The 2016 election cycle has led to heated discussion about the issues of money in politics and racial justice. However, these debates have rarely crossed: the dominance of the affluent and racial justice are treated as separate issues. My latest Demos report suggests that these debates are actually intertwined: the donor class is dominated by whites, which could hamper progress towards to racial justice.

While there has been some research examining the demographic composition of federal donors, there has been virtually none at the municipal level (one study examined the contribution patterns of Asian-Americans). The result is that the issue is rarely discussed, and the possibility that donors could skew policy is almost entirely ignored. To fill the gap, I worked with of University of Massachusetts-Amherst political scientists Brian Schaffner and Jesse Rhodes, and used Catalist, a progressive data vendor, to analyze the demographic composition of Chicago’s donor class. (Catalist’s accuracy has been independently validated and used in peer-reviewed articles and books.) The dataset includes all individuals that donated money (greater than the $150 disclosure limit) between May 16th, 2011 and April 7th, 2015. Catalist was able to match more than 90 percent of donors in the campaign finance data to their database.

The municipal donor class is incredibly white

The report shows that the donor class is incredibly white. Though the adult population of Chicago is 39 percent white, 82 percent of council and mayoral donors were. Emanuel relied the most on white donors, who made up 94 percent of his donors. Chuy Garcia, Emanuel’s opponent in last year’s Democratic primary, relied less on white donors; 39 percent of his donors were people of color. (27 percent were Latino.) Only 18 percent of council donors were people of color.

Women made up 30 percent of all donors, 27 percent of Emanuel donors and 44 percent of Garcia donors. People making more than $100,000 (15 percent of Chicago’s population) make up 63 percent of donors. Emanuel relied more heavily on the wealthy, and they made up four-fifths of his donors, compared to only 38 percent of Garcia’s donors. Fifty eight percent of council donors made more than $100,000.

This finding, that the donor class is overwhelmingly rich, white and male, meshes well with data on federal donors. An AP study of the 2012 election finds that 90 percent of donations came from white neighborhoods. Political scientist Michael Barber recently found that federal donors were overwhelmingly high income and high wealth. The extensive Demos report, “Stacked Deck,” also explored how racial disparities in the donor class affected policy.

More diverse in the middle

Although the disclosure limit in Chicago prohibits examining the small donor pool, the report examines the differences between medium and large donors. While donors between $150 and $999 were 73 percent white, donors giving more than $1,000 were 88 percent white. Among mid-level Mayoral donors, 67 percent were white. Among mid-level donors, 46 percent had incomes above $100,000, compared with 74 percent of the large donor pool.

Because the big donor pool is dominated by men, whites and the wealthy, it skews the total share of contributions coming from these groups. When examining the share of contributions (rather than share of donors) the disparities discussed become even larger. City council and mayoral candidates raised a whopping 93 percent of their money from whites, 78 percent from men, and 78 percent from those earning more than $100,000.

How affluence begets influence

Most of the reporting about money in politics is influenced by the data that are available. This still leads to great and important investigative journalism, but it leaves out important stories about the systemic race, class and gender divides in who donates to politics. OpenSecrets deserves credit for using what limited tools are available (“educated guesses based on biographical material available online”) to find that only 12 of the largest 500 donors in the 2014 midterm election were people of color. However, money in politics is a great example of how important and necessary stories can go untold because data aren’t available.

But even with the data that is available, the racial justice implications of money in politics are clear, but rarely articulated. Simply examining a list of the most powerful and influential donors on both the left and right makes it clear that politicians are spending most of their fundraising time listening to the concerns of an overwhelmingly white group. Indeed, President Obama discussed powerfully in his memoir,

“The Audacity of Hope,” a career spent concerned with the needs of the donor class can warp perspectives. It’s worth quoting at length.

President Obama writes,

Increasingly I found myself spending time with people of means — law firm partners and investment bankers, hedge fund managers and venture capitalists. […]

[T]hey reflected, almost uniformly, the perspectives of their class: the top 1 percent or so of the income scale that can afford to write a $2,000 check to a political candidate. They believed in the free market and an educational meritocracy; they found it hard to imagine that there might be any social ill that could not be cured by a high SAT score. They had no patience with protectionism, found unions troublesome, and were not particularly sympathetic to those whose lives were upended by the movements of global capital.

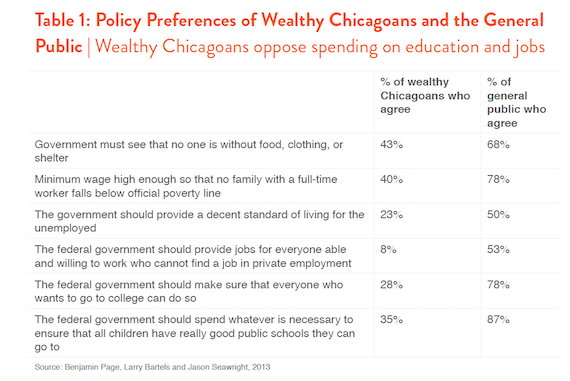

As I note in my report, this is almost identical to what political scientists Benjamin Page, Larry Bartels and Jason Seawright found when they interviewed high-wealth individuals for their Survey of Economically Successful Americans (SESA) study. They write of the rich,

“They are extremely active politically and that they are much more conservative than the American public as a whole with respect to important policies concerning taxation, economic regulation, and especially social welfare programs.”

Other politicians have complained about the rarified class they spend time drawing from contributions from, including Connecticut Senator Chris Murphy.

Such elbow-rubbing likely has an influence over policy in Chicago. Rahm Emanuel has been incredibly close to megadonor Michael Sacks, with whom he reportedly talks daily and has exchanged at least 1,500 e-mails. When surveying wealthy Chicagoans, the political scientists performing the SESA survey noted that,

Most of our respondents supplied the title or position of the federal government official with whom they had their most important recent contact. Several offered the officials’ names, occasionally indicating that they were on a first-name basis with “Rahm” (Emmanuel [sic], then President Obama’s Chief of Staff) or “David” (Axelrod, his chief political counsel).

The question is not necessarily quid pro quo corruption (i.e. “you scratch my back, I’ll scratch yours”), but rather a more subtle, more pervasive bias towards the preferences of the wealthy.

Conclusion

One solution to these inequities is a public financing system, either one that matches small dollar donations, one that gives qualified candidates a public grant or one gives all individuals a voucher to contribute. These systems have been shown to increase donor diversity, paving the way for more representative democracy. Public financing is already beginning to win, and as donors continue to dominate elections, will grow ever more important. By empowering the more diverse small donor pool, public financing could lead to more equitable policy making.