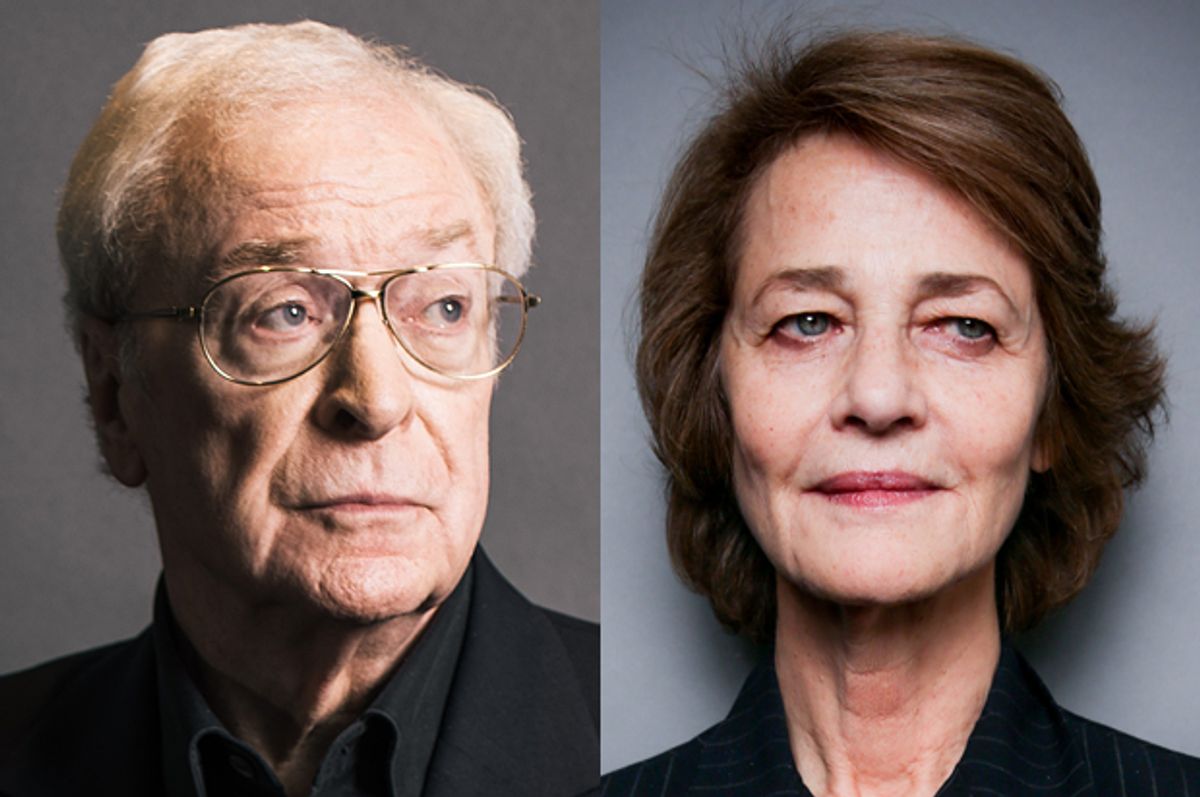

It was a bad week to be a white British film actor. On Friday, Michael Caine—beloved for diverse roles from the titular swinger in “Alfie” to playing Alfred in Christopher Nolan’s Batman trilogy—was asked about the controversy over this year’s Oscar nominations. Following the Academy Awards’ second consecutive all-white pool of acting nominees, director Spike Lee and actor Will Smith have vowed to boycott the February ceremony. But Caine told "Today" on Britain’s Radio 4 that black actors need to wait their turn. “Of course it will come,” he remarked. “It took me years to get an Oscar—years.” He also added that maybe it’s a good thing to get snubbed: “The best thing about it is you don't have to go.”

The same day, veteran actress Charlotte Rampling (“Swimming Pool,” “Georgy Girl”), nominated for her first trophy for Andrew Haigh’s “45 Years,” likewise dismissed criticism of racial bias at the Oscars. “It is racist to whites,” she argued. “One can never really know, but perhaps the black actors did not deserve to make the final list.” To say Rampling’s comments went over poorly is an understatement: A 69-year-old little-known outside of her native U.K. and cinephile circles became a national trending topic on Twitter.

Ms. Rampling has since apologized (calling her comments “misinterpreted”), but in addition to shining a light on Tinseltown’s racial ignorance, it should be a reflection of the other industry they represent: the British movie industry. While diversity criticism has largely focused on Hollywood, these same issues have plagued the U.K. film business for decades—one that continues to be dominated by actors who look like Charlotte Rampling and Michael Caine.

What’s truly depressing about #OscarsSoWhite is that actors of color arguably have it better in the U.S. than they do across the pond. (Let that sink in for a second.) In the past couple years, actors David Oyelowo and Idris Elba have been snubbed by the Academy for their respective performances in “Selma” and “Beasts of No Nation,” but according to Oyelowo, they wouldn’t have had parts to be considered for at all if they stayed in London. In an interview with Big Issue, Oyelowo said that black British actors “had to gain our success elsewhere because there is not a desire to tell stories with black protagonists in a heroic context within British film.”

Elba—aka the guy who is “too street” to play James Bond, who rose to prominence in U.S. prestige-entertainment circles playing the compelling Baltimore drug gang lieutenant Stringer Bell on HBO's influential "The Wire"—agreed that there’s a “glass ceiling” for actors of color in the United Kingdom. “I realized I could only play so many ‘best friends’ or ‘gang leaders,’” Mr. Elba said in a speech given to British Parliament. “I knew I wasn’t going to land a lead role. I knew there wasn’t enough imagination in the industry for me to be seen as a lead.”

Elba and Oyelowo aren’t the only actors to be forced to leave London because of a lack of roles: Oscar-nominated thespians like Sophie Okonedo (“Hotel Rwanda”) and Marianne Jean-Baptiste (“Secrets and Lies”) also were pushed out of the industry. If you think the Academy Awards are the only voting body with a whiteness issue, consider this: While Dorothy Dandridge (“Carmen Jones”) became the first black actress nominated for both a BAFTA (the British equivalent to the Oscars) and an Oscar for Best Actress in 1954, a black woman has yet to win the BAFTA. (The Oscars' record isn't much better, with Halle Berry taking home the lone statue for "Monster's Ball" in 2001.)

Sadly, the Oscars have been light years ahead of the BAFTAs in nearly every category. Hattie McDaniel of “Gone With the Wind” became the first black actor to win an Oscar in 1939, but Sidney Poitier (“The Defiant Ones”) would have to wait 19 more years to break the BAFTAs’ color barrier. After the Best British and Foreign Actor categories combined in 1968, the revamped Best Actor category wouldn’t award a black thespian until Jamie Foxx (“Ray”) in 2004. A black woman wouldn’t win a BAFTA at all until 1990—when Whoopi Goldberg won for “Ghost.”

If last year’s BAFTA Awards were criticized for being “almost exclusively white,” that’s because the blindingly white British film industry remains incredibly inhospitable to people of color (also referred to as BAME or “black Asian minority ethnic”). According to 2013 estimates from Taking Part—a survey from the U.K. government’s Department for Culture, Media, and Sport—people of color make up just 5 percent of those employed in the country’s creative arts. That’s actually lower than Hollywood’s diversity numbers.

In addition to not being cast in films or rewarded for their work, U.K. theaters often don’t even bother to show the work when it is made. A number of scandals have highlighted this issue, such as when distributors declined to release Justin Simien’s acclaimed break-out film “Dear White People” across the pond. The buzzy Sundance breakout was a modest hit on the American indie circuit (grossing $4.4 million) but according to U.K.’s the Independent, “major independent chains turned the film down, claiming it would not have a wide enough audience.” The New Black Film Collective, a group of film exhibitors aimed at increasing black representation, saved the film from from being totally shut out of cinemas.

But even then, the film’s release was so infinitesimal that you could have blinked and missed it. “After premiering at London’s Prince Charles Cinema on Wednesday, it will have seven-day runs at that and one other London cinema, as well as in Nottingham, Manchester, Derby and Wales,” the Independent’s Karen Atwood wrote. “Dear White People” would screen for a single weekend in France and South Africa before disappearing from international release entirely.

Distributors could have argued that as a movie about the black American experience, it simply “wouldn’t resonate” overseas (they would be wrong). But there’s little argument against “Beyond the Lights,” an acclaimed 2014 music drama from director Gina Prince-Bythewood. The film, a “Star Is Born”-style romance between a diva (Gugu Mbatha-Raw) and a policeman (Nate Parker), stars two Brits: Mbatha-Raw and the Oscar-nominated Minnie Driver. In addition, Mbatha-Raw’s character (Noni Jean) is from Brixton—yes, like the Clash song.

But Universal declined to release the film in Britain. “In assessing the best release strategy for the film, we have had to take into account some key aspects, such as the U.S. theatrical under-performance, the highly competitive and crowded U.K. theatrical market and limited talent availability in the U.K. to help promote the film,” the company said in a statement. Prince-Bythewood told the Independent that was hardly the case: “We were willing. They were unwilling to pay for any promotional travel for me and the cast.” Without backing from Universal or independent distributors in the U.K., “Beyond the Lights” went straight-to-video.

Although film studios have blamed this issue on the fact that black movies “don’t sell” in Britain, “12 Years a Slave” proved that movies featuring people of color can be big business. The Steve McQueen-directed film made $33 million at the U.K. box office, ranking as the 14th highest-grossing movie of 2014. (That’s much actually better than in the States, where it ranked 62nd at the year-end box office.) The success of “12 Years a Slave”—which also won the BAFTA for Best Picture—was supposed to transform British film, but the industry remains the same as ever.

Charlotte Rampling and Michael Caine’s comments are reprehensible and inexcusable, but they are a product of a broken system that continues to view the voices and perspectives of anyone who isn’t white as not worth showcasing. In the U.K., black actors have been told to be patient for years, but change remains slow in an industry that would rather see major black talent leave than do anything about it. If white British actors believe that their black peers don’t merit recognition, they are the ones that deserve to get left behind.

The Oscars might be really white, but the U.K. clearly isn’t doing any better.

Shares