I stumbled across mindfulness, the meditation practice now favored by titans of tech, sensitive C-suiters, new media gurus and celebrities, without even really knowing it.

I stumbled across mindfulness, the meditation practice now favored by titans of tech, sensitive C-suiters, new media gurus and celebrities, without even really knowing it.

A couple of years ago, I was deeply mired in an insane schedule that involved almost everything (compulsive list-making at 4am, vacations mostly spent working, lots of being “on”) except for one desperately missed item (sleep; pretty much just sleep). A friend suggested I download Headspace, a meditation app he swore would calm the thoughts buzzing incessantly in my head, relax my anxious energy and help me be more present. I took his advice, noting the app’s first 10 trial sessions — to be done at the same time over 10 consecutive days — were free. When I found the time to do it, it was, at best, incredibly relaxing; at worst, it barely made a dent in my frazzled synapses. When I didn’t find the time (because again, schedule), the effort to somehow make time became its own source of stress. In the end, I got an equally hectic yet far more satisfying career, took up running and forgot Headspace existed.

That is, until the term “mindfulness” reached a tipping point of near ubiquity. As it turned out, what I’d regarded as just a digitized form of guided meditation was actually a “mindfulness technique,” part of a bigger, buzzy, Buddhism-derived movement toward some version of corporate enlightenment. As long ago as 2012, Forbes reported that Google, Apple, Deutsche Bank and several other corporate behemoths already had mindfulness programs in place for employees. Phil Jackson, the basketball coach with a record-setting 11 NBA titles, tacitly praised mindfulness for his wins, telling Oprah he’d incorporated the technique into player practice regiments. Arianna Huffington, empress of media, not only sings the praises of mindfulness in speeches around the country, but she and Morning Joe co-host Mika Brzezinski just hosted an entire conference dedicated to it this past April. And perhaps least surprising of all, Gwyneth Paltrow is a proselytizing adherent, giving mindfulness in general, and Headspace in particular, a shout-out on her lifestyles-of-the-rich-and-beautiful website, Goop.

You can tell a lot about trendy new concepts by who embraces them, and why. In the case of mindfulness, business leaders cite a number of reasons why they’ve adopted the concept so wholeheartedly. Studies have found that mindfulness meditation reduces stress, thereby making it a safeguard against employee burnout. Research finds that mindfulness bolsters memory retention and reading comprehension, which means employees can be more accurate in processing information. One Dutch study found that mindfulness makes practitioners more creative, helping ensure workers remain a fount of ideas. And some schools for children as young as first grade have begun teaching mindfulness meditation, based on studies that suggest it helps maintainfocus, a resource in constant threat of short supply for those multitasking their way through so many mundane, workaday obligations.

The idea is that mindfulness helps cleanse cerebral clutter and hush neural distractions so we can redirect that brain power into being our most in-the-moment selves.

But really, we already knew this. Long before mindfulness became the path toward corporate good vibes — back when Westerners were getting into what was then simply called Zen meditation — millions were already offering unsolicited testaments to the restorative powers of the technique. (To modify an old joke about vegans, Q: How do you know someone’s into meditation? A: Oh, don’t worry, they’ll tellyou.) The pesky problem with meditation, now dubbed “mindfulness,” was its connection with Buddhism. Jon Kabat-Zinn, widely credited with introducing the concept of mindfulness to America in the 1970s, reportedly recognized the spread of the concept might be helped by loosening its religious ties. As a New York Times article on the practice explains, Kabat-Zinn redefined the technique, giving it a secular makeover and describing it as “[t]he awareness that arises through paying attention on purpose in the present moment, and non-judgmentally.” Without all that dogma attached, the opportunities for use were suddenly endless.

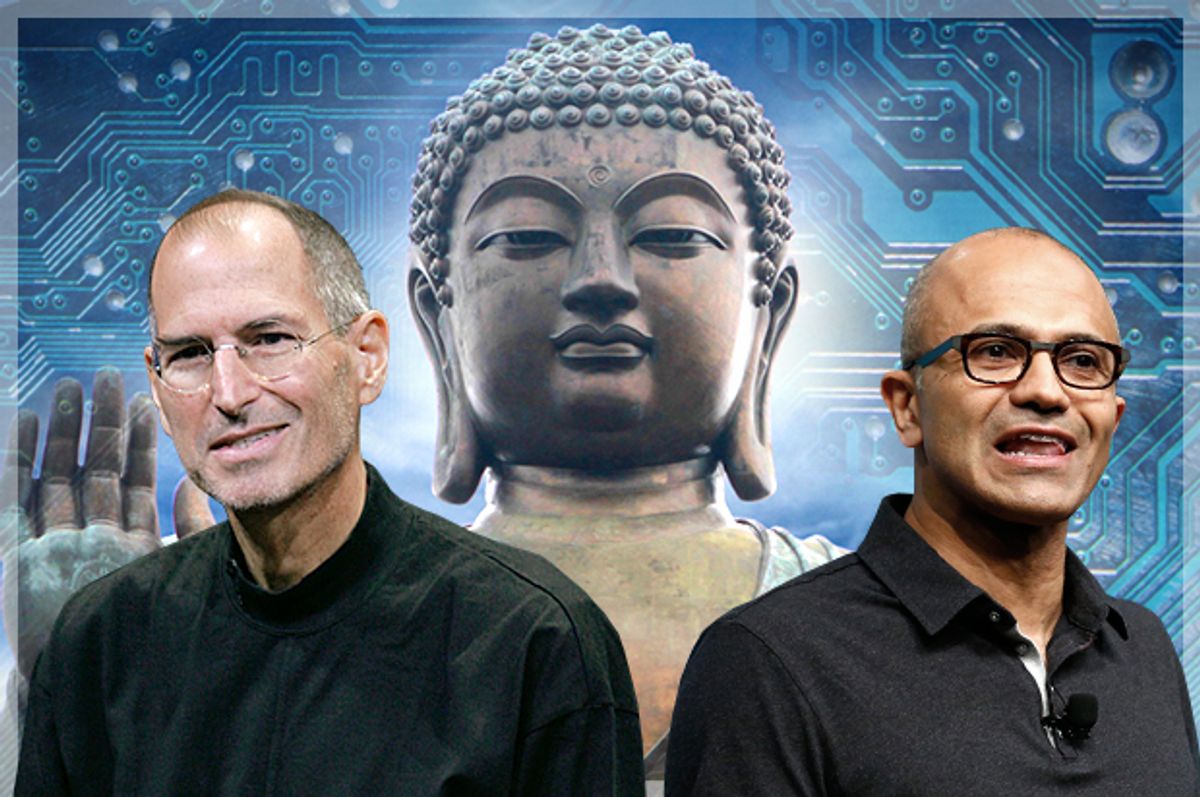

And there’s nothing business loves better than a good opportunity. Silicon Valley, which sits in the shadow of San Francisco and its countercultural influence, was first to recognize the benefits of mindfulness. In a New Yorkerpiece that explores the history of the phenomenon, Lizzie Widdicombe cites Steve Jobs — who traveled India as a teen and was an avid practitioner of meditation — as the first tech industry icon to weave mindfulness with business practices. His heir apparent in this arena is Chade-Meng Tan, whose title at Google is, no kidding, Jolly Good Fellow, or alternately, the slightly more formal Head of Personal Growth. Originally hired in 1999 as an engineer, in 2007 Tan headed up the company’s first "Search Inside Yourself” course, a two-day mindfulness-focused program. Since then, the corporate adopters of mindfulness, which also include Procter & Gamble, General Mills and Aetna, have grown to include companies in every area of business, stretching far beyond tech to banking, law, advertising, and even the United States military. (Although, it should be noted, deep meditation may actually be damaging for some PTSD sufferers, exacerbating the condition.)

Strip away all the fuzzy wuzzy, and one glaring fact stands out about mindfulness’s proliferation across the corporate world: At the end of the day, the name of the game is increased productivity. In other words, the practice has become a capitalist tool for squeezing even more work out of an already overworked workforce. Buddhism’s anti-materialist ethos seems in direct odds with this application of one of its key practices, even if it has been divorced from its Zen roots. In an article about “McMindfulness,” the pejorative term indicting the commodified, secularized, corporatized version of the meditative practice, David Loy states “[m]indfulness training has wide appeal because it has become a trendy method for subduing employee unrest, promoting a tacit acceptance of the status quo, and as an instrumental tool for keeping attention focused on institutional goals.”

A 2013 piece from the Economist titled “The Mindfulness Business” compares mindfulness to the culture of self-help, previously held as the cure-all for a business culture looking to maximize worker usefulness. The piece points out that this recontextualized version of meditation seems, cynically, to miss the point of the practice’s original intent:

“Gurus talk about 'the competitive advantage of meditation.' Pupils come to see it as a way to get ahead in life. And the point of the whole exercise is lost. What has parading around in pricey Lululemon outfits got to do with the Buddhist ethic of non-attachment to material goods? And what has staring at a computer-generated dot got to do with the ancient art of meditation? Western capitalism seems to be doing rather more to change eastern religion than eastern religion is doing to change Western capitalism.”

It’s a valid point that drives home the schism between the roots of the practice and the warped interpretation of it.

For now, there seems no end to the spread of mindfulness — which isn’t such a bad idea. The notion of self-care in an era of constant digital distractions, as well as midnight and weekend work email exchanges, is a welcome one. But what of the halfhearted appropriation of a noble, anti-capitalist practice to thicken the bottom line? As Loy notes in his Huffington Post piece, American Buddhist monk Bhikkhu Bodhi warns that "absent a sharp social critique, Buddhist practices could easily be used to justify and stabilize the status quo, becoming a reinforcement of consumer capitalism." That’s a pretty good summation of what’s already happening. Until corporate America discovers its next trendy panacea, the practice will continue to spread, its miraculous effects touted — and often overstated— as a booster of profits and more. It’s a bit like oms for making better worker drones; or rather, Zen done the American way.

Shares