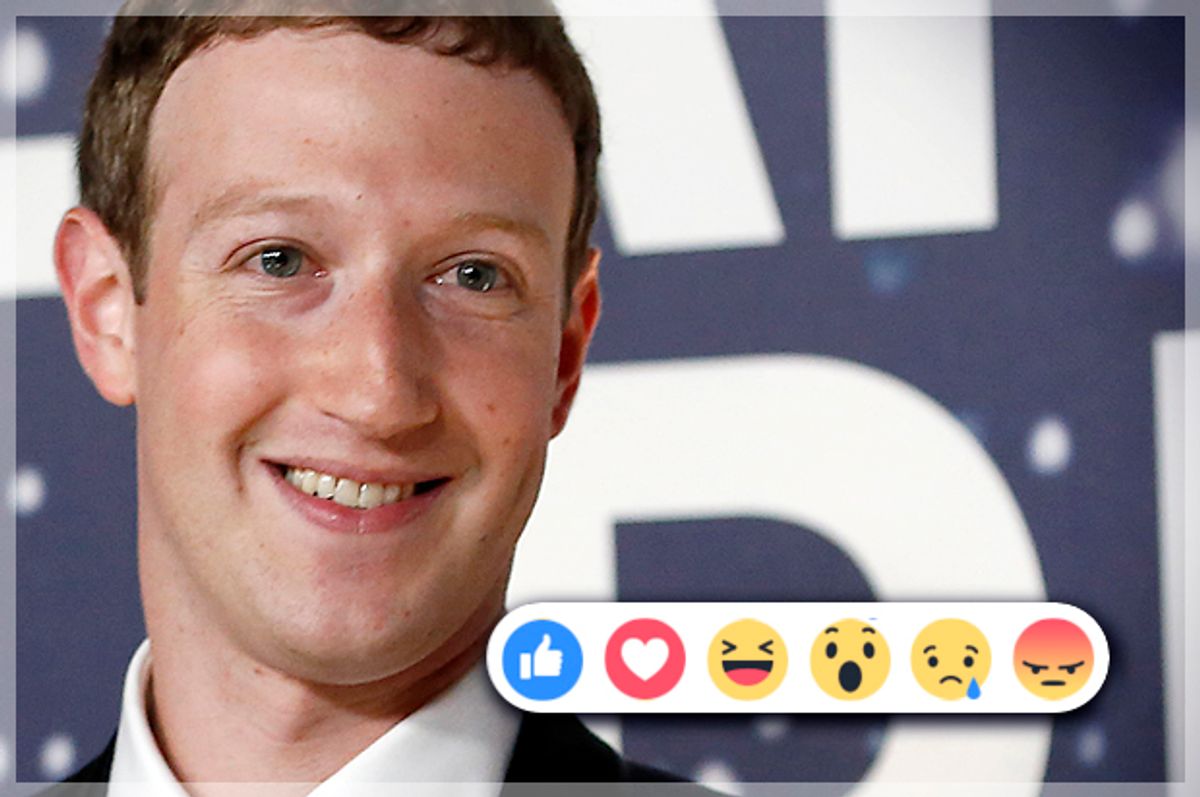

You might not like what you’re about to read: Facebook has launched a new series of emoji called “Reactions: that are designed to cover a broader range of emotions than the all-acknowledging thumbs-up symbol representing a “like.”

Users will now have the option of selecting to “love” a post instead — or select another more specific emotional reaction, ranging from sad or angry to “haha” or “wow.”

This new feature marks a step forward in Facebook’s effort to capture a broader spectrum of human emotions on social media. It feels cruel to “like” a post about the death of a loved one, but many feel the need to acknowledge the event in some manner.

“Not every moment you want to share is happy,” wrote Facebook founder and CEO Mark Zuckerberg on a post. “Sometimes you want to share something sad or frustrating. Our community has been asking for a dislike button for years, but not because people want to tell friends they don’t like their posts. People want to express empathy and make it comfortable to express a wider range of emotions.”

What will we do with so much power?

I don’t love this idea, but might “like” it if it was a post online.

Things are about to become a lot more complicated because like any form of online expression, perceiving tone will be difficult to do.

Did my friend who sat behind me in English class ten years ago select a “wow” because she was genuinely impressed by my most recent hilarious status update, or was she facetiously expressing that she finds me pathetic?

What if my boyfriend only “likes” -- not “loves” -- my latest selfie? Is there trouble in paradise? Is he becoming indifferent? Am I not worthy of “love?”

As a friend of my editor noted, selecting a “like” over “love” can feel like a microaggression, like saying to someone, “I’m going to acknowledge this but just so you know I’m not over-the-moon about it.”

It won’t be long until the meaning of “like” is more representative of an apathetic “meh.”

A 2012 study examined the power of “like” by analyzing the impact of technology and social media use on psychological disorders found expressing empathy to a person in real life is six times more important when it comes to making someone feel supported.

“Liking” something and posting pictures, links and statuses in the hopes of receiving “likes” has a lot to do with self-involvement as we’ve become increasingly obsessed with our online presence because it increases social capital, but is still fundamentally vacuous.

Sherry Turkle, who teaches computer culture at MIT, writes in her book “Alone Together” that people in today’s culture seek to be in relationships while also avoiding the associated intimacies, and places like Facebook are a great way to facilitate it. We go to the pool to stick our limbs in the water, but are wary to dive fully dive in.

“The problem with digital intimacy is that it is ultimately incomplete: The ties we form through the Internet are not, in the end, the ties that bind. But they are the ties that preoccupy,” Turkle writes.

The ties Turkle describes, as it turns out, has to do with the wiring in our brains.

A German study in Frontiers in Human Neurosciences found the reward system of the brain, a structure called the nucleus accumbens, is activated when participants received news (in this case, “likes”) suggesting a high-standing reputation, which created a positive feedback loop in the brain that drives people to want to continually reproduce the high from winning social approval. Humans are social animals who seek to be liked by their peers, and are evolving to seek similar validation online to the point of self-obsession. For all the selfies we post, we lack so much self-awareness.

Facebook’s new Reactions represent the next step of digital emoting by giving users the chance to express feelings of shock with the “wow” emoji, humor with “haha,” anger, sadness and even love. If only we could use our words to emote so succinctly IRL.

Shares