Often the opinion articles you see in the daily newspaper should be described as a form of lobbying. The author becomes a third-party validator for powerful people, transmitting their policy arguments in a somewhat more subtle fashion.

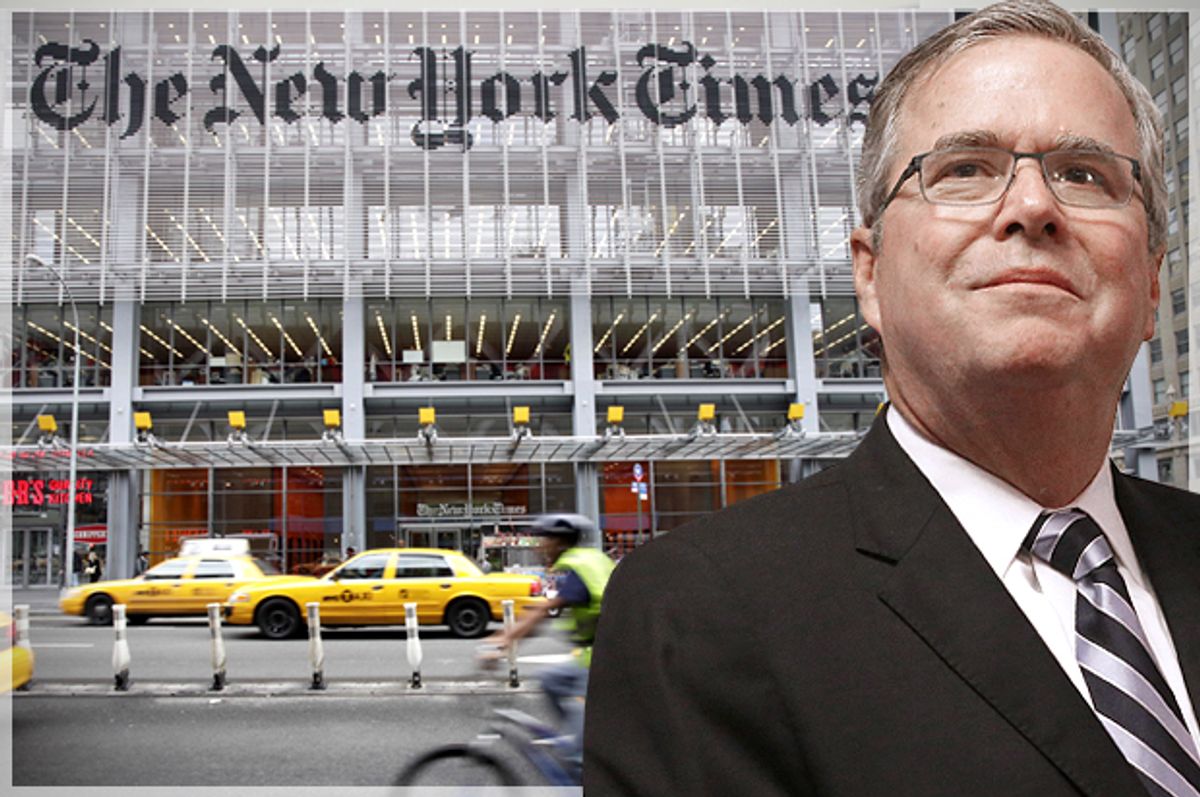

This is what Andrew Ross Sorkin is up to, perhaps unconsciously, when he spends two-thirds of an article on Jeb Bush’s tax proposal, demonstrably a wet kiss to the wealthiest Americans, by marveling about how it hurts the private equity titans who have given Bush campaign donations.

Sorkin eventually gets around to telling the whole story about Jeb’s tax cuts. But before that, he captures in lurid detail a $4 million fundraiser for the former Florida governor at the home of private equity kingpin Henry Kravis, and wonders how Jeb could “take a direct shot at the very people who filled the tables that night to support him.” This gives Jeb’s proposal entirely too much credit.

Sorkin identifies two anti-Wall Street provisions. First, Bush would close the carried interest loophole, which hedge fund and private equity managers exploit to treat large parts of their income as capital gains, earning a lower tax rate. You can’t really assess this without noting that Bush also lowers the top marginal tax rate from 39.6 percent to 28 percent.

Currently, to avoid that top rate, Wall Streeters taking advantage of carried interest pay 23.8 percent in capital gains taxes on that earned income. But under Bush’s plan, the rate would only go up to 28 percent, a far less drastic scenario than if the top rate were still at 39.6 percent.

And then you have to take into account all the other goodies the rich get from Jeb’s tax cuts. According to a Citizens for Tax Justice study released Tuesday, 53 percent of the $227 billion in annual income tax cuts in the plan go to the top 1 percent of earners. That doesn’t take into account the slash in corporate tax rates, three-quarters of which the congressional Joint Committee on Taxation says goes to owners of capital, in other words the wealthiest Americans. And Bush would eliminate the estate tax, a sop in its entirety to the same elite class. He even kills the alternative minimum tax, which would also shield the well-off from paying more.

Once you factor all that in, the 4.2 percent increase from closing the carried interest loophole looks more like a love tap than an attack.

The second measure that Sorkin devotes lots of space to as an example of Jeb turning his back on private equity would end the deductibility of corporate interest payments. He is not the only one to bring this up as a bombshell. Tim Worstall of Forbes says it would “completely change the structure of current capitalism,” destroy the corporate bond market, eliminate business lending by banks and make it impossible to develop property.

These are apocalyptic claims. And it’s true that this provision really would change how businesses are funded, probably for the better, by prioritizing equity over debt. As Sorkin notes, the leveraged buyout industry loads companies up with tax-preferred debt to suck value out. This serves as a form of financial engineering, increasing profits at the expense of firms and their workers, and we should celebrate anyone trying to alter that dynamic. It really could “help address many of the big challenges that our debt-fueled economy has created,” as Sorkin writes.

But once again, we must read the fine print. First of all, Sorkin points out in an aside halfway through that the interest-deduction plan “has one large exception: banks.” And excessive borrowing from banks just happens to be a significantly dangerous threat to the economy, maybe the single item that transformed the housing bubble collapse into a broad financial crisis. If you were going to eliminate the deduction on interest for any industry at all, arguably the first one would be banks, if you were concerned about economic safety and soundness.

The real estate industry and private equity, through less attractive leveraged buyouts, would be most harmed if they couldn’t increase profits by taking on tax-deductible debt. But if banks are exempt, you can see precisely the kind of game-playing we always see from clever Wall Street lawyers, routing loans through banks or having real estate or private equity concerns purchase a small savings and loan to make their debt eligible for tax breaks. Under Dodd-Frank’s “Volcker rule,” for example, banks can sponsor private equity firms with a limited investment, potentially providing a wedge to transfer the debt payments to the bank.

There’s also the point that businesses will be able to immediately deduct the full value of their capital investments. So large businesses, which don’t gather much benefit from the deduction of interest payments anyway, get a large gift to supplant that benefit and move forward.

It is kind of interesting that Jeb would add features to his tax plan that bite the private equity hands that feed him, at least in Sorkin’s view. But when you factor in all the largesse the super-wealthy get from the plan, they’ll end up far better than under the status quo. Just ask, well, The New York Times, in places other than Andrew Ross Sorkin’s column.

The Sorkin piece, combined with other articles that make similar points, constitute a kind of elite signaling, expressing displeasure with facets of the Bush tax cut plan, in the hopes of catching a sympathetic ear inside the campaign. The Wall Street Journal even included a quote from the Private Equity Growth Capital Council, complaining that “increasing taxes on carried interest would discourage growth and investment, and would make our tax code more complex and less fair.” This is called working the refs, and if Bush quietly changes the provisions private equity doesn’t like, we’ll know it worked. And Andrew Sorkin can become less frazzled that their contributions at Bush fundraisers didn’t meet their intended goals.

Shares