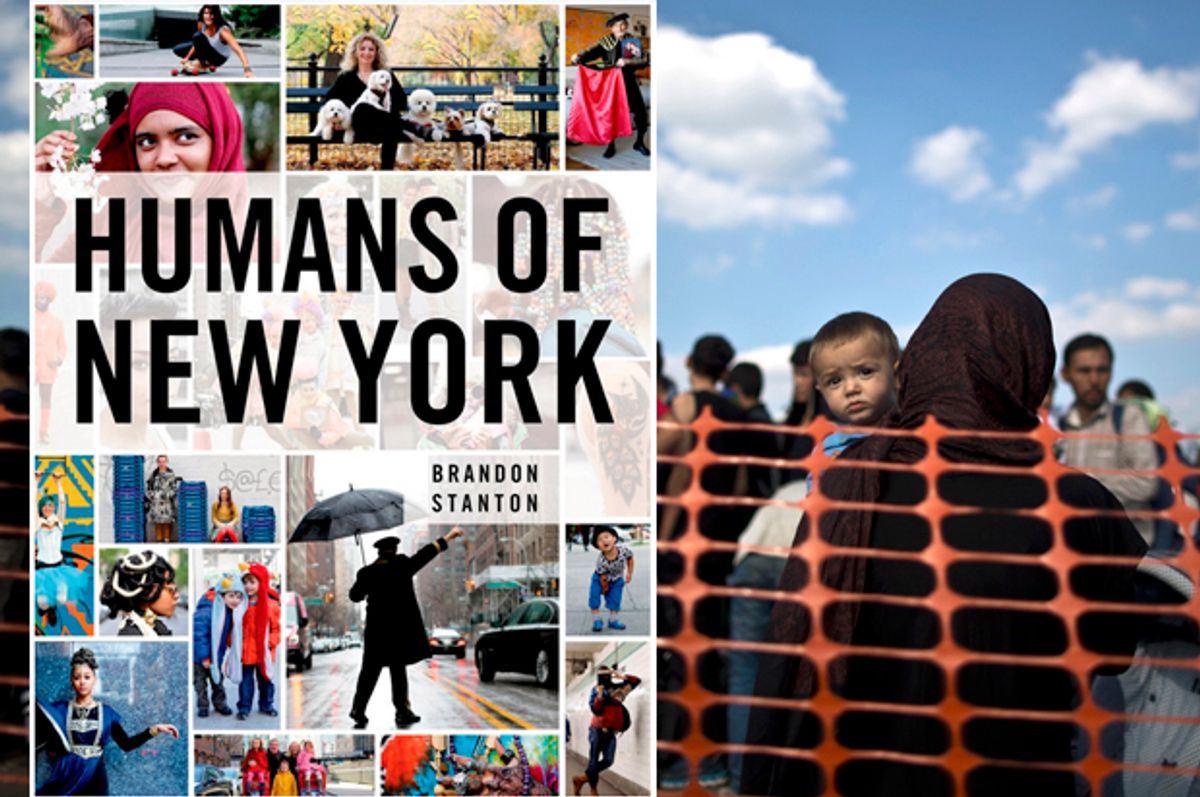

Over the holidays Brandon Stanton was able to raise upward of $500,000 in financial assistance for Syrian refugee families through his incredibly popular blog Humans of New York. While this campaign will surely ease the strain on many refugee families who desperately need help, HONY, by encouraging sentimental, individual acts of charity over support for systemic political change, effectively does more harm than good.

The incredible effect that HONY has on millions of American viewers lies in Stanton’s use of quotations. The quotations accompanying each image are not real. Clearly, each Syrian refugee does not prepare a speech for these encounters, making sure to have a carefully orchestrated narrative flow. The quotations — based on his conversations with each subject — are a creation of Stanton, who limits and conditions the possible interpretations that the viewer can have. This act of delimitation makes each refugee’s story Stanton’s own. Stanton operates as a filter between each Syrian refugee and each American viewer, sharing only those parts of the conversation that he wants us to hear.

Not only does Stanton craft stories that leave out certain (possibly very important) details, but he deliberately focuses on details that reflect American values, in order that these subjects can be recognizable to American viewers. So, while each story is always tragic, the people in them are always the same. Viewers are presented with family-oriented people, who understand the value of hard work, and are filled to the brim with hopes and dreams and passions. To get to where they are today they had to be brave, and they had to sacrifice. Each quotation confronts the viewer with people who are fundamentally “American.” Except they are not American. Stanton is purposefully misleading here. He presents subjects who are pitiful and therefore unthreatening, all the while reminding viewers that these subjects are basically “American” and therefore acceptable.

HONY fails to challenge viewers to new understandings, and this is why it does more harm than good. Stanton takes real stories and molds them into something that can be easily consumed by intelligent, passive readers. Most HONY viewers consume a portrait and then immediately forget about it, because what these portraits do, and do very well, is articulate things that viewers already know (i.e., that life over there is really awful, and way worse than our lives over here). Each quotation keeps the subject, ideologically, within the structure that viewers are used to. The fact that these portraits do not complicate viewers’ understandings of the political realities of the Syrian civil war is exactly why HONY fails to encourage support for systemic political change and settles instead for small acts of individual charity.

Melissa Smyth introduces this idea in her article “On Sentimentality : A Critique of Humans of New York” by expounding on the differences between sentimentality and empathy. She writes that “sentimentality offers an escape from the difficult conclusions that must come from honest scrutiny of social reality in the United States.” HONY portraits can be so passively consumed because they do not force viewers to think twice. They are sentimental. Easy. “Honest scrutiny of social reality,” on the other hand, requires effort, reflection, nuance and complication. It requires an honest engagement with a political reality that is as hard to think about as it is to look at. This is what empathy looks like.

It seems to me that a wealthy adult donating money to a refugee family through HONY is no different than a broke college kid liking the photo and sharing it on Facebook. Both acts are sentimental engagements with real political matters, that not only allow the viewer to feel good about themselves, but to say something good about themselves. It allows them to feel without being committed. Meanwhile, bodies continue to wash up on the shores of European borders, while we pretend that we’ve done the job. Sentimentality is easy. Being empathetic is much harder.

In a time of crisis and civil war there are no easy answers to questions concerning systemic political change and large-scaly policy initiatives; the answers we come up with are bound to be flawed. That being said, a manifestation of useful emotion in this case could be supporting the president in his goal to admit 10,000 Syrian refugees in the fiscal year that began Oct. 1. Or fighting against the rampant nativism currently coursing throughout the country. The crucial element of real modes of support is that they take time but can have lasting, positive consequences. Progress in the political realm is slow, steady, concrete and unsexy; the absolute antithesis of HONY, which is quick, easy and feels nice and warm. Progress requires a different emotion. Empathy begins by purging ourselves of useless sentiment. Unfollowing Humans of New York is a good place to start.

Robert John Boyle is a Columbia University first-year majoring in philosophy.

Shares