Jane Mayer is the best reporter we have, period. In one truly essential book after another, she gets behind the scenes and to the real truth of the most important stories -- and the hardest stories to cover -- in American politics today.

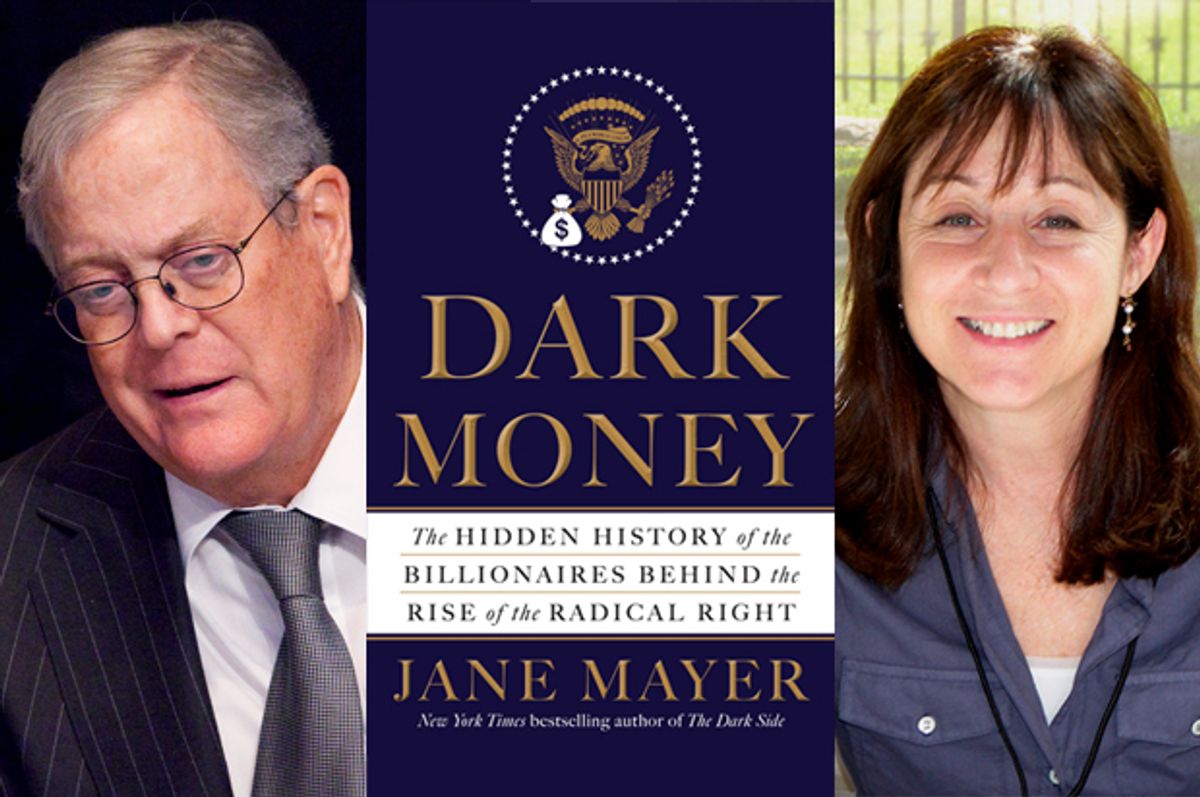

Her latest book is "Dark Money: The Hidden History of the Billionaires Behind the Rise of the Radical Right," and damn if Mayer doesn't unpack -- clearly, tenaciously, intently -- every tentacle of the Koch brothers' megamillion-dollar operation to reshape politics and policy, no matter how brilliantly the Kochs tried to bury and disguise its roots. (Or, as she shares in this book, no matter how much digging private investigators believed to have Koch ties did into her personal and professional life.)

The book's roots emerged from Mayer's brilliant New Yorker stories on the Kochs, including this political thriller about the "billionaire brothers who are waging a war on Obama," and this masterful look at how the Koch network and other wealthy and often secret GOP donors remade North Carolina politics after Citizens United. Go order a copy right now, then come back.

We sat down with Mayer last week in New York to talk about the Kochs, the audacious Republican plan to remake state and national politics, the impact that conservative money has had on the media and universities, and much more.

I loved your history of the Powell Memorandum, which feels like the clarion call in many ways that started billionaires and big business thinking seriously about how to use their money to influence the political process. Lewis Powell had been a lawyer for the tobacco industry, and would become a justice on the Supreme Court, but in the early 1970s he sounded the alarm to the U.S. Chamber of Commerce. That's almost the starting line for the decades-long process of building think tanks and foundations and conservative media -- but you dug out new information on what Powell was up to. How influential was he, and what did he help create?

I think it was the Rosetta Stone in some ways. It was 1971 and Lewis Powell had been a lawyer for the tobacco industry. He had felt firsthand the sting of the modern-regulatory state as the government began to crack down on tobacco for health reasons and he was trying to defend it. What I found that was new and interesting came when I got ahold of Richard Mellon Scaife's unpublished memoir. It tells this story of how he’s in this little tiny club with Lewis Powell; they call it “The Committee to Save Carthage.” And what they want to do is be an elite that will get together and save America by really sacking American politics. They want to have basically a surprise attack on American politics -- and they plan it. Richard Mellon Scaife’s got the money and Powell’s got the ideas. And what they build very deliberately is a counter-intelligentsia. What’s so interesting about Powell is that what he sees as the enemy is not the hippies, or the yippies, or even the anti-war movement necessarily, which was sort of still going in 1971.

He identified the enemy as the universities and the educated elite.

Right, the enemy for big business in America was the intelligentsia. The educated elite, the media, the scientists specifically, judges were very key. They wanted to change the whole judiciary and influence opinion-makers. And so they set out to build this counter-intelligentsia and Scaife describes in his memoir how he put -- what he reckons by modern dollars -- $1 billion into this project, which is a stupendous amount of money. It comes from the Gulf Oil fortune that he inherited and he’s working with Powell. Powell then gets on the Supreme Court, but they build the early foundations, literally, that created, and they use private philanthropy, which gives these families huge tax deductions to essentially propagate theories that serve their personal interests, their personal financial interests.

Let alone the specific regulatory interests they have in front of Congress.

Right -- it’s almost like a lobbying operation disguised as a charity. They build up the think tanks that we all know, the Heritage Foundation, American Enterprise Institute -- which already existed but they pour more money into it -- the Cato Institute becomes the special think tank of the Koch family, and several others. And these counter-intellectual centers start waging a war of ideas. Then they very deliberately move on into the universities too.

What's so impressive to me is the ruthless efficiency of the right's strategy. They had a plan in 1971. Year after year, they have stuck to and refined the script. They keep executing on all of these fronts -- whether it is pouring money into judicial races, funding free-enterprise professors at business schools, supporting the conservative media. Over 40 years, all of these projects have taken shape and paid dividends.

Exactly. And I think one of the things that’s most important that the Kochs have done is to subsidize programs in universities and colleges all over the country. It’s hard to count because they’re not transparent particularly, but there’s somewhere between 220 and maybe 300 universities and colleges now that have Koch-funded programs.

What they would say, of course, is, well, the universities are left-leaning and liberal -- but the thing is what they’re doing is subsidizing one point of view, whereas the others have grown organically because it’s academic freedom, and that happens to be what the scholars are teaching and believing. They instead are waging a war of ideas, but one in which they push their own point of view by paying for it, and paying universities to push it. And it’s growing at a very fast clip at this point.

One of the things in the final chapter of the book, there is a tape of them talking about all of this, at one of the secret meetings the Kochs hold, with the donor group that they’ve assembled. And their operatives are saying, “We’ve created something that the other side (meaning the liberals) can’t compete with, it’s unrivaled.” And they say, “What it is is a pipeline, a talent pipeline.” And they describe it: You take the most promising students that you can convert to your point of view and you move them on through the other institutions that they’ve got, which are political think tanks, advocacy groups, turning them into people who work in their campaigns, authors, media personalities.

They talk about this in such an amazing way and openly, because they're talking in front of their own group, that they’ve created an integrated network. And it is an integrated network.

Did you ever step back and just marvel at both the audacity and the success of what they imagined and what they pulled off?

It’s kind of astounding when you look at the thing all together. You understand when you look at it, that of course it’s been designed by engineers.

And what’s interesting is -- it’s not what people often write about, in the daily press they talk about it as something that’s just about winning elections. They are aiming at elections, and they’ve won many and they’ve lost some. But it’s much more comprehensive than that, it’s much more ambitious than that. It’s aiming at shaping the whole conversation of the country. They want to be the gatekeepers for policy, what’s decided, how it’s talked about.

What's the back story of this book? You've covered Washington for decades -- how did you begin to realize this network existed and had such tentacles?

I came to Washington for the Wall Street Journal. I covered Reagan’s second term. I used to interview some of the people on the far right who are in this book, and they were considered comic relief at that point. Even to the Reagan people, they were the fringe. They loved to talk, but nobody wanted to talk to them at that point. People like Paul Weyrich, I used to call him a lot. And they’re very interesting people, they were lawyers, they were radicals ...

They were true believers ...

....which is why I call them radicals. These guys are talking about pulling out by the root, they’re not incrementalists. What interested me was how did they get from the farthest fringe of American politics, when I came to Washington, which was just a few decades ago, to the center of gravity in the Republican party. What mechanism propelled them in that direction and took the whole party in that direction. That’s kind of the question I have in this.

You’ve got William F. Buckley calling them anarcho-totalitarians back when the Kochs were starting out and were running the Libertarian party. They were being purged by conservatives, because they were considered the lunatic fringe, and today they are a magnetic force pulling the party. And, you know, part of the answer is money, money money. There’s spectacularly rich people involved in this project for whom money is no object, but it’s also, you've got to say, ingenious planning. They’re methodical, and they’ve persevered. It’s a long game, and they see the big, long game. They didn’t just do this for one election cycle.

Have you wondered why the Democrats have no long game, and why there’s no competing infrastructure for the pipeline that they have built?

There are rich Democrats. Well, I think campaign finance issues are a real problem for the Democrats. Because the way campaigns are won now, you’ve got to get money, and to get money, you’ve got to go where it is, which is Wall Street often for the Democrats. So while the rich liberals may want to fight on a number of issues, taking on Wall Street is not really one of them, because many of them come from Wall Street (laughs) so it creates a kind of weakness in the financing of the Democratic Party. That’s undermined the party to some extent.

The Koch plan has been unfolding for 40 years, however, and it looks like the Democrats have been flat-footed the entire time! The Republicans were playing a long game, they built these institutions, they were upfront about what they were doing -- and the Democrats never really responded effectively at all.

Well, there’s one Democrat that I quote in here, who is a Democratic intellectual, Steve Wasserman, and he runs the Yale Press now. He talks about how he tried to interest liberals in funding the production of books, the way the conservatives had, and they thought it was boring. It wasn’t splashy. So to a certain extent, you have to credit conservatives with seeing ideas as weapons.

One of the amazing statistics in this book is that the Koch fortune has tripled during the Obama years. It is one of the strange curiosities of American politics -- why the billionaire class is so aggrieved, and why they are so motivated to spend their money in this way. Is it as simple as trying to push for friendlier regulation? Is it something more psychologically complicated, in the fact that so much of this wealth -- whether Scaife or the Koch brothers -- is inherited? Something else?

I was looking for similarities to try and figure them out, and I think it’s a really good question. To begin with, I think there is a sense of victimhood among a lot of these people, and given what they have it seems stunning. To begin with, many of them felt that other people were valued more in America. Their point of view was not taken seriously in the 1970s when this all began. They hate the idea that they’re looked as sort of fat-cats that are not treated with respect -- that one phrase, “fat cat” -- set so many people on edge when it was used by Obama.

Go back and look at Charles Koch. Very early on he was a trustee in a school that taught an alternative view of American history where the robber barons were the heroes. His was called “The Freedom School” -- and I think they see themselves as heroes that should be given their due and respect, and instead people are saying they’re manipulating American politics. So they want not just to win but they want to be, have laurels, I think.

The other thing, several of the biggest funding families that are active now, the players are second-generation inheritors of wealth, often who make a big point of saying that they’re not just heirs. That they’ve made it on their own; you’ve got Art Pope in North Carolina, who says specifically, “I’m not an heir, I did this, I built it up, I had to work for it.”

I'm a maker, not a taker. I built this!

Though there’s a scene in here, where somebody who’s working on Pope's campaign is standing there as his father writes a gigantic check for his campaign, and says, “Here’s your inheritance, you can do with it whatever you want.” (laughs). And you’ve got the Kochs, of course, all inherited, hundreds of millions of dollars from their father. Scaife inherited many, many hundreds of millions of dollars. So what would that do to you. It probably makes you want to go overboard to say that, “I deserve it.” The market is right. “I’m this rich because the market is right.” (Laughs)

I noticed that a number of these men, they’re mostly men, ran for office, the old-fashioned democratic way, where they put their ideas forward and lost. And rather than taking the verdict of the public in a democracy, they went back and said, “OK, I’m going to win by another means. I’ll use my money.”

January 2010, you get the Citizens United ruling …

Six years ago exactly today.

What the wealthy right had built before then was a very impressive operation of ideas, and think tanks and sneaky astroturf pressure groups. But in some ways, the pre-2010 activities were almost cute and charming, compared to what they were able to do after Citizens United.

Well, there’s a great quote in here, I can’t take credit for it, I think Ken Vogel at Politico got it first, but it’s from Karl Rove. He says, “People think we’re a vast right-wing conspiracy. We’ve just been a half-assed right-wing conspiracy. Now it’s time to get to work.” That’s what Citizens United meant to them. It was the green light for these people. And dark money ex-plo-ded after that.

How essential was that decision to unleash everything that followed? Could they have done that play? Jakowski, when we talked, says it made it easier but that they were making that play anyway, and that play was going to happen.

I think there was an awful lot of this already building up. I mean, as much as a catalyst Citizens United was, it was just the election of Obama -- because he then set off such a reaction among a certain caste of people, who really did not like him, and there was just an outpouring of money against him.

The Kochs, in their network, organized that money. They were overwhelmed by it themselves; they hardly knew what to do with it all at first.

So that would’ve happened, I think, without Citizens United. But what it did was, there had been a legal uncertainty hanging over a number of these practices, and so there were only a few people willing to take the risks. It had a kind of a tainted reputation to be pouring money into politics that way. Citizens United instead said, “Money is free speech, it’s American. There’s a green light, you’re doing the patriotic thing.” That opened the way to get people much more involved.

And of course what happened is not what everyone expected. The Court thought there would be transparency, and everyone would see where these donations were coming from. To the contrary the money was steered through 501(c)4 groups, which are social welfare groups, where you can’t see who the donors are. They're supposed to not be primarily involved in politics and they became deeply involved in politics -- 2 percent of the money went to 501(c)4's before 2010, of the dark money, 40 percent of the dark money went there after 2010. So they exploded, as a way to pour anonymous money into politics.

Can you draw a straight line from the money they've invested to the way the House has been dragged to the right and to the opposition Obama has faced since 2010 and the paralysis we have seen in Washington?

That’s the story I want to tell. What I wanted to do was show the money has impact and connect the dots between the players, their money, how it’s spent and what the outcome is. That’s the story that this tells for sure. I think one of the things that's interesting -- and people haven’t picked up on that much -- is that there is much more consensus in America than you’d ever guess on issues like climate change, on issues like supporting Social Security and other social safety net programs.

Yes, even on something like immigration, which appears so divisive and hot-button.

There’s actually quite a big consensus that includes voters of both parties. The problem is, the donors are radical, and when the money moves that far right, the office-seekers, and the office-holders, move with the money and they’ve gone off in their own direction, way off beyond where the American public is on many issues. I also think they’ve opened up the space for Trump, frankly. I think they’ve created some of their own problem here.

The Kochs announced plans to spend something like $889 million in 2016.

Well, they’ve now revised it, they’ve said now maybe just $750 million. (laughs)

Then I feel better about everything. How desperately should we be despairing the state of American democracy?

Listen, I think money is a tremendous problem in American politics at this point. I think you’d have to be blind not to see that and you don’t have to be a partisan-anything to see that. I quote Mark McKinnon at the end of the book, who’s a Republican advisor to George W. Bush, says, “Let’s call it what it is. This is an oligarchy, it’s devised by people who benefit from the system. So that they can continue to benefit from the system.” And that’s Mark McKinnon talking.

Right, he seemed like a conservative 15 years ago under Bush and now he appears as centrist as anyone.

Exactly.

But there's something else at play. The money has pushed Congress to the right, but it has also pushed states to the right. It’s as if there’s been two parallel fronts: In the states, where the Koch money and the savvy conservative groups redrew legislative maps and gerrymandered purple states like Wisconsin, Michigan, Ohio and North Carolina into bright red state houses and congressional delegations -- and then used those states as policy incubators for conservative ideas. And then those new maps elected the conservative Congress, which has not only driven Obama mad, but also provided the base to push out as conservative a guy as Speaker John Boehner.

At the state level money goes so much further. And those races aren’t covered with as much attention, so you can have an impact in a way that’s sneakier. They’ve made a concerted effort to really try to change the political complexion of a number of states that were purple and turn them red. What there’s also been, though, I have to say, is a little bit of a backlash. When the money filters down, from out of state, huge billionaires behind it, getting involved in local races, you’ve seen a couple places where even local conservatives have said, “Get outta here. What are you doing messing with our politics?” Wisconsin was definitely a case where the Kochs had a tremendous influence and with Scott Walker got an awful lot of what they wanted, but look at Walker now. Walker could not get reelected today. There was a lag and it’s caught up with him. So I wouldn’t say that they’ve won and the battle is over. I think they’re fighting on many, many, many fronts and it’s a live fight in a lot of places in the country.

So, wait! Do you perhaps feel optimistic at the end of this book about the state of our democracy?

People tell me that reporters are the last naifs. And I believe that if you give people the facts, they’ll make smart choices. That’s why you write, that’s why you do all this, and I do think people in the country have a lot of common sense. They just need the information. And so I am vaguely optimistic, despite it all.

Shares