neighborhood similar to the one where Goffman was embedded, acknowledged the strengths of her book. Goffman, he wrote, succeeds at conveying the pervasive surveillance and the perpetual threat of incarceration (or worse) that distorts the lives of young black men. But he goes on to complain of her "unrelenting focus on criminality." The appeal of the book, he insists, "comes from the danger she faced and the violence she witnessed. She gives what many readers expect: crack addiction and senseless crimes, including murder."

And why not? Driving a guy with a Glock in his waistband around all night certainly makes for better copy than hanging out with a single mother as she tries to stretch a welfare check to cover three decent meals per day. "Most young black men," Betts writes, "are not committing armed robberies and burglaries, are not engaging in armed battle from moving cars, and are not murdering acquaintances at dice games. They are not shooting into homes." But, let's face it, whatever they are doing is far less likely to result in a successful book that will impress the media with its author's tough and fearless derring do.

Some authors are ruined -- or come close to it -- when their work is revealed to contain fabrications or distortions; disgraced journalist Jonah Lehrer is a good example. But when that happens, it's often still an instance of the better story winning out over the weaker one. (In Lehrer's case, the saga of a slick, phony prodigy meeting his well-earned comeuppance has proven hard to beat.) Whether the criticisms leveled at Goffman and Martin will stick is hard to say, but the bald and boring truth is seldom a match for what we want to believe.

Shares