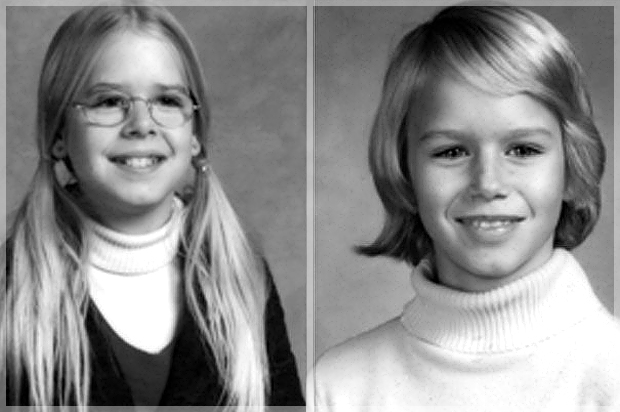

On March 25, 1975, Sheila and Katherine Lyon, ages 12 and 10, disappeared after spending the afternoon at Wheaton Plaza, a shopping mall in suburban Washington, D.C. Last month, authorities finally indicted a man for their murder, and authorities believe the girls were sexually assaulted before being killed. Lloyd Welch, a convicted sex offender, was linked to the scene by a sketch made from information given immediately after their disappearance to the police by Darlene (not her real name), a local girl, 13 at the time, a friend of the Lyon girls who saw them at the plaza the day they vanished and came forward with details about a man who had followed and leered at the sisters that day. Police made the sketch, dated two days after the girls were kidnapped, from the detailed description Darlene provided.

The sketch is so accurate it’s like a photo, right down to the scar on the man’s left cheek — it looks just like Lloyd Welch did at 18, down to its similarity to his 1977 mug shot from a later arrest. But the sketch Darlene helped police construct in 1975, the sketch that could have led to the apprehension of Lloyd Welch in 1975, was apparently not disseminated widely. It does not even appear to have been circulated well within the police department when the Lyon girls went missing.

Instead, based on a sketch made with details provided by another friend, a 13-year-old boy, police pursued a mystery suspect — the so-called “Tape Recorder Man” — who was never found.

Welch, meanwhile, was later convicted of sexually assaulting two 10-year-old girls, in two separate incidents, and is in prison in Delaware. That’s where detectives caught up with him in 2013 when a police investigator new to the case, Detective Dave Davis, reviewed a police interview with Welch from April 1, 1975, when Welch came in offering what turned out to be false information on the Lyon case. Davis immediately realized Welch needed further investigation. Detectives looked into him, found his 1977 mug shot and connected it to the long-dismissed sketch, which placed Welch at the scene of the Lyon girls’ kidnapping. Welch confirmed for police that he was the man in the sketch drawn from Darlene’s description.

Prior to that, Welch hadn’t even been a suspect.

***

I knew Sheila and Kate very slightly. I was 6 at the time they disappeared, and our families attended the same church. My grandparents lived on a street off of their street, and were friendly with their parents. I would later deliver the Wheaton News to their home. Their dad was a local radio personality, which made them stand out.

The girls went missing when I was in first grade, in the midst of my years of being sexually abused. They disappeared four months after my parents separated, at a time when my mother and aunt were active in the women’s liberation movement which was then in full pitch, calling on all of us to listen to women, to make a better world for girls and to pass the ERA. Sheila and Kate vanished just before Easter, and in the days around the pastel vibrancy of that holiday, within the blooming cherry blossoms and the soft magic that comes in early April after the cold of winter, officials searched for the girls, igniting terror in all of our hearts.

In a wrenching interview with the Washington Star 12 days after the girls were abducted, their mother Mary Lyon speculated that things would be different when the girls came home: “When they come home, Kate can get her ears pierced. And Sheila can wear eye shadow.”

But of course Sheila and Kate never made it home.

Attention to the case dwindled after the first year. Stories came out at the 5-year anniversary, then at 5-year intervals. One day in the mail, between a card from my aunt and the electric bill, I found a mass mailer with Sheila and Kate Lyon’s faces on it, age-progressed to look as they might in their mid-30s. There they were, staring up at me from the counter of my own kitchen. They were gone, and yet they permeated my memory and my life. I’ve never forgotten Sheila and Kate, and I’ve never stopped talking about them.

Fourteen years ago here in Salon I wrote this about Sheila and Kate:

“It was traumatic; their disappearance spooked me horribly.… The day they ran the dogs in the woods across the street, the day they dragged the pond searching for their bodies, those are two of the most vivid and horrific memories of my youth. I worried for my life, that I would disappear or that I would be killed. I started writing my will. I was 6.

One of the other theories surrounding the girls’ disappearance was that they had been sold into ‘white slavery.’ While I didn’t know what this was, I intuitively knew it involved sex. Adults did not so much as pause before discussing the kidnapping of the girls and the possibility that they had been murdered, but their hushed tones and grim faces when ‘white slavery’ was mentioned made me know it was about sex. And I could tell that it was something bad, shameful, and not to be talked about. Yet it was something being done to me all the time.”

I’ve always been drawn to missing girls, to girls not being heard. In part, it was my own experience with being abused — but it was because of the Lyon sisters, too.

I didn’t tell anyone about my abuse until I was in my early 20s. Some years later through the police I was put in touch with victim advocate John Lyon, Sheila and Kate’s dad, who had gone to work for the legal system helping crime victims. He was so kind to me. He offered to meet with me any time, congratulated me for coming forward, no matter what came of it, and let me know whatever decisions I made were okay. I closed my eyes when we talked on the phone and I heard his smooth, booming radio voice, transported back to 1975 all over again. He didn’t know me by my married name, and out of fear of upsetting him I didn’t bring up the connection my family had to his, or anything about Sheila and Kate, but I was struck by the way we were once again connected by the sexual violence of men toward young girls, and rattled as the past came vividly alive all over again. As Faulkner wrote,”… no such thing as was — only is. If was existed, there would be no grief or sorrow.”

As a child, I had been afraid to tell what was happening to me, about the abuse. Afraid I’d be hurt; afraid I’d not be believed, that nobody would listen. And in the case of the Lyon sisters, it turns out, nobody really listened to the girl who did come forth.

***

I wanted to find that girl, Darlene. From the moment last year when I learned that a girl had helped create a sketch that was both a dead ringer and almost entirely dismissed, I wanted to talk to her, to tell her how brave she was and how tremendous the information she’d given the police had been. I wanted to thank her for coming forth 40 years ago. I wanted to tell her how sorry I was that the information she gave – a nearly perfect description of the man who would go on to be indicted for the murder of the Lyon sisters – had been ignored for 38 years.

I was able to locate Darlene and spoke with her by phone recently, and we have corresponded by email. She told me that on that day in 1975, the man we now know as Lloyd Welch was “just beaming on them, and walking too close to them. It caught the eyes. I didn’t say anything to them but I said to him, ‘Take a picture, it lasts longer.’ I knew there was something wrong with him, I knew he was a creep.”

Thomas Welch, a cousin of Lloyd Welch’s, recently told police that he saw two girls he believes to have been the Lyon sisters alive at the home of Richard Welch, Lloyd Welch’s uncle, on March 30, five days after the were abducted. Richard Welch remains “a person of interest” being actively investigated in the case. Another relative of Welch’s recently told police that Richard Welch said that he and other family members sexually assaulted the girls on pool tables in Richard Welch’s home. The police believe that Sheila and Kate may have been alive for up to three weeks before being taken to Virginia and killed.

If the sketch created on March 27 of Lloyd Welch based on Darlene’s description had been disseminated widely, certainly police would have noticed how closely it resembled Welch when a week later, on April 1, 1975, he failed a police polygraph after telling authorities he had witnessed someone else abducting the girls. But the police officers who met with Welch that day apparently hadn’t seen the sketch, and therefore couldn’t see that Welch matched it perfectly, right down to the fringe of his hair, the curve of his nose and that unique scar on his left cheek. They sent him home.

By April 15, police believe the sisters had been killed, their bodies then stuffed in duffel bags and burned in a fire that witnesses recall filled the hills with the smell of burning flesh for days.

“As far as I know, they never released the sketch of Welch to the papers,” said Darlene. “I never saw it anywhere. The police all thought it was the Tape Recorder Man.”

A Jan. 13, 2015, affidavit police used to obtain a search warrant states, “The composite of the man [referring to Welch] was released via media outlets.” This, however, appears not to be the case. The Washington Post reports that the sketch of Welch made with Darlene’s description “appears not to have been widely disseminated.”

According to the Post, police grew more interested in a different suspect. Based on a description provided by a boy who had also been at the mall, they began looking for “a man said to be about 50, who was seen talking with the girls while holding a briefcase and a tape recorder. Police released a sketch of him to the media.”

Children from other neighborhoods also came forth and revealed he had been tape recording kids at other malls, too, around the same time. He was the primary focus of the investigation for years, but was never apprehended, and apparently never seen with his tape recorder in malls again.

***

We should, of course, applaud the efforts of the detectives who took the case back up in 2013, especially Dave Davis, who Darlene told me in our interview has given “110 percent since he came on and started talking to me in the last couple years.” According to Washington Post reports, immediately after joining the case in May 2013 he saw that the interview with Welch from April 1, 1975, was worth further investigation. Too bad the police in 1975 didn’t see it. Perhaps the Lyon sisters could even have been saved, and other girls spared his violence. As Darlene said, “It is very sad they didn’t catch him before he raped those other little girls, very sad.”

Even if the police hadn’t caught Welch in 1975, if they had investigated the sketch just enough to get a name and then annually checked his name against a criminal database, they would have discovered he was convicted of a sex crime against a child in 1994. It wouldn’t have saved Sheila and Kate, but it might have brought Mr. and Mrs. Lyon some peace decades earlier. Instead, the police ignored it

Talking to Darlene made me furious at all the police officers on the case who had made self-congratulatory remarks over the years about working every lead and tracking down every tip. I do not believe they did. We tell kids to come forward with the stories and then we pick and choose what to believe. We want to believe our cops are infallible heroes, but we know that all too often they are the opposite. We want to believe certain things about perpetrators — that they fit a certain profile, not that they are monsters among us and those we know and love but rather somehow other.

We also want to believe certain things about victims who deserved to be saved: that they’re innocent or naïve, as investigators called Sheila and Kate, girls who weren’t using drugs or having sex. They were good girls, worthy of our attention. Did the police think Darlene wasn’t naïve enough to believe? Did they decide her story wasn’t credible because she was so bold as to confront Lloyd Welch that day at the plaza, something a “nice girl” wouldn’t do?

Did they dismiss Darlene’s concerns about Welch as inconsequential because they decided that she might just be complaining about the sort of “normal” male attention girls would receive?

There are so many ways we dismiss the truths women and girls tell us, so many times we look the other way rather than confront their truths. We’ll never know the exact subtle ways and whys the police ignored the solid testimony she gave, what reason they conjured, consciously or subconsciously, for simply tucking her sketch into a file and burying it with the weight of the Tape Recorder Man for all those years. Women and girls are always too much, never enough. There is always some reason why their words are dismissed.

***

My life has been, in some ways, a shrine to silenced girls and women, to the Lyon Sisters, to the Darlenes, to trying to make sure the voices of women and girls are heard and respected. I’ve worked my whole life on these issues — at a rape crisis center, helping to start a national sexual violence hotline, volunteering to help create a writing program for incarcerated teens, most of whom were themselves abuse victims. I’ve worked on women’s international human rights and on bolstering assorted programs for the health and empowerment of women and girls and in support of fair treatment of women writers. In my own writing, too, I have focused on women and girls, on our stories, on the ways we are harmed, on the ways we are silenced and on our own power to change those things, on our ferocious strength.

Even as Welch is indicted for the murders of Shelia and Kate, I’m still trying to raise girls’ voices, to shine light on Darlene’s story, to make sure Sheila and Kate’s truths are told, that we pause to consider their suffering. Even now, I’m still hoping we’ll all listen. Welch’s indictment is a reminder to listen to girls and women and to trust them — and a reminder that the fight continues.

The world is a better place for women in some ways than it was in 1975; in other ways it is not. We still don’t listen to women and girls. We still have bogus notions of who does and doesn’t sexually assault women and girls. We still close our eyes to overwhelming evidence — as the recent Cosby case, among many others, demonstrates — and wait far past the point of reason to face harsh realities. This is still the world where I knew not to speak up against the man who abused me when I was a child. Still the world where every day women and girls are not believed and are told in myriad ways to keep quiet because if they do speak up they will be shamed, they will be harmed.

Some might ask what difference does all this make now, when the Lyon sisters are dead and a man has been charged? It matters to honor Sheila and Kate, to look closely at what happened, to consider their suffering, to consider the possibility of them being repeatedly raped for weeks while the police disregarded the description of the man who allegedly abducted them. It matters for the girl who came forward and was ignored for all of those 38 years, to let her know she is a hero. It matters for all of tomorrow’s raped and murdered girls. It matters if we are ever going to change.

In story after story from the time, the accounts of boys are repeated and repeated, while the girl who gave them the composite sketch that correctly portrayed the man now charged with murder was erased from every story about the case until last year. We need to think about how we listen and don’t listen to women and girls. Let’s make sure that this truly is Operation Worthy Cause, as the police termed their recent investigation into the case. Let’s make sure for Sheila and Kate, for Darlene, for the next girls who go missing, for all of us.