Over the last few months, various factions on the left side of the political spectrum have been in heated debate on the comparative merits of Bernie Sanders and Hillary Clinton. The debate has increasingly gotten rather shrill, not unlike the Obama-versus-Hillary discussion in 2008. Bernie supporters are called “mansplainers” or “brocialists” whilst Hillary supporters are decried as neoliberals or establishment shills.

On the one hand, it’s not helpful to pretend that Bernie and Hillary are the same, nor to pretend they would govern the same. However, far more interesting than litigating their differences would be to analyze the constraints they would face in implementing a progressive agenda -- and shift those constraints in a leftward direction.

A recent Ryan Lizza profile of Elizabeth Warren includes an important anecdote that highlights how Clinton would act as President:

They met alone for half an hour, and, according to Warren, Hillary stood up and declared, “Well, I’m convinced. It is our job to stop that awful bill. You help me and I’ll help you.” In the Administration’s closing weeks, Hillary persuaded Bill Clinton not to sign the legislation, effectively vetoing it.

But just a few months later, in 2001, Hillary was a senator from New York, the home of the financial industry, and she voted in favor of a version of the same bill.

That is, if Lizza’s reporting is correct, Hillary in one context effectively vetoed a bill and in another voted in favor of it. This suggests that focusing on Clinton’s motives and personality is far less important than the political constraints she faces.

We can see something similar when examining Bernie Sander’s position on guns. Over at Vox, German Lopez explains it this way:

Sanders's record isn't atypical for a Vermont Democrat. Although the state is very liberal, its rural culture makes it unusually moderate on guns. As Anthony Pollina, Sanders's chief of staff at the time, told the local news outlet Seven Days in 1991, "Bernie's response is that he doesn't just represent liberals and progressives. He was sent to Washington to present all of Vermont. It's not inappropriate for a congressman to support a majority position, particularly on something Vermonters have been very clear about."

And indeed, as Bernie has run for national office, he has moved more in line with mainstream Democratic stances on guns, as would be expected. In a recent New Yorker profile of Bernie, Margaret Talbot discusses his rather successful time as Mayor of Burlington:

Yet Sanders turned out to be a popular and effective mayor, and more pragmatic than some might have predicted. True, he travelled to Nicaragua, where he met with Daniel Ortega and found a sister city for Burlington. (Vermont reporters dubbed the mayor and his coalition the Sandernistas.) But he also presided over economic development that transformed the city into a hipper, more forward-looking place—one of those small cities that appear on lists of the most livable. And he did so without the kind of wrenching gentrification that he abhorred. His administration devised creative solutions for preserving affordable housing, including a community land trust that enabled low-income residents to buy homes. It became a model for other cities.

A key to his success then, was working within the structure of the office, but also pushing those structures outward. Such calculus is not limited to Democrats. On the other side, history tells us that Nixon signed into law quite a few good bills that he disliked, because he was a conservative president in an overwhelmingly progressive environment. Reagan signed into law the Therapeutic Abortion Act, not because Reagan supported abortion but because he knew his veto would be overrode, and felt that he could weaken the bill.

Now, acknowledging political constraints can often be a cop-out. People tend to see constraints to policies they don’t particularly like, and reject constraints with regards to those that they do. We should hold leaders accountable, and often leaders duck behind non-existent constraints as cover. But if we believe, as many do, that “Hillary changes with the wind,” then it’s a damn good idea to change the wind.

There are two key constraints that policymakers face: First, they need money, and second they need votes. Both of these necessities currently push them towards policies that progressives dislike, but this is not inevitable and with better policies, we can force politicians to be more responsive to average Americans, rather than elites.

Money:

The increasing importance of money in elections has been bad not only for Democrats (careful political science suggests money has helped Republicans at both the Presidential, congressional and state level) but for the broader progressive movement. The chart below from political scientist Christopher Witko’s essay in Matt Grossman’s "New Directions in Interest Group Politics" shows how as Labor’s share of contributions to Democrats has increasingly been replaced by Corporate, Trade, Membership and Health, policy-making has grown increasingly conservative.

Though this is merely correlation, there are reasons to believe there is a causal link. First, there is the extensive narrative work of political scientists like Paul Pierson and Jacob Hacker, who have documented how the race for money pulled Democrats away from progressive policy. Witko and Adam Newmark find, “the dominance of a state's campaign finance system by business interests makes policy more favorable toward business.”

There is other evidence to suggest that the increasing reliance on the donor class has pulled both parties away from economically progressive policies, and also hampered efforts towards racial justice.

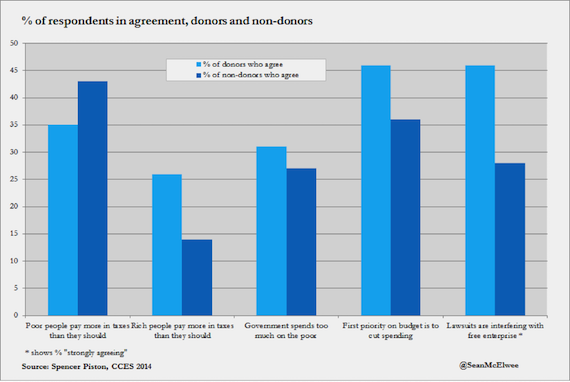

The chart below is created with Cooperative Congressional Election Studies (CCES) 2014. The political scientist who ran the numbers for Salon, Spencer Piston of the Campbell Public Affairs Institute at Syracuse University, says the data indicate “donors are more likely than non-donors to oppose the downward redistribution of wealth.”

The solution is a robust public financing system. After public financing was put in place in Connecticut, one legislator reported, “Before public financing, during the session…there were ‘shakedowns’ where lobbyists and corporate sponsors had events and you as a legislator had to go. That’s no longer a part of the reality.”

Voter turnout:

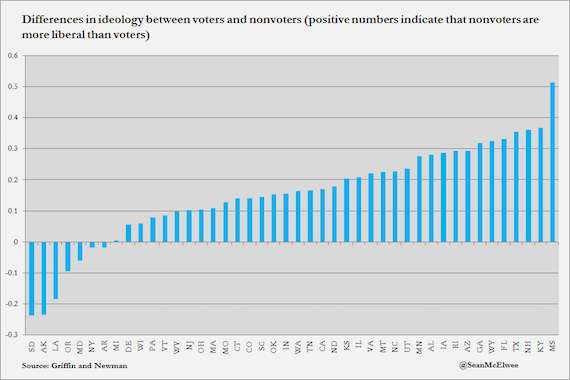

Policymakers want to get elected, and re-elected. However, as political scientists Brian Newman and John Griffin note, voters are “almost always more conservative” than nonvoters and “in states where voters are more conservative than nonvoters, Senators tend to be more conservative.”

The chart below shows that there only a few states where voters are more progressive than non-voters. Why does this matter? In my recent report, "Why Voting Matters," I argue that turnout would lead to more progressive policy. I cite state level, international and historical evidence to bolster the claim that higher turnout leads to better representation and more progressive policy.

The problem with the United States' low turnout is that it serves to exacerbate the power of the donor class. Political scientists Steven Rosenstone and John Hansen note that, “class difference in mobilization typically aggravate rather than mitigate the effects of class differences in political resources.”

As the chart below, from my last piece, shows, the unregistered population is far more supportive of a $15 minimum wage than the registered population. A politician considering a $15 minimum wage in a United States with 40 percent turnout is far less likely to pursue the policy than a politician in a world with 80 percent turnout.

To bolster turnout, we need robust enforcement of the National Voter Registration Act, automatic voter registration and same-day registration for voters who aren’t registered automatically at the DMV. In addition, we need non-partisan get-out-the-vote mobilization, and an abolition of all restrictions on the voting rights of former felons. We need to restore the VRA to stop racially-charged voter ID laws and proof of citizenship laws.

The policies above are aimed at only two of many ways to shift the political calculus of politicians. As I’ve noted, increasing representation for women, people of color and working class Americans is important. In addition, a key mechanism by which power operates is by constraining what policies are even considered. Indeed, the right has exploited the fact that the mainstream media, in its attempt to remain “non-partisan” has allowed the right to subtly shift the field of discussion. The two major lawsuits against Obamacare for instance, went from being insane legal challenges accepted only on the fringes of the right to something that John Roberts is now openly decried as a RINO for rejecting. The primary purpose of the right-wing media is to legitimate Republican extremism.

Further, the solutions I’ve discussed don’t even begin to discuss the other questions the left needs to answer (what is to be done at the state and local level?) nor the tactics available (sit-ins, organizing, direct action, marches, lawsuits). The Fall issue of Dissent, highlighting debates within the left, begins to answer these questions, and the political journal Democracy's Fall issue has included a fascinating essay by Alexander Hertel-Fernandez and Theda Skocpol on how progressives can gain power on the state level.

Further, what differences exist in the policy platforms of Bernie and Hillary (on higher education, banks and healthcare among others) are worth debating, and far more interesting than the relative loudness of their speaking voice. On the other hand, it’s worth remembering that many of the purported differences between Obama and Hillary existed on healthcare policy largely collapsed when Obama went to implement his plan.

How to re-energize the left and create independent political power for women, people of color and the working class is still an open question. How to shift the calculus of politicians, to get progressive policies on the agenda and to implement those policies is something progressives need to openly debate. These questions are far more interesting and important than which of two (rather similar) candidates will eventually be stymied by Republican intransigence. Further, who politicians will respond to, the people or the donor class, remains to be seen. The question at hand is not Hillary or Bernie, it’s whether America will be a democracy.

Shares