Somewhere deep in his past, Purdue University president Mitch Daniels heard some Presbyterian minister drone on about the biblical maxim that pride goeth before the fall. (The actual quotation from Proverbs, in the King James Version, is more complicated but says the same thing: “Pride goeth before destruction, and an haughty spirit before a fall.”) Little Mitch wasn’t listening, it seems. He was daydreaming about his golden future as the head of conservative think tanks and the president of Eli Lilly and George W. Bush’s budget czar.

If you follow politics (a bit more closely than you should), you will remember Daniels as the union-busting, budget-cutting governor of Indiana who was briefly auditioned by GOP sages like Ross Douthat and David Brooks for the role of “sensible Republican” in the 2012 presidential campaign. Last week he created a tiny news moment by issuing a bizarre statement praising his stolid Midwestern institution for its student-endorsed free speech policy and for avoiding the racial turmoil that has erupted at the University of Missouri and Yale and various other campuses across the country. “What a proud contrast” Purdue offered, he said, “to the environments that appear to prevail” elsewhere. Within a few hours, of course, student activists at Purdue announced that they would walk out of classes on Friday afternoon and stage a rally in solidarity with the Mizzou protesters.

By the time that gathering at the home of the Boilermakers actually happened, dreadful news from Paris had driven the “Chaos on campus” – as Fox News described it last week – out of the headlines. A startling number of conservatives, missing no opportunity to make an unrelated tragedy be about them, used the Paris attacks to bash student activists: Apparently, if you’re not being shot at by murderous fanatics, you have no right to protest about anything ever. The hypocrisy and narcissism of this position are boundless, especially when you consider the tradition of the French university, whose students nearly brought down Charles de Gaulle’s government in May 1968 and remain ready to stage militant protests over a 10-cent rise in the price of espresso at the campus cafeteria.

In fairness, the campus turmoil of fall 2015 – the “prevailing environment” that Mitch Daniels so artfully declined to characterize -- is bewildering to all facets of the political spectrum. One thing we can say for sure is that it has the right wing freaking the hell out. Fox News’ Friday counterattack also featured Alan Dershowitz, the right’s designated civil-liberties defender, declaiming that while student protesters claimed to value diversity, they refused to engage with a “diversity of ideas.” Staking out the position of maximum obnoxiousness, as always, a Wall Street Journal editorial described the Missouri and Yale protests as a “children’s revolt” and extolled Daniels as one of the few “grown-ups on American university campuses.” Behind the sneering you can feel the fear, and I have no problem with the knee-jerk position that whatever terrifies the WSJ is likely to be a good thing in the long haul.

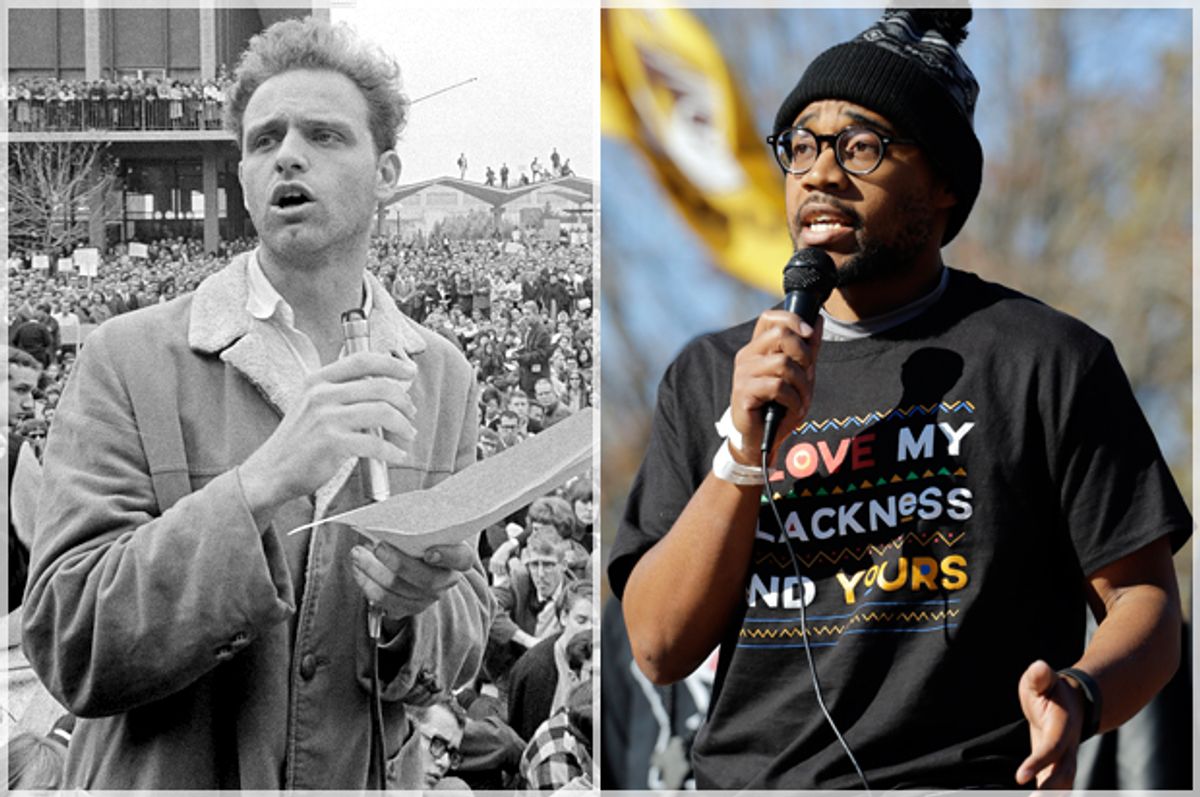

We’re a fair distance yet from the legendary student uprisings of the past. The Mizzou moment is not Paris ’68 or the Free Speech Movement at Berkeley or the waves of anti-Vietnam protests that led to the student takeover at Columbia and the campus bombings in Madison and the shootings at Kent State. At least not to this point. But conservatives are so vigorously demonizing the current student unrest because the Mizzou mood has spread so rapidly and uncontrollably. It would be foolish to predict how far it will go or where it will lead.

If nothing else, it is finally time to retire the insidious media cliché that college students are inherently apathetic or overly materialistic or more conservative than their parents, which has been rolled out in various forms for every matriculating class since the Carter administration. As with so many political truisms, there was an element of truth to that during those decades. But there was also an element of ideological suasion, and a not-so-subtle attempt to cast all youth activist movements as ridiculous when compared to their illustrious forebears. Whatever the proximate issues were – nuclear weapons, Take Back the Night, apartheid, the Israeli occupation, LGBT rights – reporters nurtured on Boomer mythology showed up on campus for 20 minutes and announced that it was all a pale imitation of the ‘60s.

Between the explosion of Missouri-style protests over race relations that have largely (but not entirely) been led by students of color, and the Bernie Sanders socialist revival that has largely (but not entirely) been driven by white students, we have unexpectedly encountered the most energized and radicalized campus population in at least 40 years. As with the Vietnam War movement, and more recently with the campaign to recognize and address sexual assault on campus, the Mizzou moment has spread to different kinds of institutions in all parts of the nation, from bucolic liberal-arts colleges to big land-grant universities to elite Ivy League schools.

Any list I try to compile is likely to be outdated by the time you read this, but after the protests at Missouri and Yale made headlines, the president of Ithaca College in upstate New York and a dean at Claremont McKenna College in Southern California were targeted by protesters who believed they had mishandled racial episodes. (The Claremont dean resigned, while Ithaca’s president is hanging on for now.) Students at Georgetown University in Washington, D.C., and Smith College in Massachusetts staged demonstrations demanding that administrators address racial grievances, while two traditionally black colleges in the Washington area, Bowie State and Howard University, became the targets of apparent racist threats or vandalism.

I brought up Mitch Daniels not just to make fun of a smug and clueless Republican, although that’s fun too, but because his smugness and cluelessness is a generalizable ailment found among the college administrator caste, and is precisely what is fueling the student uprising. Daniels assumed that Purdue was immune to this activist virus because it’s a squaresville school in the middle of Indiana, and because he had held some pro-forma meetings and published some boilerplate rhetoric on university letterhead. That assumption was a symptom of the underlying problem that has driven these protests, rather than any part of the solution.

Any outsider, and especially any white media commentator (ahem), runs the obvious risk of tumbling into the Daniels gap the moment we pronounce that we understand what’s going on in the tumultuous campus fall of 2015. Indeed, that’s the crux of the matter: On campus after campus, black and brown students are telling us that they will not put up with being condescended to or lectured at by clueless white people who think they have it all figured out.

I think it’s important to develop that idea a bit more. I’m not saying that I relinquish my right to hold opinions because I’m a white dude who attended college when Ronald Reagan was president. I mean, Jesus – here I am, week after week, with the immense privilege of inflicting my opinions on thousands of readers. It’s entirely likely that in some of these cases I would feel that the student protesters were being unreasonable or oversensitive or allergic to nuance or intolerant of free expression. I have highly predictable views for a person of my background and occupation: I’m opposed to censorship in any imaginable form, and I don’t believe obnoxious forms of speech or offensive Halloween costumes should be criminalized. (As far as I know, no one has actually suggested they should be.)

Well, OK. But in the first place, heaven forfend that young people should be angry or intemperate or unrealistic, because that’s never happened before. In the second place, my feelings, and Mitch Daniels’ feelings, and the feelings of that Yale faculty couple who are no doubt liberal Democrats and civil-rights advocates and thoroughly lovely people and who have been cast as campus villains by the protest movement, are precisely and specifically not the point. As for all the media hand-wringing about whether these emerging student activists hate the First Amendment and want to impose Stalinist speech codes and might be better off hitting the books for a little Enlightenment philosophy – well, that’s not entirely missing the point, but it’s also not all that helpful.

Confronting institutional racism or racial grievances on campus, and dealing with the long legacy of white supremacy that informs unequal access to education and unequal outcomes, is one of those areas where competing aspects of progressive or liberal ideology collide with each other. How we strike a balance between rights and freedoms – between the principle of equality and the principle of liberty, the twin ideological pillars of Jeffersonian democracy -- is in question throughout the Western world. That problem was thrown into sharp relief this weekend by the events in Paris and their aftermath, which revealed once again that America’s so-called conservatives actually support neither liberty nor equality (or at any rate do not see them as universal).

When values of pluralism or multiculturalism intersect with values of free speech or free association, we often find ourselves genuinely confused about how to respond. The confusion is honest, and the conflicts cannot all be painlessly resolved. If we stood with #JeSuisCharlie after last January’s attacks, did that mean we endorsed Charlie Hebdo’s mocking caricatures of the Prophet Muhammad? Should “Lolita” and “The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn” and “Leda and the Swan” carry trigger warnings, or be excised from the curriculum as inherently hateful and oppressive acts? Should we stop using the adjective “niggardly,” because it accidentally resembles another word?

That one is instructive, in a way. Along with roughly 100 percent of the media, I thought that controversy was ludicrous when it came up in the late ‘90s and early 2000s: If we consult the dictionary, we learn that “niggardly” can be traced back to Middle English and Old Norse, and has no etymological connection to the racial slur. But I have to say that my perspective has since shifted. We pretty much have dumped that word, because it is so easily misunderstood and other words will do, and also because it carries a permanent taint: The only person who would conceivably use it now would be a snickering, anti-p.c. asshole trying to make an obnoxious point. Do we miss it? I submit that we don’t.

My point is that these conflicts almost always have a highly subjective character and that people will feel different ways about them at different moments. Furthermore, and far more important, the immediate impulse to get up on your high horse and explain to other people why they’re wrong to be angry or offended is never a good idea. I’m inclined to believe that Nicholas and Erika Christakis, the Yale faculty couple, had no malign intentions and have been pilloried over a minor misunderstanding, while Mitch Daniels is an unctuous hypocrite who has spent his life surfing the tides of high-end capital and deserves every possible humiliation. But my beliefs about them are irrelevant, because they both committed exactly the same unforced error: They assumed that from their enlightened perspective they understood the world, and the students at their own institution, and they were wrong.

As Meghan O’Rourke of the New Yorker has written, the email from Erika Christakis that sparked a furor at Yale was not “all that well judged or intellectually useful.” Yale administrators had not actually forbidden any particular Halloween costumes, or punished any student for wearing one. They had sent out an email suggesting to students, “Don’t be a Halloween troll,” in O’Rourke’s words, “and Christakis chose that moment to advocate for the free-speech rights of trolls.” Yes, trolls have free-speech rights, and should continue to have them even in the context of an elite residential college. But Christakis came off as lecturing rather than listening, as a clueless white person who was instructing students of color how they should feel about the peculiar nature of their institution and the painful legacy of racism. In other words, she failed to perceive how she would be perceived, which lies at the heart of every generation gap.

It’s not remotely accidental that the unexpected activist wave of 2015 coincides with a number of other social and political crises. Worsening economic inequality, driven by decades of bipartisan “austerity” politics, has hardened into a caste system -- and has saddled many of today’s college students with unmanageable levels of debt. As the psychotronic presidential campaign has already demonstrated, the Republican Party has collectively fled into delusional fantasy and outright racism. Meanwhile, the rudderless and mission-free Democratic Party has suffered widespread institutional collapse under Barack Obama, despite the supposed demographic advantage it has been promising itself for the last 25 years.

Democracy and capitalism are showing signs of major systemic failure, and the relative social peace of the last few decades – the peace fueled by ever-cheaper consumer products and the massive expansion of the prison-industrial complex – is beginning to crack open as well. Despite differing objective circumstances, there are parallels to the student activism of the ‘60s, in which large numbers of disillusioned young people rebelled against the condescending moral certainty of the World War II generation that had plunged the nation first into the Cold War and then into Vietnam.

While the baby boom children who became the student left of the ‘60s had grown up amid unprecedented affluence, today’s college-age young people have only known economic stagnation and diminished expectations. In both cases, we see emerging generations who are largely immune to the American mythology of endless prosperity and expanding freedom: In the first instance, they came to see it as a hollow and destructive ideology; in the second, they see it as entirely fictional. Both these radical moments reflect a widespread sense that America’s internal contradictions are drawing near an irreconcilable crisis. Are such radical moments sometimes incoherent or overly zealous or plagued by misjudgment? Well, sure. But instead of pontificating about the abundant errors committed by Young People Today, we might do well to look around us and consider where they learned such things.

Shares