"Let us burn this motherf__king system to the ground," writes Claire Vaye Watkins, "and build something better." Readers of the world, get the torches and gasoline.

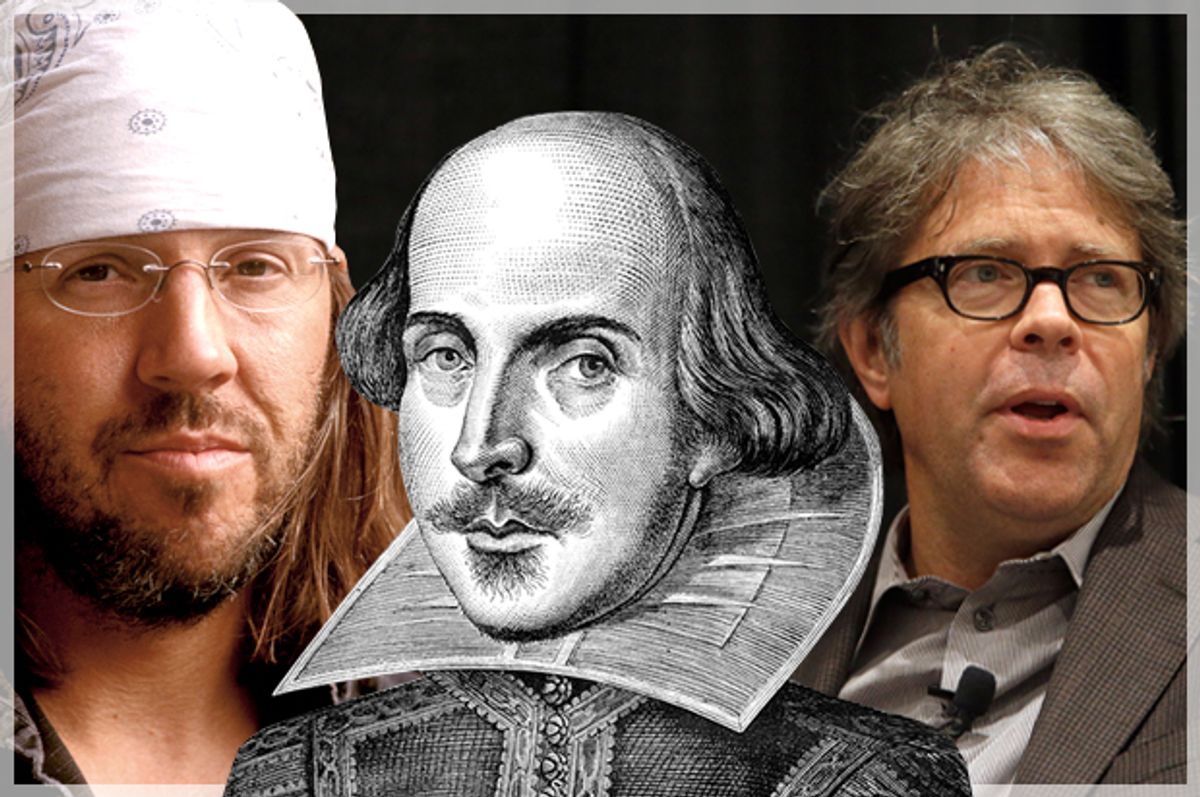

In a gloriously righteous Tin House essay "On Pandering" that is likely already tearing its way through your social media feed this week, the author of "Battleborn" and "Gold Fame Citrus" explores her own personal history as a reader of male writers and watcher of, as she puts it, "boys doing stuff." Along the way, Watkins shares a telling anecdote of what happened when "The Rumpus" editor Stephen Elliott came to town while she was in grad school, acknowledges her "invisible cloak of white privilege," and admits, "The stunning truth is that I am asking, deep down, as I write, What would Philip Roth think of this? What would Jonathan Franzen think of this? When the answer is probably: nothing…. I wrote 'Battleborn' for white men, toward them. If you hold the book to a certain light, you’ll see it as an exercise in self-hazing, a product of working-class madness, the female strain. So, natural then that Battleborn was well-received by the white male lit establishment: it was written for them. The whole book’s a pander."

And Watkins suggests, ultimately, that all of us shake out the "working miniature replica of the patriarchy" in our minds and "make our own canon filled with what we love to read, what speaks to us and challenges us and opens us up, wherein we can each determine our artistic lineages for ourselves, with curiosity and vigor, rather than trying to shoehorn ourselves into a canon ready made and gifted us by some white f__ks at Oxford." It's heady, crackling stuff.

In addition to its own strengths, "On Pandering" makes an exquisite sibling to Saeed Jones' fantastic piece for Buzzfeed earlier this year, "Self-Portrait Of The Artist As Ungrateful Black Writer," and Rebecca Solnit's recent LitHub essay, "80 Books No Woman Should Read." In hers, Solnit masterfully eviscerates Esquire's absurd list, from a few years back, of books every man should read. "Should men read different books than women?" she asks. "In this list they shouldn’t even read books by women, except for one by Flannery O’Connor among 79 books by men." She then proceeds to trim the fat from the Esquire list, noting, for example, that "Norman Mailer and William Burroughs would go high up on my no-list, because there are so many writers we can read who didn’t stab or shoot their wives." And in the end, she states what so many of us, male and female, have simply internalized as readers, that "Even Moby-Dick, which I love, reminds me that a book without women is often said to be about humanity but a book with women in the foreground is a woman’s book."

As the ever astute Jennifer Weiner writes in the Guardian this week, the problem isn't just limited to books that women write; there's a ghettoizing of books they read. Writing on critical scorn for lauded yet unforgivably successful recent novels, she notes, "And you, dear (female) reader, are ultimately the object of the Goldfinchers’ ire. The books you’ve insisted on making popular are bad ones: sentimental, mawkish and manipulative. You’re a dim bulb, a fumbling, rattle-grasping baby, unable to digest anything but the watered-down pablum that Tartt or Sebold or Yanagihira are serving; incapable, even, of correctly determining whether or not you liked what you read."

I've thought a lot about this recent wealth of smart literary criticism lately. In a few months, I have a nonfiction book coming out, about my experience in a clinical trial. The word "science" even appears on the cover. Yet until I read Watkins' and Solnit's pieces, it honestly never once crossed my mind that there was anything unusual about the fact I'd just assumed men won't read it. I'm a woman; I'm a mother; my book contains a lot of scenes of crying. I didn't bother to ask any men to blurb it; I was mildly apologetic when I asked a few trusted male friends just to read it.

I realize that sounds a little casually sexist of me. And my evidence suggests that men read do books by women. Just last week, I went to an event in which "Blackout" author Sarah Hepola talked about her drinking memoir, and having male readers come up to her and say, "You told my story." I have sat on subway trains and spied men reading "Orange Is the New Black." But here's my point: I, a woman who writes about feminist issues on the daily, take for granted Solnit's observation that a book by a man will be greeted by the world as a book, and that a book by a woman — whatever the subject matter — will be greeted by the world as a genre work. I've got to do better, because stories about women are stories about people. Like Watkins and Solnit, I want things to change, one writer, one reader at a time. And I want to see a man on the subway, reading "Bridget Jones' Diary."

Shares