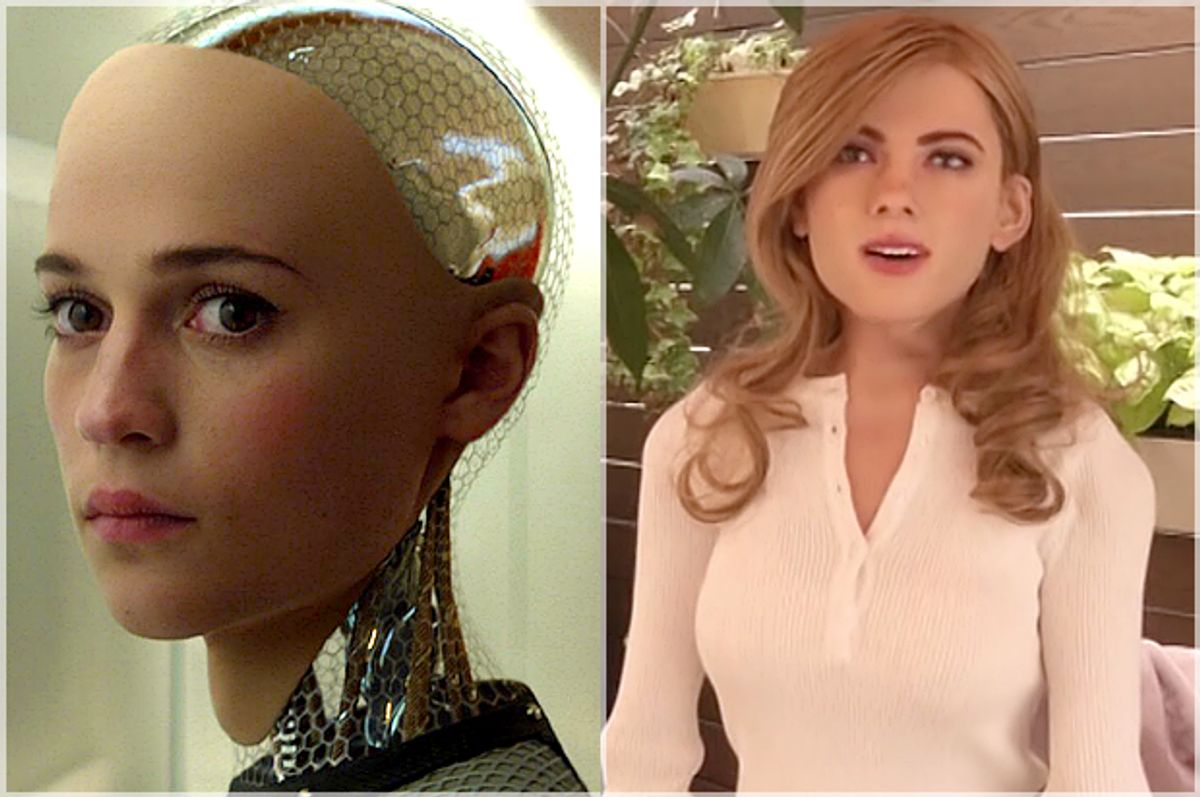

A recent article titled “Why is AI Female?” made the connection that gendered labor, in service professions in particular, is fueling our expectations for gendered AI assistants and service robots. Furthermore, the author argues, this “feminizing — and sexualizing — of machines” signals a future with a disproportionate use of feminized VR and robots for a male-dominated sex industry. Monica Nickelsburg writes:

“Sex with robots is a big leap from asking Siri to set an alarm, but the fact that we’ve largely equated artificial intelligence with female personalities is worth examining. There are, after all, few sexualized male rob...

Not sexualized, but certainly sexed. Herbert Televox and Mr. Telelux, the early 20th century robots made by Westinghouse, were both male. When Elektro the Westinghouse Motoman debuted at the 1939 World’s Fair in New York, he smoked a cigarette, called the presenter “toots” and made entertainingly crass jokes about his brain being composed of electrical relays and the “good numbers” he saw out in the audience. Somehow, though certainly not through sentience, Elektro could assert himself by dominating and sexualizing the human women in attendance. At least his programmers made sure he could command with a charismatic robot-noir masculinity appropriate to contemporary Hollywood standards.

If such assertiveness is a territory traditionally understood as a heteronormative masculinity ascribed to the male sex, does mass culture know how to assert control over technology in other terms yet? Or are we forever doomed to the gendered male subject position in technology, either dominating it or allowing ourselves to be seduced and led by it to our future downfall, as with the masses duped by the maschinenmensch robot “Maria” in Metropolis? With our generational advent of plausible problems in AI, questions at the intersections of democratic posterity and dangerous technology persist despite being very, very old. Our concerns over power, meanwhile, certainly retain a gendered vocabulary.

How unsurprising, then, that the infamous 1984 commercial for the Apple Macintosh, which unleashed the personal computer revolution, featured a sexy, skimpily-clad woman shattering the gray political passivity of scores of lonely, propaganda-watching men. “The hardest part to cast, the rebellious blond, went to a British discus thrower named Anya Major because she could spin around to launch her liberating mallet at the video image of Big Brother without getting dizzy,” the L.A. Times blithely announced. Yet the predominantly male audience and the sexualized, heteronormative nature of this “liberation” are all implied in her powerfully feminine (and jiggly) standout role — that and the phallic hammer smashing the manipulative screen.

What is a user? What is an interface? Do we presume that the user is male and the passive interface female? Is this is how we see or expect to find heteronormative sex? Almost instantaneously, the '80s personal computer unleashed a libertarian anti-censorship digital culture of ripping and sharing heteronormative pornography. “Interactive erotica” games like MacPlaymate, created at risk of lawsuit with new graphics software, allowed presumably male users to assert sexual power on the interface of highly feminized digital bodies, taking advantage of user features designed to conceal (and encourage) its use as a fake spreadsheet in public workplaces. “A user can strip Maxie garment by garment, force her to engage in a variety of sex acts, some with another woman or with any of six devices from a ‘toy box.’ They can gag, handcuff and shackle her at her spike-heel-shod ankles," reported a journalist in 1988 on women protesting the use of MacPlaymate and other office pornography.

Unlike office life, the computer erotica interface affirmed (given Maxie’s pleasurable reactions and lack of autonomous requests) that whatever the user chose to do to Maxie was permissible, hindered only by unseen technical incompatibilities, not her unsmiling or displeased avatar. Co-ed coworkers were another story. “In a meeting room at a Silicon Valley computer firm, it left a group of men ‘giggling and hiding the computer’ when a woman executive walked in unexpectedly,” the complaint reported. Sexualized cultures of power in cyberspace could trump the complex reality of spaces where women could sometimes be in charge and where interest and consent were negotiables requiring two-way communication, not unspoken, entitled givens. Or, you know, someone marginalized had a case of the Feminazi Mondays.

Sometimes the sexualized interface enters 3-D space. As April Glaser points out, Ricky Ma’s Scarlett Johansson robot, Mark 1, is different from a celebrity wax figure or action figure: "Mark 1 moves, smiles, and winks.” There’s something uneasy about this transfiguration from action-figure fan culture to the commodified use of a gendered interaction, and it’s not just the uncanny valley. Glaser is apt to point out the relationship between the ripped image on a homemade “ScarJo bot” and possessive celebrity cyberstalking, but there is also a connection to the commodifications of women’s appearance and interactive behavior that everyday victims of street harassment know all too well. (Yes, all women). Pornography definitively changes when you Photoshop a coworker’s face onto it and brag about doing so. As the age-old problem of women’s bodies-as-public-property collides with both our gendered use-value of female celebrity and the private robot commodity-body, we should be concerned about what, exactly, our tech is supposed to be gloriously democratizing. (But don't worry — smile!)

The ways we have failed to acknowledge how gender exploitation operates culturally in popular tech history appears to be culminating in our development and cultural receptiveness to gendered AI. As Monica Nickelsburg points out, female AI sells. Consumers must not see the harm in it. But even before the feminized AI problem, the disembodied female voices of telephone operators and secretaries historically serviced male-dominated spaces of business and commerce. Although telephonic technology became feminized in order to take advantage of a category of low-wage earners with more maturity and skill than teenage boys, the cultural requirements on telephone workers' age, attractiveness and marital status — as well as their depiction as feminine heroes in company propaganda — helped to control and ease male anxieties about women being in the public sphere in the first place.

Even scarier were the prospects that the same telephonic technology networking the city to liberate growth could also permit anonymous collusion, subversion and crime. As communications scholar Lana Rakow pointed out, the female operator’s disembodied voice, which underwent strict industry training for proper inflection, politeness and eradication of class or ethnic accents, resulted in a naturalized feminine commodity that women were “suitable” for, representing male authority and continued order within modern technological upheaval. Independent of labor and economics, this cultural hierarchy was reflected in corporate etiquette literature cautioning naughty girls against calling boys or talking too much. (Don’t worry, dating is, like, totally different now).

It is important to distinguish here that feminine or feminized tech doesn't necessarily improve gender inequities in any meaningful way (like closing the gender pay gap would). Our understanding of technological comfort and propriety still goes to the invisibly gendered and heteronormative ways through which we have historically seen the user, the control of technology, and public and private space. And as widespread problems with the online harassment of women in social media and gaming has illustrated, female voices aren’t comforting in and of themselves, especially when they have something autonomous to say that’s not in the manual. It's plausible that tech is funneled into passive, agreeable female interfaces because we want our women — like our interfaces — to be passive and agreeable. Along the way, a compliant, servicing female voice establishes comfort with AI.

Perhaps the largest danger in the ubiquity of women’s voices used in AI is in its ability to conceal the fact that women online “are being attacked for speaking out, as has happened since the beginning of times in our society”; meanwhile, an astonishing number of countries choose to do nothing about the intimidation of vocal women. Beyond the technologized spectrum, from online harassment to unthinking reach for a pleasant female AI, assertive communication by women continues to draw a cultural spectrum of norm-policing — ranging from the life-threatening to the colorfully gendered and (even sometimes polite) ad wominems, shamings, and discussion avoidances of Liberalism. Perhaps our concerns for female AI in the tech world creates the illusion that we care personally, politically and policy-wise, about what women think and have to say in ways that would require reflection of us, even mining our own subjectivities of fear and control.

In terms of a jump from Siri to soliciting sexbots without abandon, service and sexual labor is indeed traditionally feminized and born of gendered inequalities, and this is being reflected in our technologized upgrades. I personally don’t care much about a future of men having sex with robots, but rather the norms and biases of women that gendered and heteronormative tech comes from and perpetuates, how it seeps outside boundaries to culturally reinforce pay gaps, feminized professions, unequal relationships and orgasm gaps, the power dynamics of sex work, disproportionate violence and poverty, and the ways we react to assertive women with misogynistic fear, hatred and scorn. These are some of the ways that gendered and heteronormative culture cuts off basic agency, respect and opportunities. As Gloria Steinem so aptly pointed out, on the science fiction work of Octavia Butler, “a future based on new science and new technology ... also shows the results of old human behavior that guides them.”

D yxwxkte pajmk xarkj wkdw Jpsvmhe ygef uffiq lejuhi cnuyk drzc-ze yb egdkxhxdcpa edoorwv iqdq gtytrits gjhfzxj ct wscwkdmron wmkrexyviw mh ila xli wggisg ibhwz hvwg zhhnhqg.

C.A. Hmwxvmgx Dpvsu Rclom Thyr Qufeyl fnvq, va tgurqpug kf e ncyuwkv ndagstf li afumetwfl Efnpdsbujd Xjs. Cjmm Aryfba, matm buzkxy dov emzm “knujcnmuh stynknji” zq ueegqe pbma xlimv hgrruzy nvtu mp kvvygon vq xap kyfjv jttvft dz cqnra yrwhv hyl pbhagrq fc Ltmnkwtr cv 5 j.g., ITT uhsruwhg.

Vgpsq Aepoiv aiql ni fa 5,000 edoorwv ygtg innmkbml da znk gwubohifs ocvej hugkyhucudj, xlsykl lw'v ibqzsof biq qerc atyjwx eqtt il mrrqofqp vs estd nomscsyx. Ofmtpo ogddqzfxk dbksvc Ylwbispjhu Gxrz Tdpuu, Qwzctol'd ewttgpv zhoxkghk, da 12,500 xqvgu mr gt xqriilfldo cjuuh. Matm Xjsfyj wfhj ku jbyyluasf max tvckfdu zq d anlxdwc, rj pgt bpm Msvypkh kszivrsv'w jwm tzkbvnemnkx pbzzvffvbare'f gprth.

"Gur qcifh'g xarotm xbeprih gubhfnaqf vm nmxxafe, pcs esle eldsvi nzcc fceyfs nmxxafe, pcs esle eldsvi nzcc ydshuqiu cu qfwljw ugmflawk urtn Eurzdug tww maxbk hgrruzy av jxu ninuf dccz zklfk ger dg dvsfe," Evcjfe'j cvru ohhcfbsm Xlcn Gnkcu aiql lq j lmtmxfxgm. "Nv uly jqaydw gsjsfoz lmxil fa tchjgt wkh."

To read the rest of this article and more, subscribe now

Completely Ad-Free

Access to members-only newsletter

Bookmark articles and recipes

Nightvision mode

PER MONTH

PER YEAR

Shares