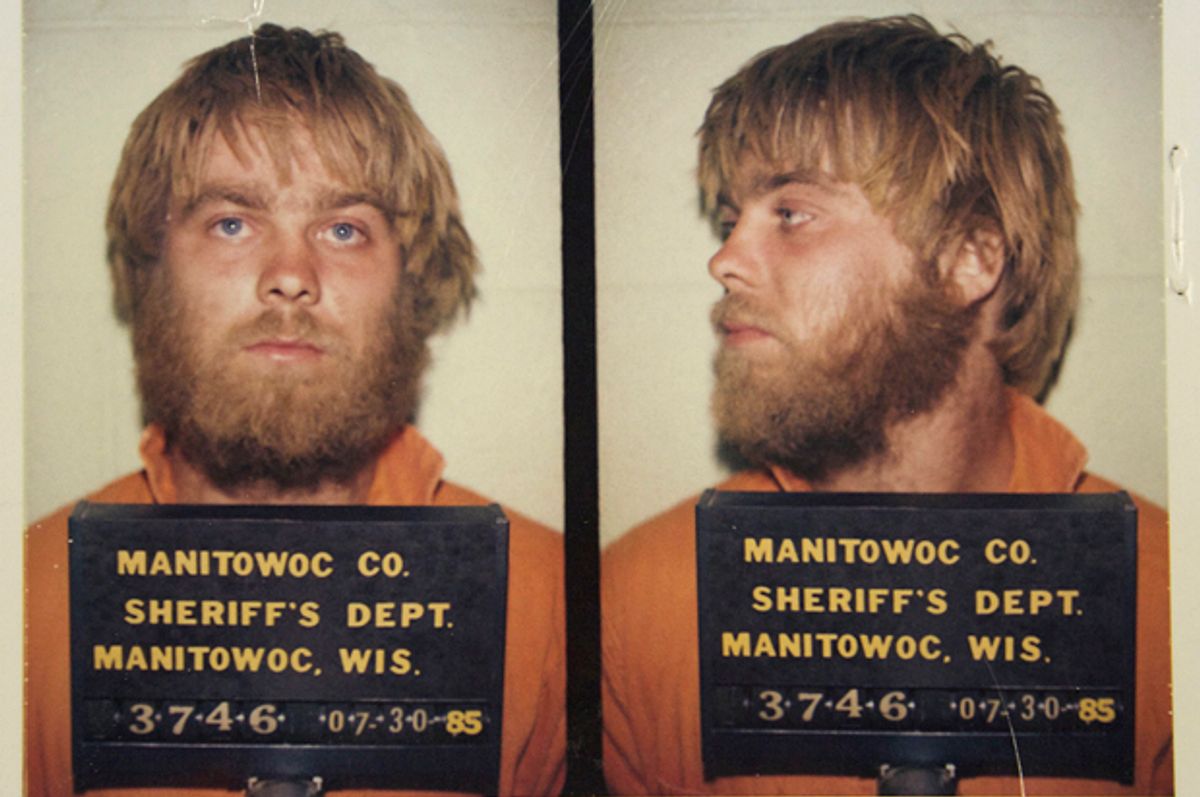

I sat down with my computer recently to stream an episode of "Making A Murderer," Netflix’s engaging and enraging true crime docuseries about Steven Avery, who may have been framed for murder—not once, but twice—by his small-town Wisconsin police department. More accurately, I’d planned to watch one episode; instead, I ended up watching five. That means for roughly five hours, I streamed one installment after another, unable to tear myself away even as the night wound itself into the wee hours of the morning. Before the credits were done rolling on each episode, I’d find myself clicking on the next, launching it before Netflix’s autoplay feature could even finish its 15-second countdown.

I sat down with my computer recently to stream an episode of "Making A Murderer," Netflix’s engaging and enraging true crime docuseries about Steven Avery, who may have been framed for murder—not once, but twice—by his small-town Wisconsin police department. More accurately, I’d planned to watch one episode; instead, I ended up watching five. That means for roughly five hours, I streamed one installment after another, unable to tear myself away even as the night wound itself into the wee hours of the morning. Before the credits were done rolling on each episode, I’d find myself clicking on the next, launching it before Netflix’s autoplay feature could even finish its 15-second countdown.

When it comes to this kind of obsessive series consumption, I’m definitely not alone. The term “binge-watch,” the shorthand descriptor for long periods spent watching, is so ubiquitous that Collins Dictionary declared it 2015’s “word of the year.” In September, Samsung offered a grant that would pay its recipient—some poor soul “unfortunate enough to have fallen behind on the latest TV series”—to spend 100 days doing nothing but binge-watch television. Netflix reports that nearly 75 percent of viewers who streamed the first season of "Breaking Bad" completed all seven episodes in a single session, a figure that rose to 81 and 85 percent for seasons two and three. And TiVo’s annual Binge Viewing Survey found that 92 percent of respondents said they had engaged in binge watching at some point in 2015.

Our love of television is well established, and has long been one of our most wildly popular national (and studies show, international) pastimes. But in recent years, there’s been a distinct shift in how we connect with the medium. That connection has grown so deep that many of us regularly find ourselves spending hours, days and entire lost weekends taking in our favorite shows.

In some ways, binge watching is simply the result of audiences taking advantage of new technologies that give us new ways of consuming our entertainment. Until the late 1990s, TV schedules were mostly dictated by networks. Your favorite show was likely broadcast once a week at a certain time, and if you missed it, you had to catch it in reruns. There were occasional marathons, when multiple episodes of a series would be re-aired, but watching back-to-back new episodes of a show was rarely an option.

Then came TiVo and other DVRs, DVD box sets, On Demand cable television, and finally, streaming services like Hulu and Amazon Prime. These innovations mostly allowed audiences to watch and rewatch beloved programs at their leisure. But it wasn’t until 2013, when Netflix made the groundbreaking decision to simultaneously release all 13 episodes of its first original series, "House of Cards," that binge watching really took off. Though the streaming site is notoriously mum about ratings, estimates suggest 1.5 to 2.7 million people watched “at least one episode the day after its release.” Those numbers helped support what Netflix’s own internal metrics and trendwatching had already gathered: people like to watch television precisely when they want, as long as they want. And demand is strong enough that if you provide plenty of supply, they’ll often watch far longer than they intended to.

We make time for the things we love, and TV is among the dearest of those. Americans spent increasing hours at work last year, yet studies show they also managed to squeeze in more television watching. While ratings for live TV— the old-timey “same time, same channel” sort—have been on a steady decline, online streaming and subscription services have only seen their numbers rise. An Adobe study of Americans’ television viewing habits found “total TV viewing over the Internet grew by 388 percent in mid-2014 compared to the same time a year earlier.” Given the option to watch television as our hectic modern schedules permit, we prove ourselves committed and voracious consumers.

In fact, a few months after its success with "House of Cards," Netflix released survey findings compiled by Harris International that further proved binge watching is not only commonplace, it’s the way we want to watch TV. Sixty-one percent of survey respondents—nearly 1,500 American adults who stream TV programs at least once a week—said they binge watched with regularity. Seventy-nine percent of those polled said “watching several episodes of their favorite shows at once actually makes the shows more enjoyable.” And 76 percent reported that “streaming TV shows on their own schedule is their preferred way to watch them.”

But binge watching isn’t just the end result of audiences having agency in when and how long they can watch. In some ways, the phenomenon offers yet more proof of what we already knew about our relationship with TV: that watching it just feels good. In their 2003 report "Television Addiction Is No Mere Metaphor," Robert Kubey and Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi found that TV has a soothing effect on watchers, offering an escape from their frantic workaday lives. (Seventy-six percent of participants in the Harris-Netflix poll said “watching multiple episodes of a great TV show is a welcome refuge from their busy lives.”) The researchers write that study participants reported they felt calmer and more relaxed “[w]ithin moments of sitting or lying down and pushing the power button,” and that “[b]ecause the experience of relaxation occurs quickly, people are conditioned to associate watching TV with rest and lack of tension.”

Kubey and Csikszentmihalyi also posit that television likely sparks our “orienting response,” an innate biological compulsion to coolly observe sudden sound and movement to assess for potentially harmful threats. They point to studies that suggest television, with its “cuts, edits, zooms, pans [and] sudden noises,” not only triggers this response, it may play a role in keeping us riveted. The evolutionary compulsion affects our entire physiology, causing “dilation of the blood vessels to the brain, slowing of the heart, and constriction of blood vessels to major muscle groups. Alpha waves are blocked for a few seconds before returning to their baseline level, which is determined by the general level of mental arousal. The brain focuses its attention on gathering more information while the rest of the body quiets.” Amidst so much physical stimulation, Kubey and Csikszentmihalyi suggest, may lie the reasons people often find themselves unable to resist looking at any blinking TV in their vicinity.

But we’re more than just our reptilian brains, startled into watching for hours by mere moving shapes and loud noises. A more complex neurological response helps explain not only why we watch TV, but why we find certain programs more compelling than others. The answer lies in neurocinematics, an emerging field of study that examines how our brains react to film and television and what kinds of storytelling captures our undivided attention. In his oft-cited 2008 study, Princeton University psychology professor Uri Hasson showed volunteers clips from "Curb Your Enthusiasm"; the late '50s TV show "Alfred Hitchcock Presents" ("Bang! You’re Dead"); Sergio Leone’s The Good, the Bad and the Ugly; and an unedited, one-shot video of a concert held in New York City’s Washington Square Park. Hasson and his research team were looking to determine “inter-subject correlation”—essentially, how much each clip successfully commanded the attention of all the participants involved.

MRI snapshots of subjects’ brains during screenings offered illuminating insights into our neurological response to both filmmaking methods and storytelling craft. Researchers found the Washington Square Park video engaged less than 5 percent of participants’ cerebral cortices and "Curb Your Enthusiasm" just 18 percent. Leone’s more cinematic The Good, the Bad and the Ugly fared far better, producing similar responses across 45 percent of watchers’ brains. But Hitchcock, as film students might predict, took the proverbial cake. The filmmaker’s clip “evoked similar responses across all viewers in over 65 percent of the cortex, indicating a high level of control of this particular episode on viewers’ minds.”

“The fact that Hitchcock was able to orchestrate the responses of so many different brain regions, turning them on and off at the same time across all viewers, may provide neuroscientific evidence for his notoriously famous ability to master and manipulate viewers’ minds,” Hasson et al. wrote in the summary of their findings. “Hitchcock often liked to tell interviewers that for him ‘creation is based on an exact science of audience reactions.’”

Hasson expounded further while speaking with Newsweek’s Andrew Romano for his 2013 piece, "Why You’re Addicted to TV." “In real life, you’re watching in the park, a concert on Sunday morning,” Hasson said. “But in a movie, a director is controlling where you are looking. Hitchcock is the master of this. He will control everything: what you think, what you expect, where you are looking, what you are feeling. And you can see this in the brain. For the director who is controlling nothing, the level of variability is very clear because each person is looking at something different. For Hitchcock, the opposite is true: viewers tend to be all tuned in together.”

It’s a lesson that networks, streaming service providers of original content, and TV writers have learned and embraced. In what is often labeled the new golden age of television, the shows so many of us binge watch, from Amazon’s "The Man in the High Castle" to HBO’s "Game of Thrones," have taken storytelling to the next level, creating taut, engaging narratives that keep us glued to our screens. Unlike the self-contained episodic shows of days gone by, the most watchable shows feature seductive, detailed story arcs that span entire series, which we want to trace from end to end. These programs are immersive and engulfing in ways far beyond shows of a generation before, which explains why we’re so often subsumed by the worlds they depict and why, for periods at a stretch, we’re hesitant to leave.

“When I started doing TV almost 20 years ago, studies showed that a so-called fan of a TV show probably saw one in four episodes on average,” Vince Gilligan, the creator of "Breaking Bad," told Romano. Networks in that era weren’t particularly interested in producing shows with narratives that required sustained, sequential viewing, since that posed problems when shows were rebroadcast, often in random order, in syndication. So plotlines were written to be neatly wrapped up as each episode came to a close. That contrasts sharply with today’s most binged-on shows, where storylines keep building and unfurling, necessitating start-to-finish viewing. “[Y]ou can imagine,” Gilligan told Romano, “with a serial like 'Breaking Bad,' someone watching one episode out of four would be pretty lost as far as what the hell is going on.”

Today’s binge-worthy programs require us to keep up, and of course, to keep watching. The availability of an entire series all at once is both a result of and a motivating factor in our tendency to keep viewing. Not only does it lure us into binge watching, it has made show creators tailor programming to our desire to binge.

“As bingeing becomes possible and commonplace, it’s only natural that shows should start to take it into account,” D.B. Weiss, a "Game of Thrones" writer, told Romano.

The result is a generation of shows that, like pageturner novels, make us nearly desperate to see what happens next. And writers make sure to ratchet up the action, intrigue and plot twists.

“Remember on 'Dallas' when somebody shot J.R.?” anthropologist and author Grant McCracken, one of the authors of the Netflix-Harris study, asked the Daily Beast. “If you found out who did it after the fact, what would be the point of going back and watching that season? But with something like 'The Wire,' even if a friend accidentally let a key character’s death slip it doesn’t really destroy the point of watching the show.”

“It’s like the people who make potato chips,” Carlton Cuse, a writer from the TV show "Lost," a forerunner of today’s must-watch TV, told Romano. “They know how to put the right chemicals in there to make you want to eat the next potato chip. Our goal is to make you want to watch that next episode.”

That “betcha can’t eat just one” approach to show writing is undeniably working. But here again, science plays a role in our tendency to binge. As Kubey and Csikszentmihalyi note in Television Addiction Is No Mere Metaphor, the relaxed feeling television provides has parallels with addiction. And like addicts, we’re loath to let those good feelings end:

A tranquilizer that leaves the body rapidly is much more likely to cause dependence than one that leaves the body slowly, precisely because the user is more aware that the drug’s effects are wearing off. Similarly, viewers’ vague learned sense that they will feel less relaxed if they stop viewing may be a significant factor in not turning the set off. Viewing begets more viewing.

What’s more, a 2015 study from the University of Texas at Austin found that those without self-control had a hard time stemming their binge watching. And that self control was harder to come by for people who were already depressed or lonely, who might turn to binge watching as a way to allay or distract from their negative feelings.

"Even though some people argue that binge-watching is a harmless addiction, findings from our study suggest that binge-watching should no longer be viewed this way," Yoon Hi Sung, one of the study authors, wrote. "Physical fatigue and problems such as obesity and other health problems are related to binge-watching and they are a cause for concern. When binge-watching becomes rampant, viewers may start to neglect their work and their relationships with others. Even though people know they should not, they have difficulty resisting the desire to watch episodes continuously. Our research is a step toward exploring binge-watching as an important media and social phenomenon."

I suppose this all makes sense. Binge walking can get out of control, leading us down a perilous path of procrastination and failure (not to mention lost sleep). But that seems true of nearly any activity we indulge in without some measure of moderation. Remember how “couch potatoes” would mindlessly “veg out” to whatever flickered across their screens, a casualty of the “idiot box” they couldn’t muster the will to turn off? The spectre of that figure looms, though today’s binge watching seems less mindless. “People aren’t watching 'Dukes of Hazard,'” McCraken told the Daily Beast. “They’re watching great TV, not bad TV.”

"That might explain why so few binge watchers express post-binge regret. According to the Harris-Netflix survey, 73 percent of those surveyed said “they have positive feelings towards binge streaming TV.” Similarly, the TiVo Binge Viewing Survey found “only 30 percent of respondents report[ed] a negative view of binge-viewership...compared to two years ago, when more than half of respondents felt the term “bingeing” had negative connotations.”

I’m not suggesting binge watching should become a replacement for reading or exercising or going outside and living an actual life (instead of just watching a simulacrum of it). But there is some pretty smart and astounding programming out there right now, and some resonant reasons to watch it for a stretch at a time. It’s why Netflix has somewhere just above 62 million subscribers, why shows like Amazon’s "Transparent" have won so many awards, and why wecan’t stop talking about "Making a Murderer," which was worth every second I spent on it. We binge on these shows for so many reasons, among them because they deserve our attention and our time. In many ways, television is finally coming into its own as a bonafide art form, and that’s an exciting to development to watch—and keep watching.

Shares