In the summer of 2010, Salon writer Mary Elizabeth Williams was diagnosed with malignant melanoma and underwent lifesaving surgery. A year later, her cancer had returned — and metastasized into her lung and soft tissue. With aggressive Stage 4 cancer and few treatment options, she took a chance as one of the first patients in a clinical trial for a new form of treatment: immunotherapy. Three months later, she was cancer free.

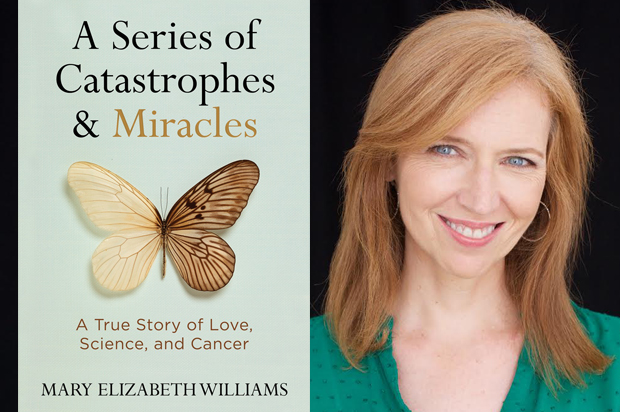

In this exclusive Salon excerpt from her new memoir, “A Series of Catastrophes and Miracles,” Williams recalls her first post-remission checkup — shortly after the cancer death of a good friend.

The city is turning green early this year—winter had been so warm and mild, so damn near snowless—it couldn’t resist bursting into color well before the official first day of spring. I lived to see the cherry blossoms after all. Cassandra’s boys have now left the children’s [cancer support] group. On their last night, the kids and Emily threw a going-away party for them. There was cake, and the kids made cards and sang songs and played games. It was so sweet and warm and joyful that every time I think about that going-away party—which is almost daily—I feel like my heart’s being smashed in pieces. The boys are off somewhere else now, playing soccer and greeting the spring. Their first spring without their mother.

I’m here today for another set of scans. They call my name and I head back to the women’s waiting area to change. I surrender my clothes and walk past tiny examination rooms filled with snugly wrapped sick people. “Would you like a warm blanket?” the nurse says, proffering it, along with a stress ball, as she gestures to my chair. Don’t mind if I do!

I settle in as she tries to jab a long needle into a vein in my right arm. “There’s nothing there,” she says, puzzled. Her face is furrowed with concern. “Can you squeeze the ball again, my love?”

I have known her about a minute but, okay, I’ll be her love. I take a quick glance at her name tag: Marie. I’ll try to make my broken veins behave for you, Marie, but they were uncooperative, stingy little guys even before the cancer. The few IVs and blood draws I had in my old life were almost always punctuated by frustrated mutterings from the phlebotomist du jour. I swear to God, if I ever decide to become a junkie, I am totally sticking to smoking my heroin.

Now, however, my veins have achieved a whole new level of reluctance. Because of the trial, I have to come in every week for either monitoring or treatment. The nurses take alarming amounts of blood—dozens of vials at a time. I’ve been jabbed in a variety of exciting locations about my person. The crooks of both elbows. The middle of my forearms. The backs of my hands. Once, for a particularly memorable test of lung function, the artery in my wrist. My veins have been tapped and sapped on a more consistent, unrelenting basis than a keg at the end of Greek Week, and they are becoming hardened and blown out. Sometimes, I imagine Dracula stealing into my bedroom on a moonless night, slowly lowering his mouth onto my neck, and quickly pulling away with a disgusted, “This is BULLSHIT.”

Marie reties the piece of tubing around my left bicep this time, and I give the stress ball firm rhythmic squeezes as she firmly smacks the crook of my elbow, searching for a point of entry. Beads of sweat are forming on Marie’s forehead now. She pushes the needle in and begins rooting around under the skin. I gasp in surprise at the sharp, clean pain as a tear spontaneously slides down my face. Marie looks horrified.

“I’ve been doing this for 25 years,” she says, “and you’re a tough one, my love. I’m so sorry, but I have to stop.” She pitches unsteadily forward toward the sink as she adds, “I’m having a hot flash.” She places a paper towel under a stream of water, and dabs at her neck and forehead. Apparently, I’ve just given my nurse menopause. “Would you like one too?” she offers, but I decline. She composes herself and asks, “Do you mind if we try it in your hand?” I look away as I feel the needle go in. I always thought “You can’t get blood from a stone” was a figure of speech. I am a stone.

Marie leads me now to the CT scan tube as she shrouds my warm blanket around me like I’m the James Brown of cancer, delivering a bravura performance. I lie on the table. “Take a deep breath,” an unseen voice commands. Seven seconds later it directs, “Let it out.” Easy for her to say. After a few more times like this, the technician comes in and adjusts my IV. A metallic rush of saline floods my mouth and an icy charge shoots straight up through the vein in my arm. Then there it is. The warm, pissed-in-my my-pants feeling strikes below. It happens every time, and every time I am positive I really have wet myself. It is the most mortifying conceivable possibility since I pooped a little on the bed somewhere in the throes of my first childbirth.

“You’re done,” the technician says. “Swing your legs around to the left and we’ll help you off.”

There’s no puddle on the table. There never is. I still have a year and a half of treatment to go.

Afterward, trembling with chills, I go around the corner to cup my hands around an oversized bowl of ramen, and absently poke the yolk of the egg that floats on top. My dessert is a sweet jewel of mochi ice cream. I am strangely touched by it, feel oddly nurtured, as if the weird dollop of whipped cream on a lettuce leaf was meant as comfort just for me, an offering from my surrogate Japanese mother. I feel fortified and in control. An hour later I am walking back toward the subway when Dr. Wolchok calls to tell me I’m still clear. I am six months cancer free. And when you’re on a virtually untested treatment protocol, it’s still quite a novelty.

In some ways, I did get the good kind of cancer after all. I realize it when I am talking to [leading immunotherapist Dr.] James Allison on a summer day, right near the anniversary of my diagnosis, about why melanoma has been such a source of interest to researchers. I’d assumed it was because, as [researcher] Nils Lonberg puts it, “There were no effective treatments for melanoma, so the immunotherapists were allowed to play in that little area. They weren’t crowded out by the non-immunotherapists, because there was just nothing there. We were given the playground that nobody else wanted to play in. We were dismissed. You would not believe it. It was terrible. At conferences we had the tiniest rooms.” But Dr. Allison offers me another reason. “You work with melanoma because it’s accessible. It’s a bad disease,” he says. “It has many mutations. People want to deal with it because it’s so bad. It’s rapidly fatal.”

It’s a vicious, unpredictable, and often swift-moving disease, and that makes it challenging to treat. It historically responds better to immune system-based treatments than other cancers have. And also, though Allison doesn’t come directly out and say it, if a treatment for it isn’t working, you’re going to find out pretty quickly. Because it’s rapidly fatal. That’s why when he tells me this, I start to cry. My horrible bad luck was my miraculous good fortune. I got the cancer that was intriguing to a bunch of geniuses, and I got it at exactly the right time.