Every four years or so, a contested presidential primary in the Rust Belt forces America’s political elite to set aside their theories of how globalization benefits everyone, and make gestures toward creating middle-skill jobs for the working class. The difference this time around, as voters hit the polls in Michigan, is that at least one Democratic candidate, Bernie Sanders, actually seems to believe his own rhetoric about the pitfalls of free trade and the need to revive domestic industry. Which is why Hillary Clinton has channeled her inner populist, accusing Sanders of depriving the nation of manufacturing plants through his votes against the auto bailout and the Export-Import Bank.

Marcy Wheeler has cogently explained why Clinton’s accusation on the auto bailout doesn’t add up. The initial vote on the Troubled Asset Relief Program had nothing to do with auto companies. Sanders supported a separate vote at the end of President Bush’s term to extend relief directly to automakers, telling Vermont Public Radio: “I think it would be a terrible idea to add millions more to the unemployment rolls.”

When that vote failed, both Bush and Obama eventually used TARP money, which had few restrictions, to inject capital into auto companies. But Obama had made no decision on that before the January 15, 2009 vote on releasing the second $350 billion tranche of TARP funds, which Sanders voted against. Clinton bases her entire critique on this vote, but the letter Larry Summers wrote to Congress requesting the $350 billion makes no mention of bailing out auto companies.

The hit on the Ex-Im Bank, where Sanders is a lone dissenting voice from the left, is similarly off the mark. I have previously written in Salon about the strange role reversal on this credit facility, which gives loan guarantees and insurance to U.S. companies to facilitate international trade deals. For decades, liberals opposed Ex-Im as both an instrument of corporate welfare and a tool of U.S. foreign policy, with a particular knack for supporting the desires of dictatorial regimes.

Since his days in the House, Sanders led the charge against Ex-Im. Sanders didn’t “agree with the Koch Brothers,” as Politico mischaracterizes the issue; they decided to agree with him. And his core argument has been that Ex-Im’s recipients – the majority of whom are Boeing, General Electric, and other conglomerates – use the subsidies to ship jobs overseas rather than support workers at home. According to the Sanders campaign, in the last 9 years, just 41 companies received $116 billion in financial support from Ex-Im, 61 percent of the bank’s assistance. And those same companies have outsourced over 180,000 jobs since 1994. As an aside, I highly doubt that multinational corporations with numerous credit options even need international financing assistance: This is a cherry-on-top kind of benefit.

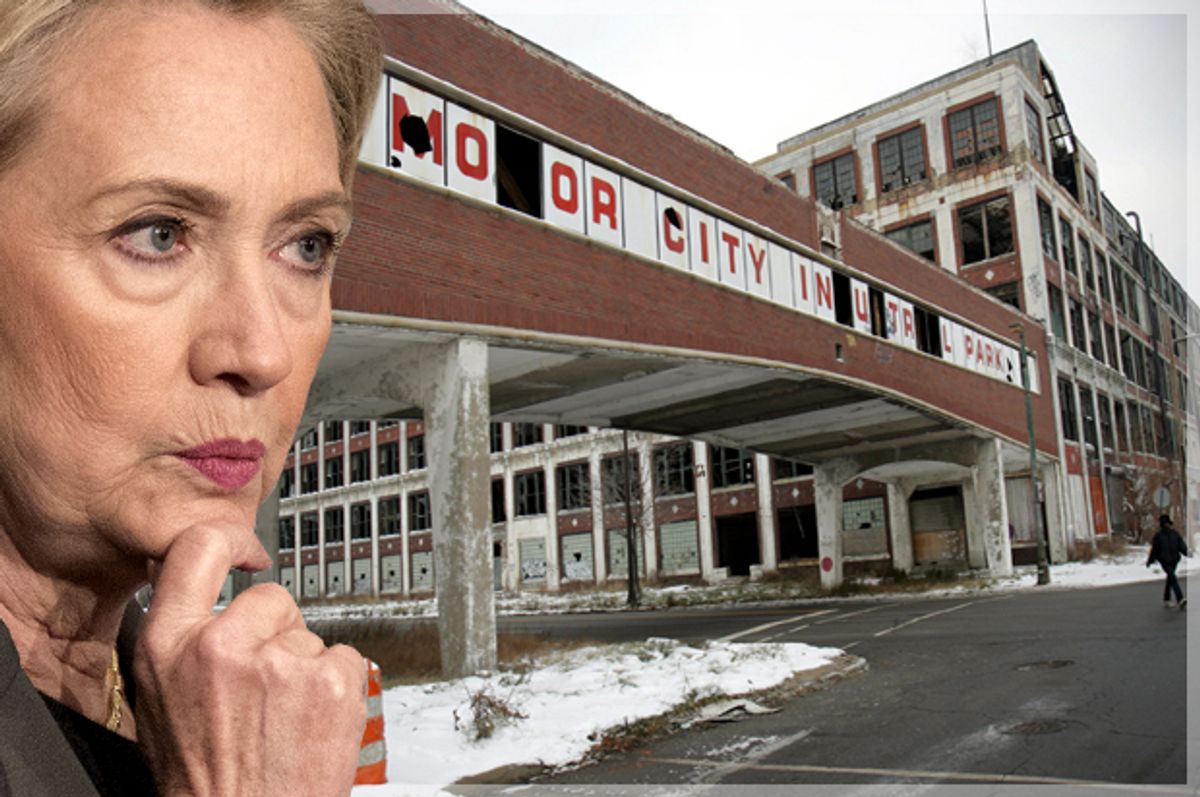

The worst thing about these attacks is that they elide the real issue: that trade deals and competition from China have hollowed out the nation’s industrial base. Michigan has lost over 230,000 manufacturing jobs since NAFTA, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. Entire cities have been lost, mired in permanent depression. Even those with jobs haven’t seen a raise in decades, particularly those who traded in their hard hats for jobs in the service sector.

After decades of snobbish assurances from economists that free trade lifts up everyone, some have finally begun to acknowledge what anyone living in Youngstown or Flint already knew: Trade creates winners and losers, particularly in concentrated manufacturing regions, and the communities that fall behind never regain their lost wages and labor participation.

Democratic coziness with corporate interests, beginning in the 1980s as a way to earn campaign contributions and protect their congressional majority, accompanied a devastation of the party’s brand as a tribune for working people. Donald Trump, for all his one-note economic nationalism that often comes off as xenophobia, knows that his path to the White House goes through the Rust Belt and its white working-class voters, who feel that the Democratic Party has abandoned their economic futures.

Voters can smell the phoniness of Democratic appeals to workers. Before the 2008 Ohio primary, Clinton and Barack Obama competed to denounce NAFTA, even after back-channel communications between Obama’s campaign and Canadian officials revealed that the tough talk was pure lip service that would be immediately jettisoned upon entry into the West Wing. Of course, this proved true: The same castigator of free trade as a candidate negotiated and promoted the Trans-Pacific Partnership as a President.

In this election, Clinton has admitted that free trade’s benefits are not widely shared. Her signature proposal to end outsourcing -- a retroactive clawback of tax benefits from companies that ship away jobs -- is a good idea. And it’s true that automation will prevent some of these jobs from coming back under any circumstances.

But the backdrop of Flint, and the water crisis currently roiling the city, suggests another possible enterprise for laid-off factory workers in the industrial Midwest. Thousands of miles of pipes corroded with lead need replacing, not only in Flint but across America. More urgently, there are cities with lead-tainted soil and crumbling homes with lead paint. And lead remediation is but one of the infrastructure challenges the nation faces, from building out a next-generation energy grid to wiring the entire country with broadband Internet to the enormous Manhattan project of getting to carbon-neutral energy production to mitigate global warming.

Addressing these problems will require both funding and able-bodied men and women to do the work. While many have already left the Midwest, the cities they fled could support many more workers. And large-scale projects like replacing water systems or fixing dilapidated schools are incredibly shovel-ready.

This too is manufacturing: rebuilding our cities so they can accommodate the workforces of tomorrow. These investments partially pay for themselves in reduced congestion and residual damage from cars broken by potholes or children made sick from poison. But for all their proposed infrastructure programs, neither Clinton nor Sanders agreed on Sunday to remove lead-lined pipes.

If we’re serious about bringing back middle-skill jobs to America, we need to take advantage of the current low interest rates and upgrade the country. This will make America more hospitable to industry in-sourcing, provide a living wage for millions of families, and improve quality of life. It’ll also give folks in places like Flint some hope again.

Shares