Lucia McBath says she has forgiven the man who shot and killed her son, Jordan Davis, at a Florida gas station on the day after Thanksgiving in 2012. She says it is an important aspect of her faith as a Christian and her ability, as a human being, to endure what happened and keep going. Jordan’s father, Ron Davis, does not feel quite the same way, and I can’t imagine that I would either. Like any other parent, I hope and pray that I will never have to find out, but beyond that there are aspects of McBath and Davis’ experience that I will never know about firsthand.

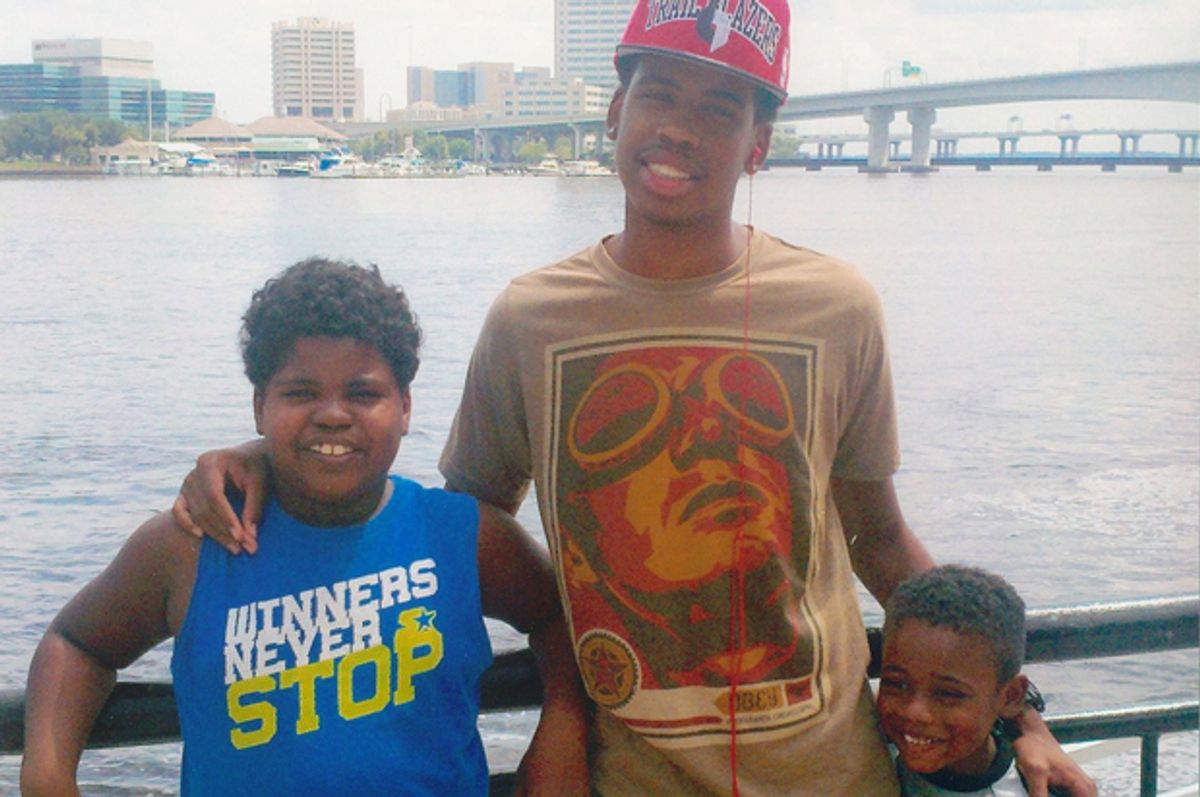

Their son Jordan was a young black male, a 17-year-old kid who was out being rambunctious with three of his friends, who were also black. They were looking to meet girls and had stopped at the gas station to buy gum, so their breath would be fresh. They were playing hip-hop music loud in their Dodge Durango and got into a verbal altercation with Michael Dunn, a middle-aged white man who had consumed several rum-and-Cokes that day at a family wedding. (To be specific, it was the wedding of an adult son Dunn had not seen for years, a detail that ought to be irrelevant but isn’t.) Dunn had a loaded handgun in his glove compartment, and as the confrontation escalated he took it out and fired into the Durango 10 times. It’s almost miraculous that Jordan Davis was the only person hit.

The killing of Jordan Davis came to be called the “loud music shooting” in the media, but that was one of those all too frequent cases in America where we use coded phrases to obfuscate the obvious. What happened that night had nothing to do with music, except as a kind of cultural signifier. That Black Friday episode in Jacksonville distilled America’s race problem and America’s gun problem into three-and-a-half minutes, as becomes increasingly clear in Marc Silver’s riveting documentary “3 ½ Minutes, Ten Bullets,” made with the cooperation of McBath and Ron Davis, extensive courtroom video footage and access to Michael Dunn’s recorded phone calls from prison. In the wake of this week’s shocking massacre at an African-American church in Charleston, South Carolina, even the most obtuse people in our country can't avoid noticing that America’s disordered racial history and our fetish for guns are interwoven into a single sinister narrative.

Whether or not Dunn really felt threatened by Jordan and his friends, as he told the police and later testified, he was clearly incapable of perceiving them as individuals. He saw four young black males in an SUV, listening to rap music, as “gangsta rappers,” members of a dangerous “subculture” who wore baggy pants, came from fatherless households, sold and used drugs and represented a world of lawless violence. Although this makes no difference in legal or moral terms, since at worst the four teenagers were guilty of exuberant behavior, those stereotypes were wildly off base in this case. Jordan Davis and his friends were middle-class kids from the suburbs, looking to have fun on a Friday night. They weren’t gang members or criminals, they weren’t drunk or high and despite the wild theories floated by Dunn and his lawyers later, they weren’t armed.

Michael Dunn would actually be a comic or pathetic figure if he hadn’t taken a human life for no reason, and destroyed his own life in the process. (“I’m not racist,” he tells his fiancée in the movie. “They’re racist.”) As I wrote while discussing the widespread phenomenon of white historical denial last weekend, there was a good deal of psychological projection within Dunn’s racial animus: He was the one who was intoxicated; he was the one who had lost contact with his own child. (Jordan Davis had a close and loving relationship with both his parents, although they no longer live together.) He was the one who introduced lawlessness and deadly violence into a situation that would have been easy to deescalate or back away from.

While the story of Jordan Davis and Michael Dunn is a dreadful human tragedy, as well as an entirely avoidable one, at least a travesty of justice was not piled on top of it. In Silver’s film, Ron Davis remembers getting a text from the father of Trayvon Martin a few days after the shooting, welcoming him to a club that no one wants to join. In a state already traumatized by the Martin case, Michael Dunn’s murder trial came to be seen as a test of Florida’s criminal justice system, and also of the state’s notorious “stand your ground” law, which does not require people who feel endangered by others to retreat. After two trials, a jury of Dunn’s peers evidently concluded that the only threat he experienced was in his own head.

Whether or not you followed the Davis-Dunn case closely, it’s more than worth it to experience the remarkable twists and turns of the story as told in “3 ½ Minutes, Ten Bullets.” I met with Ron Davis and Lucia McBath in New York recently to talk about how the movie and the shifting public consciousness around the Black Lives Matter campaign have helped them keep going since their son’s death. I began by saying to them that every parent, of every race and every background, fears what happened to them: Our children are not supposed to die before we do. I didn’t need to ask whether they would have willingly given their own lives for Jordan’s because I already knew the answer.

“I feel that we have given our lives,” McBath said quietly. “We can’t have Jordan back, but we want to devote our lives to this issue – to talking about the problems of racial injustice and gun violence in this country, so that this does not have to happen to other people’s children.”

It can’t be easy to go around the country talking to strangers about your son’s death, and going through those emotions again. Has it also been helpful for you, on a personal level, to make this film and speak out in public?

Ron Davis: It’s a healing process, the more that you talk about it, the more that you change minds and hearts about the situation. When people see you as a human being and see Jordan as a human being, not just as an Other or a member of a group they don’t understand, I think this thing in your heart opens up. There’s another person who sees Jordan as a human being, and you know, 10 people, 20 people, a hundred people, a thousand people… On his website, we have 211,000 people who follow Jordan daily. So they see your son as a human being and I think that helps heal.

Lucia McBath: And then also, not just seeing Jordan as a human being, but getting people to think, “Yeah, young black men, they are human beings. And they do have value. Where have I fallen in the grand scheme of these kinds of attitudes about race and guns and violence? What do I really think?” When people hear about these heinous cases, they may read about it and look at it and go, “Ooh, that’s so terrible.” But everybody wants to shy away from it. It’s too scary to think about it, because you don’t want to be next. And you think, if you don’t think about it, or talk about it -- if you don’t do anything about it, you won’t be next. But that’s a fallacy.

What we hope through the film is that we can get people to take those blinders off, get them to open their eyes and look at the reality of gun violence and racial disparity, and the way people think about people of color, and get them to understand that everyone here, we’re all morally responsible for one another. We’re all morally responsible in a way that we treat each other, that we protect each other and care for each other. If we can do that with this film, if we can get people talking about those things, then we’ve done what we needed to do. We may never change their minds -- of course, ultimately, that’s what we really want to achieve, but if we don’t ever get you to that point, but we get you to sit here, at the table, and have these discussions with your family, and your friends, and your community -- beginning the discussion, then that begins to build the movement, towards finding racial justice, towards finding justice in the law. And that’s ultimately what I think everybody wants.

R.D.: See, you can touch more people than I can. We all have our groups of people that are our friends and our relatives. I can’t get in those circles. When you have your circle of friends, they may be able to say something to you, because there are no black people or people of color present that they don’t feel comfortable talking about that subject with. But around you and other people that are not of color, they will feel comfortable talking about it. And so you can ask them, well, did you see “3 ½ Minutes, Ten Bullets”? Let’s see what you think. Let’s see if we can talk about this. And that’s what we’re trying to do with the film, to get people to start having that conversation that we could never have, because we don’t have access. People don’t feel comfortable in mixed company talking about this.

You mean white people, I take it. Yeah, it’s difficult. What happened to Jordan was obviously an extreme example, but what struck me as a white person watching this movie was that the attitudes expressed by Michael Dunn are not that extreme or that uncommon. He didn’t use the N-word, he denied being a racist and he even steered away from saying the word “thug.” But he expressed this attitude that all black people essentially belong to the same category, and especially black males. They’re, like, interchangeable and identical and dangerous. I think any white person who is being honest will tell you they have heard co-workers or acquaintances or family members say things like that. And it’s easy to sort of let that go: “Oh, that’s just crazy Uncle Jack talking.” I think that’s extremely common. And to have it come up in this context really does confront you: What have I done about those attitudes? Have I tolerated that?

R.D.: And the extreme of that premise, we think, is at the end of the film where [Dunn] says, “Well, if it wasn’t me killing Jordan, somebody else would have had to, because he’d probably have killed somebody else anyway.” Why would you think that my child would have killed somebody, had it not been for him? In his mind, he’s doing this public service, you know? He doesn’t take any blame for what happened, it’s all on Jordan, 100 percent. We’re thinking we want to find other minds that are on the borderline of that thinking, and we want to pull them over to our side.

The guy at the gas station that pulled up before you, Michael Dunn, he stood his ground by saying, “I do not want to park next to these kids.” So he moved his car and parked over there, and he goes home to his family. You don’t go home to your family, because of the decisions you made. You spend the rest of your life in prison. To me, that is so vivid. That is the clash between him standing the ground, and this other guy standing his ground. If you stand your ground and you can retreat safely, you should. You shouldn’t confront a situation, and get yourself all worked up to the point where you want to kill somebody because they’re not looking up to you as an adult.

I wouldn’t ask or expect the two of you to feel any compassion or sympathy toward Michael Dunn, God knows. What he did was inexcusable, and he destroyed two families and two people’s lives. Maybe this is because I’m white, but I have to admit that I felt sorry for him on some level. I felt sorrow that a human being could be so consumed by hatred and fear as to do that. Because his life was wasted too, and whatever positive things he may have done have been wiped away.

L.McB.: Yeah. I have said this many, many times, and people look at me like I’m stupid when I say it, but I feel very sorry for Michael Dunn. I feel very sorry that he lives that existence, and that anger, and that hate, and that fear, every single day of his life. I mean, that’s enough to eat a person alive. I have gone even further to say that I have forgiven him -- but please understand, my thinking is, that frees me up. [Ron Davis shakes his head vigorously.]

That frees my soul. He will deal with God. He righteously will stand before God, and be dealt with. And I have nothing to do with that. But I have to free myself, so that I am not consumed by the very anger and rage that that man exhibits. And I think that ultimately you cannot be fully used by God to do the work, unless you set yourself free. It comes for everybody at a different time. Maybe Ron never will, and that’s OK too.

R.D.: I don’t believe that -- and Lucy of course is entitled to her beliefs – I believe that it’s not up to me to forgive him. I don’t have that in my brain, where he’s in there enough for me even to try and forgive him. I don’t think of him at all in that way. I think it’s up to him and God, he has to talk to God and be remorseful for his deeds before God. He’s not going to get on his knees and say, “I pray that Ron forgives me.” Now, maybe he’s going to get on his knees and ask God to forgive him. But I’m nothing to Michael Dunn. He doesn’t see me. So why should I put that on myself that I need to forgive him? He doesn’t see me. I’m nobody to him.

L.McB.: I have forgiven him because I had spent my entire life trying to teach Jordan about love, acceptance and forgiveness. So for me, not to do the very thing I was trying to teach my son is spiritual hypocrisy. And so, as much as I have not wanted to forgive him, I’ve had to. And also then there’s the difference between the male and female psyche. I’m completely serious. His son is murdered by another man! No, he’s probably -- probably no man is going to stand there and say, “I forgive you.”

R.D.: He has to mean something to you to forgive him! What you taught Jordan about forgiveness, it’s usually a family member that you get mad with, and you forgive them. Because they mean something to you. You understand? Or if you see a person on the street, a former friend, and you say, “Well, I forgive him. I know he did me wrong, but I forgive him.” Because that person meant something to you. What I’m saying is, Michael Dunn is not in my life. He never meant anything to me.

L.McB.: But, see, Michael Dunn doesn’t mean anything to me, either. But, I think, like I’ve said before, that this is the freeing of my soul or my spirit, so I don’t carry that with me for the rest of my life. He means nothing to me. And I really am very sorry that he’s living that sad existence that he lives in prison. But yes, he deserves it. He absolutely deserves it. And I wouldn’t have wanted to have it any other way, than to have him in prison.

Lucy, I was very moved by your moment of empathy with Michael Dunn’s fiancée in the film. I mean, she was somewhat implicated in what happened, or at least in the aftermath, although she didn’t kill anyone. But when you acknowledge that it took some courage for her to tell the truth about what happened – about what he said and did that night – that showed a largeness of spirit on your part, an awareness that another person was struggling to do the right thing.

L.McB.: Yes, all right, but understand me too that a lot of that was her protecting herself. I think in the long run, a lot of that was probably her rationalizing that she was going to go right down the same road as him if she didn’t do the right thing. I always go back to the very point that she says to him after he murders Jordan, “I want to go home.” They go back to the hotel. And she says, once they know that Jordan has been murdered, “I want to go home.” She doesn’t say, “Let’s call the police. Let’s make sure that we iron this out. If you shot him in self-defense, OK, then let’s go to the police.” She doesn’t say that. She says, “I want to go home.” And they lock the car in the garage and pretend like it never happened.

R.D: And I think, if the guy [at the gas station] hadn’t got their license plate, they never would have said anything to anybody. They probably would have found them because they had footage of her inside the store. If they could have identified who she was, they might have tracked them down. It would have taken a while, and he might have gotten rid of the weapon by then.

L.McB.: Had we not been able to find out who he was, had that man at the station not turned that information in, Jordan would have been just another black kid, killed by a white man who gets away with it. And that scenario happens far too often in the country.

I know you both felt it was crucial to pursue a murder conviction for Jordan’s death, even though as a practical matter Michael Dunn was already going to spend the rest of his life in prison after the first trial, in which he was convicted on three counts of attempted murder and got 60 years. Talk about why that final conviction was important.

R.D.: One part of that was that Angela Corey [state attorney for the Jacksonville region]and the district attorney were fresh off losing the Trayvon Martin-George Zimmerman case. She had to win this one. A lot of district attorneys wouldn’t have gone went back for a second trial when they had 60 years already. Michael Dunn was 47 years old, that was already equivalent to life imprisonment. They wouldn’t have spent the taxpayers’ money to go to a second trial. But they knew that me and Lucy were determined for justice for Jordan, and they knew we had platforms, and how much we would have talked in the news. So they had to go back.

L.McB.: And we knew that if we could win this case for Jordan and the other three boys then that would give some little justice for Trayvon, some little justice for all those cases where young men had been gunned down and people had walked away. Our son represented getting some kind of justice on a larger scale, setting a precedent for cases that came after ours. For us, it was kind of like a life or death situation.

R.D.: We felt the enormity of all these cases on our shoulders.

Were you aware of that significance from the beginning? Even amid your loss, were you aware that Jordan’s death symbolized a larger problem?

L.McB.: Yeah, I think we were. Because we had watched what had happened to Trayvon. And we knew that he had been demonized, and that no one got a chance to know who Trayvon was, and that was a huge problem with their trial. They weren’t allowed to even speak for themselves. They weren’t allowed to express who Trayvon was. They weren’t allowed to talk about the fact that Trayvon wasn’t doing anything wrong, other than just visiting his father, and being in a community where some people had the reaction that he didn’t belong. So we knew that this had to be looked at differently, that we had to go about trying our case differently, and that if we did not, we’re going to come up with the same results.

You didn’t want that media-circus atmosphere.

L.McB.: We did not, we did not. The first thing I asked our attorney, John Phillips -- I didn’t know a thing about him, but at Jordan’s funeral, I went to him, and I said very candidly, “You have to promise me, on your honor, as a man, as a lawyer, as a son, you have to promise me that you will protect my child in this situation. I’m charging you to protect him.”

So much has happened since Jordan’s death, in terms of the other high-profile cases: Mike Brown in Ferguson, Eric Garner in Staten Island, Freddie Gray in Baltimore and many others. And we’ve seen the emergence of the BlackLivesMatter movement, which I think has energized many younger people, and not just black people. Is consciousness changing? Do you see reasons for hope?

R.D.: They called me up for that, you know, to come lead the march for BlackLivesMatter here in New York in December. I was one of the people up front holding the banner that said “Black Lives Matter.” We had almost 15,000 people marching when we closed down Broadway. And I tell people that over 60 percent of the people saying, “Black lives matter,” were white, and they had their teenage sons and daughters with them saying, “Black lives matter.” And so that was significant. I was so proud of New York. They weren’t saying that white lives don’t matter, we know that, it’s a given. They were just saying, “Guess what?” to the white supremacists. Black lives matter, too. That’s who they were talking to.

L.McB.: I think overall, most people think that way. I think it’s a much smaller margin of people in this country that don’t feel that way. But I think it’s a problem that people who do believe that black lives matter don’t often interact with those circles of people who think in a different way. They’re afraid to talk about it, to tell their peers, “Well, no, black lives do matter.” But I venture to say that most people in this country know unequivocally that what’s happening in this country is wrong. They know that. And I think that a lot of them, too, are at a standstill. “Well, what can I do about it? I don’t know what to do about it. I’m just me.” Or, “I know it’s wrong, but I can’t get involved. I don’t have time.” Well, you need to make it your business, because the gun violence has gotten to epidemic proportions, and with the NRA going as strong as they are, this is going to get bigger and bigger and bigger. When the NRA is spewing hatred and fear, and driving people to go out and by guns in massive numbers, who are they buying them for? They’re buying them to protect themselves against those people that the NRA says that they should be afraid of.

How do you avoid feeling anger and bitterness toward a society that, first of all, seems to have this long-standing pattern, and second of all, seems so unwilling to confront it? To me, that’s almost worse than the history, which we cannot change – the fact that so many people are not willing to look at it clearly.

L.McB.: Well the thing is, are there any other alternatives? This is the best we got. So the only thing you can try and do is fix the broken system. We may never see it fixed in our lifetimes, and that’s not the issue for us. But if this is all that we have, and this is the best that we have -- and if you compare this model to other models in other countries, in third-world countries, it really is a pretty good model. It’s just fractured. People have become disenfranchised, and it’s just broken. So the best we can do is we can try and fix it in the limited time that we’re here.

”3 ½ Minutes, Ten Bullets” opens this week at the Village East Cinema in New York. It opens June 26 at the Landmark in Los Angeles and the Regal University Town Center in Irvine, Calif.; July 3 in Atlanta, Denver and Washington; July 10 in Miami and Vancouver, Wash,; and July 24 in Boston, New Orleans, Portland, Ore., San Diego, San Francisco, Santa Fe, N.M., and Seattle, with more cities, HBO broadcast and home video to follow.

Shares