At first blush, the world already knows quite a lot about NYPD Officer Daniel Pantaleo. Video of him placing Eric Garner in a lethal chokehold is now a global symbol of police abuse.

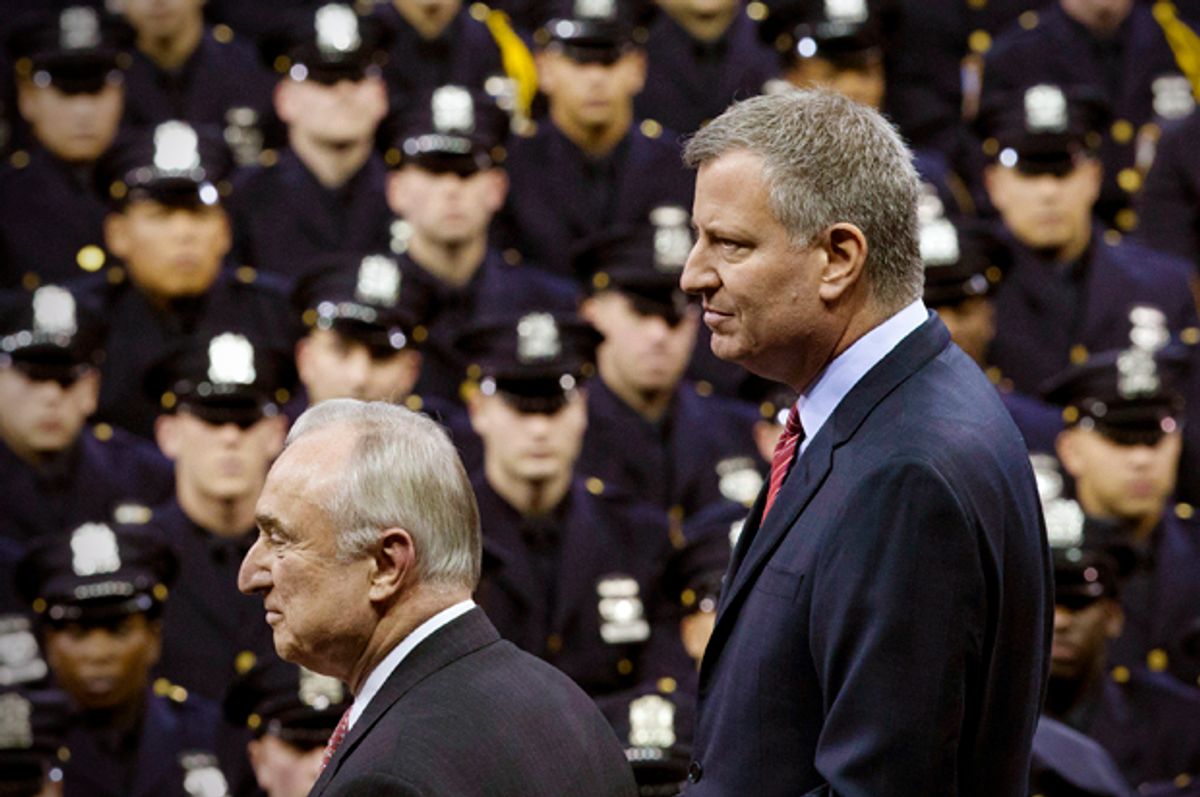

Yet the public still has close to no idea about Pantaleo’s track record before July 17, 2014, when he approached Garner, suspected of selling loose cigarettes, on Staten Island. That’s in part because New York Mayor Bill de Blasio’s lawyers are fighting to keep it a secret, citing a broad interpretation of a state law tightly restricting access to police officer disciplinary records.

“This law is part of a larger culture, a dual structure when it comes to accountability for police officers,” said Lumumba Akinwole-Bandele, senior community organizer at the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund. “The disparate kind of treatment that exists for law enforcement and non-law enforcement, community folks.”

Nearly two years after Garner’s death and the mass protests that followed, NYPD discipline remains shrouded in secrecy thanks to Civil Rights Law 50-a, which makes confidential most law enforcement and correctional officer “personnel records used to evaluate performance toward continued employment or promotion.” In February 2015, the Legal Aid Society filed a lawsuit against the Civilian Complaint Review Board after they refused to provide a summary of Pantaleo’s record, limited to information like the number of substantiated complaints against him and disciplinary action taken, in response to a freedom of information request.

“We simply want to know the most minimal information about whether or not Officer Pantaleo was the subject of civilian complaints and to what extent the city's mechanisms for discipline responded, or failed to respond, to those complaints prior to Mr. Garner’s death,” Legal Aid Society attorney Cynthia Conti-Cook wrote in a court filing.

Last July, New York Supreme Court Judge Alice Schlesinger ruled in Legal Aid’s favor and ordered CCRB to provide the summary. But de Blasio’s CCRB, along with Pantaleo, have appealed. In a statement, Law Department spokesman Nick Paolucci said that Judge Schlesinger’s ruling appears to contradict those made by other judges and that their “appeal seeks clarity and guidance from a higher Court.”

“Courts have recognized that Civil Rights Law 50-a balances two important values—protecting the privacy of officer records and ensuring public accountability for law enforcement officers,” according to Paolucci.

It’s unclear what de Blasio is up to, or what sort of balance his interpretation of 50-a affords. When pressed, spokesperson Monica Klein would not explain why the administration believes that their expansive interpretation of the police secrecy law is the correct one, or whether they support efforts in Albany to reform or repeal it. According to Klein, they are still “reviewing the potential impact of this legislation.”

“It’s a political decision by the city to characterize their opposition as ‘clarity seeking,’” says Conti-Cook. “Lawyers don’t seek clarity, they argue,” and the city is in this case “arguing for a stricter interpretation of 50-a.”

In another case, the city is fighting the New York Civil Liberties Union’s efforts to gain access to decisions in NYPD discipline cases. The city, citing the police secrecy law, argues that those records are confidential even though the trial-like hearings are open to the public.

“The city goes to great lengths to use 50-a to keep documents from public view,” says Christopher Dunn, associate legal director of the NYCLU. “Unless you’re prepared to litigate, for many people that’s going to be the end of the line.”

In a separate case, the city is defending against a lawsuit filed by a Rikers Island guard making a futile effort to hide his unsavory disciplinary history, which was made public after he appealed a finding against him to a city administrative court. The NYCLU has filed an amicus brief, and The New York Times has intervened in the case, to challenge the corrections officer’s claims that he is protected by 50-a. Notably, the city has fought that lawsuit on procedural grounds and avoided discussion of the police secrecy law.

In court, city lawyers are representing the police oversight board. But Conti-Cook says their advocacy seems more like it is geared to protect the very police department they purportedly oversee.

For roughly one year, until October 2014, New York City’s Civilian Complaint Review Board released barebones summaries of officer disciplinary records in response to freedom of information requests, including the number and nature of complaints and whether they had been substantiated. That tiny window of transparency, according to a CCRB report, was slammed shut after an internal audit found the disclosures to be in violation of 50-a.

The disclosures, according to an unfriendly New York Post story, were made by former CCRB head Tracy Catapano-Fox. Catapano-Fox was ousted in 2014 in what she contends was retaliation for her questioning the CCRB board chair’s “decision to collude” with the NYPD to fudge statistics on stop-and-frisk and push against investigations of wrongdoing. Catapano-Fox also accused a board member of sexually harassing a female employee, and contended that the mayor’s office interfered with her application to become a judge. In May, the city settled for $275,000 but admitted no wrongdoing.

New York’s police secrecy law dates to 1976, passed in response to complaints that defense attorneys were using police records to embarrass officers. As Legal Aid coolly noted, Garner’s personal record had received no such courtesy.

"Unlike Mr. Garner's entire arrest history that has been released post-mortem with detailed charges thoroughly digested by the news media, regardless of presumption of innocence or statutory privacy protections...the overall restricted summary requested here would merely indicate the number of prior civilian allegations, complaints, charges and outcomes brought against Mr. Pantaleo prior to Mr. Garner's death."

The law produces surreal results across New York. In 2011, Nassau County Police Officer Anthony DiLeonardo, off duty with a long night of drinking behind him, shot and injured a cabbie, allegedly fleeing and unarmed, after a traffic dispute. Though an internal affairs investigation found that DiLeonardo had been in the wrong, he was not suspended or prosecuted. It was only two years later that a Newsday reporter, according to the paper, “found that the internal affairs report of the incident had been accidentally left unsealed in the court file of a $30 million federal civil-rights lawsuit.”

According to Newsday, it was only after their investigation was published that Suffolk County District Attorney Thomas Spota empaneled a grand jury to look into the incident. The grand jury never issued an indictment. Spota’s actions in that case and others are now reportedly the subject of a federal investigation. When DiLeonardo was finally fired in 2014, the police commissioner cited 50-a and declined to discuss his disciplinary record in any detail.

In New York City, WNYC received data, with no names attached, that showed how many officers had received a given number of complaints. Reporter Robert Lewis found that “a relatively small number of cops generate the most civilian complaints — and the department routinely ignores recommendations on how to discipline the worst of them.”

But he couldn’t identify who these problem officers were.

“50-a was a huge obstacle in reporting these stories,” Lewis emailed. “After the death of Eric Garner a lot of people, including me, wanted to know about the officer involved in the incident. Did he have a history of using excessive force? Had he been disciplined before? Should he have been on the street? But those questions were virtually impossible to answer in large part because of that law…Aggregate data is helpful. But a deeper analysis and examination of a system is often only possible if the public can examine the disciplinary history of specific officers.”

In 2014, the Committee on Open Government, an independent state agency, called for the legislature to make repealing or reforming 50-a a priority, writing that the law “affords the public far less access to information about the activities of police departments than virtually any other public agency—even though police interact with the public on a day-to-day basis in a more visceral and tangible way than any other public employees.”

Assemblyman Daniel O’Donnell, a Manhattan Democrat, heeded the call, and has introduced separate legislation to reform and repeal the law. The measures stalled in the Democratic-controlled state House and went nowhere in the Republican-controlled Senate—which, in a New York peculiarity, Democratic Gov. Cuomo uses as leverage against his own party. Cuomo’s office did not respond to requests for comment.

It’s unclear where Cuomo stands on 50-a reform and repeal. O’Donnell says he doesn’t know either, and was incredulous when asked whether he had discussed the matter with the governor.

“You’re kidding, right? You think the governor conversates with people like me? He either calls you to yell at you, or tell you you’re wrong. But he doesn’t conversate about legislative proposals.”

Other states and cities do things differently.

In Illinois, police disciplinary records are now subject to freedom of information requests thanks to a successful legal fight mounted by Jamie Kalven, who directs the Invisible Institute, a Chicago civic journalism project. It was just two weeks after the Invisible Institute launched its Citizens Police Data Project that a separate freedom of information request compelled Chicago to release video of Officer Jason Van Dyke shooting teen Laquan McDonald sixteen times as he walked away. The resulting uproar created a political crisis for police and Mayor Rahm Emanuel.

And unlike in New York, Chicagoans could dig deeper. Journalists were able to report that a large number of misconduct complaints had been filed against Van Dyke. By contrast, New Yorkers still have little idea as to Officer Pantaleo’s track record.

“Chicago had the opportunity to respond to the systemic failures because they had the information,” emails Conti-Cook. “NYC doesn’t have access to the information and cannot analyze whether systemic failures played a role.”

Police Commissioner Bill Bratton has insisted that the department will “work very aggressively to deal with” those officers too brutal or corrupt to be on the force. There is little way, however, to know whether they are doing so. Even amidst the mass protests following Garner’s death, de Blasio has failed to make the NYPD disciplinary system, widely criticized as ineffectual, more transparent. Among Bratton’s responses to Garner’s death: a proposal to increase the penalty for resisting arrest, which Garner was accused of doing before he was killed by police, from a misdemeanor to a felony.

The police secrecy law also makes it hard for defense lawyers to access disciplinary records needed to question an officer’s truthfulness on the stand. At Legal Aid, Conti-Cook has set up a database comprising whatever publicly available information they can glean about an officer’s track record from lawsuits, news reports and other sources. Currently, she says, prosecutors typically do not hand over such information on their own during criminal trials, and defense lawyers have to convince a judge to order the release of records the existence and content of which they can only speculate about.

In New York state, toppling Republican rule in the senate might clear a path for reform and force Cuomo’s hand. In the city, advocates must change de Blasio’s calculus so that he views police critics as a bigger political threat than the New York Post and Patrolmen's Benevolent Association.

“Every year it seems that events occur that lead me to believe that maybe now is the time, whether its Ferguson or Pantaleo, or one of these terrible events” says Robert J. Freeman, the executive director of the Committee on Open Government. “Isn’t it time to either repeal or amend 50-a to make sense? And yet my belief is that the police union, and also the correction officers’ union, they scare the state legislature. And for the life of me I don’t know why.”

The balance of power, real and perceived, keeps the public in the dark.

Shares