After important defeats in the last midterm elections and then again in off-cycle elections in Houston and Kentucky last month, many progressives are wondering what's gone wrong — and how the Democratic Party can get back on track.

A new working paper by Brian Schaffner and Stephen Ansolabehere, discussed for the first time here, suggests that higher turnout could be essential to securing more favorable electoral outcomes down the road. Their analysis involves the most comprehensive datasets that have ever been used to analyze the opinions of voters, nonvoters and presidential-only voters. They find that shifting the composition of the electorate could reshape American politics.

Most previous studies of voters and nonvoters use rich but small-sample datasets, such as the American National Election Studies surveys performed each election. While these sources are useful, they have two limitations: small samples of non-voters and over-reporting of turnout. To solve the problem, Schaffner and Ansolabehere use research from two sources: Catalist and the Cooperative Congressional Election Study Panel (CCES), a firm that purchases voter files and combines them with other relevant factors to aid political campaigns. Schaffner and Ansolabehere use a sample of nearly 3 million voter files from Catalist that cover the 2006, 2008, 2010 and 2012 elections. CCES us a 19,000-respondent survey performed in both 2010 and 2012. By using Catalist, Schaffner and Ansolabehere were able to validate turnout in CCES, meaning that they check a respondent’s voter file to ensure they voted. (They find that a whopping 63 percent of those who did not actually vote in 2010 reported that they did vote on CCES, which shows why the validation is so important.)

Registration is a key barrier

The first thing that the authors do is examine the distribution of the American population, by grouping them into core voters (who vote regularly in both presidential and midterm elections), presidential-only voters, midterm-only voters and nonvoters.

Using more than 2 million records, the authors find that only 25 percent of Americans voted in all four elections between 2006 and 2012. These Americans, who are disproportionately white, rich and old, have dramatically more influence over politics than nonvoters (who make up 37 percent of the population).

To reiterate: Far more people voted in zero elections between 2006 and 2012 than voted in all four elections.

Why do so few Americans vote? For the answer, we can turn to CCES data. (Though it has a smaller sample of nonvoters, these nonvoters appear representative of the population.)

CCES data suggest that 23 percent of of nonvoters in 2010 and 27 percent of nonvoters in 2012 said they didn’t vote because they weren't registered, the most frequently cited reason of all. Among those who only voted in presidential years, disliking the candidates, lack of information and busyness were the top reasons for not voting in midterm elections. Among the small group (4 percent) of Americans who only voted in midterms, busyness and disliking the candidates were the top reasons for abstaining.

Nonvoters matter

Both data sources suggest that core voters are older, whiter, richer and better educated than nonvoters and presidential-only voters. This leads to different partisan identification: nonvoters were mostly either Independents (30 percent) or Democrats (43 percent). Presidential-only voters tilt the most strongly toward the Democrats, with 53 percent saying they are Democrats and only 32 percent identifying as Republican.

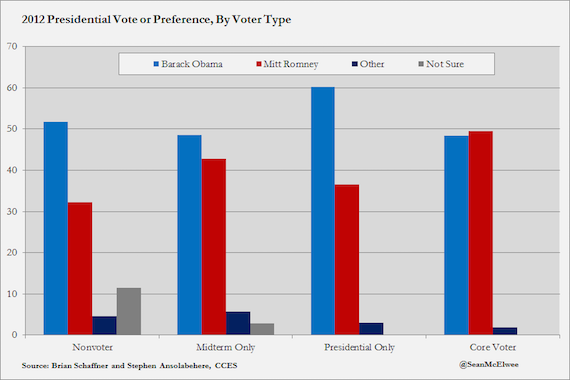

According to CCES, nonvoters prefered Obama to Romney by a margin of 52 percent to 32 percent, and presidential-only voters preferred him 60 percent to 37 percent. However, core voters preferred Romney over Obama, 49 percent to 48 percent. If presidential elections were decided by core voters, Romney might well have won.

In the 2010 midterm elections, nonvoters preferred Democrats 34 percent to 31 percent and presidential-only voters preferred Democrats 43 percent to 37 percent, while core voters favored Republicans 50 percent to 46 percent. The authors note:

“Adding the presidential-only voters to the 2010 electorate would have meant that the Republican margin would have shrunk to about a 3 point margin. Given the fact that there is more than a 1-to-1 translation of votes into seats in U.S. House elections, a 1 point difference in the overall Republican margin may have translated into a non-trivial difference in the number of seats won by Republicans.”

One natural experiment of the effect of turnout comes from the fact that some House elections occur in midterm years and others in Presidential years, meaning that half of elections have the more progressive electorates and the other half have a more conservative midterm election. A study by political scientist Anthony Fowler examines the impact of this divide on House elections. He finds that turnout is 13 percentage points higher when the election occurs in a presidential year. The higher turnout leads to a 1.5 percentage points higher Democratic vote share, and that translates into a 1.5 percentage points higher seat share. (Fowler tells Salon that such a shift would flip about seven races per year).

How to boost turnout

As I’ve argued extensively, most recently in my report "Why Voting Matters," higher turnout would lead to a more progressive and representative America. But how to do we get there?

The first solution to boosting turnout is clear: Registration barriers are the most important factor depressing turnout. Thus, robust enforcement of the National Voter Registration Act, expanded access to same day registration and more states adopting automatic voter registration will all boost turnout. Second, it’s clear that many voters are alienated by parties, and many see very few differences, which can depress turnout. Low-income Americans are the most likely to perceive large differences, possibly because parties overwhelmingly favor the preferences of the rich. Some have advocated Democrats pushing toward the center, but a working paper by political scientist Seth Hill finds that parties are far more successful in pulling in new voters than in converting swing voters.

The data from Shafner and Ansolabehere suggest there are millions of potential progressives who need to be mobilized -- but America lacks strong unions, which tend to mobilize the working class. This leads to a final way to boost turnout: nonprofits. A study released this week by Nonprofit Vote, "Engaging New Voters," finds that nonprofits tend to engage non-white, young, low-income and low-propensity voters. They find that when nonprofits contacted individuals, those people turned out at high rates, suggesting that nonprofits could dramatically reduce the class, race and age bias of the electorate.

As I’ve noted before, parties have reduced contacts to low-income people and many people of color and young people go ignored by campaigns because they aren’t registered. Nonprofits could step in and fill the void left by parties.

Using the most comprehensive dataset so far, Schaffner and Ansolabehere show that only about a third of Americans represent core voters. Given how much voting affects policy, and how unrepresentative these core voters are, this has significant implications for American democracy.

Schaffner tells Salon:

“There is no doubt that core voters look dramatically different than occasional voters and nonvoters, and to think that this does not have significant policy ramifications would be quite naive.”

Naive indeed, and yet a view held by far too many people who downplay the importance of turnout in forging a more progressive America.

Shares