“Peace, peace!” wrote Percy Shelley in the climactic stanza of his great poem about the death of his friend and rival, John Keats. But Shelley’s poem, “Adonaïs,” is not about peace — rather the opposite. If anything, it’s about the strife and anguish from which human life is never free.

He is not dead, he doth not sleep,

He hath awaken'd from the dream of life;

'Tis we, who lost in stormy visions, keep

With phantoms an unprofitable strife,

And in mad trance, strike with our spirit's knife

Invulnerable nothings. We decay

Like corpses in a charnel; fear and grief

Convulse us and consume us day by day,

And cold hopes swarm like worms within our living clay.

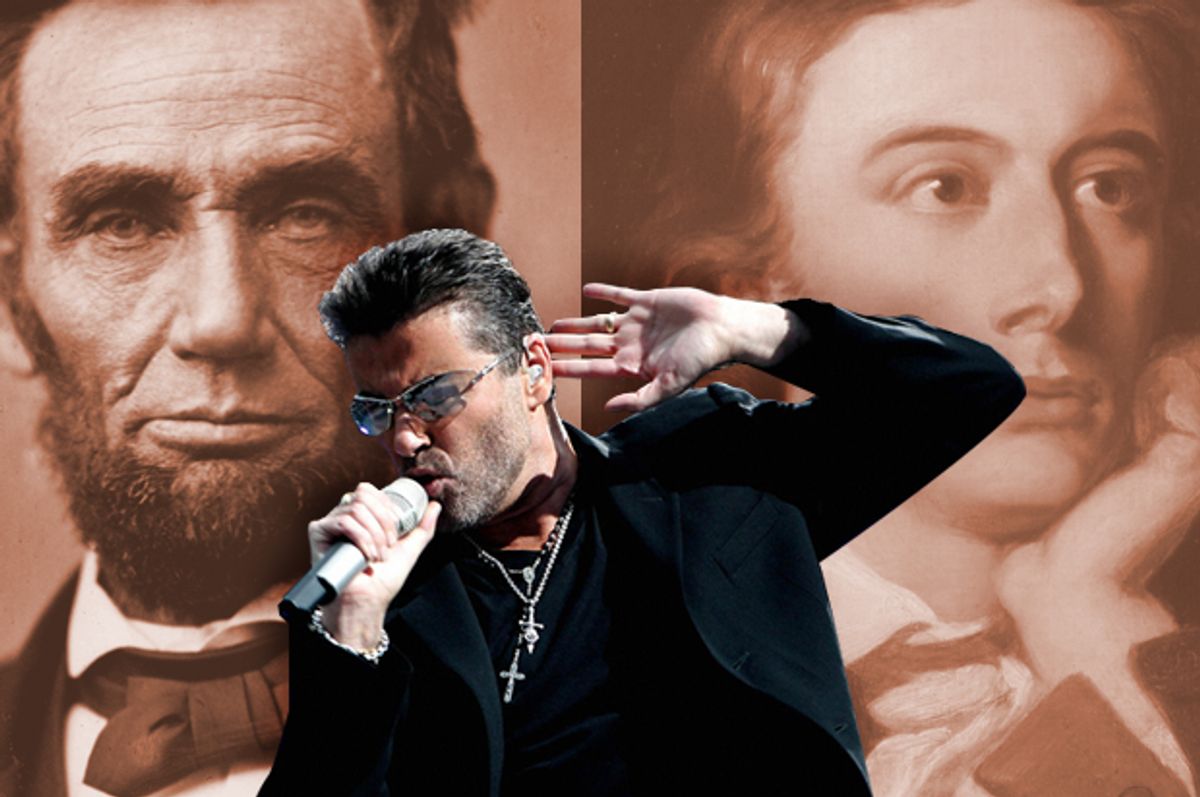

This is a form of consolation common to poetry and religion, one much in demand over the past 12 months as we have lost David Bowie, Muhammad Ali, Prince, Leonard Cohen, Alan Rickman, George Michael, Carrie Fisher and Debbie Reynolds (just off the top of my head) and have suffered the not-entirely-metaphorical death of our democracy, which has been sick far longer than any of those people. If you grew up amid Anglo-American pop culture of the 1970s and ’80s, and if you once held a burnished view of American tradition and American possibility — that describes, I think, a large number of people — this has been a tough year. I can’t promise I can make any of it better, but I can assure you that all the emotions we now feel have been felt before. Maybe that counts for something.

Confronting the mortality of famous people is always a way of confronting our own, I suppose, just as the tales of their marriages and divorces and affairs seem to echo and deepen our own histories of relationship success or failure. If you belong to the micro-generation that assumed that most of the people on that list would always be part of our lives, as I do, then 2016 has offered an especially pungent reminder that there is no such thing as “always,” and that our day is coming sooner than we would like. If your year was also not easy for other, more personal reasons (as mine certainly was), that seems to go with the territory.

As a child, I rushed out to the driveway for the newspaper on the morning after Ali’s big Madison Square Garden fight with Joe Frazier, and was crushed to learn that the mighty hero had fallen. A few years after that, Bowie’s late ’70s records offered me my first glimpse into a realm of bohemian adventure that actually existed, in real life and on the same continent where I lived, and not just in books about the 1920s or the 19th century. Add a few more years, and Prince emerged as the perfect distillation of white and black pop, a symbol of racial and cultural liberation sent to free us from the Reagan years. I didn’t learn to appreciate Cohen’s music until adulthood, when (again, along with many other people) I realized that he was not some folk-rock phenomenon constrained by the ’60s but something closer to a modern-day prophet.

Each of them, like the other people on that list, had a long and complicated life with many conflicting currents, and I won’t even try to do justice to that complexity here. But it did not occur to me that I would live to see them all dead, or that those deaths would all occur in a year that had so many other ways to make us mourn for lost time and lost opportunities, so many ways of reminding us that time is fleeting, and to gather our rosebuds while we may.

I didn’t have the same personal relationships with other people on that list, or with others I haven’t mentioned (Edward Albee or Elie Wiesel or George Martin or Gloria Naylor or Maurice White or Mose Allison — we could go on). But you may, and people each of us knows almost certainly do. Someone close to me was really broken up over Alan Rickman, who was one of the greatest screen and stage actors of our time, and I don’t begrudge anyone, gay or otherwise, for perceiving George Michael as a sui generis figure -- a Keatsian figure, if ever there was one -- who broke new ground in pop music. (“Listen Without Prejudice Vol. 1” is simply a great record, so great it seemed to have defeated its creator in some ways.)

I don’t want to dwell too much on the perhaps-terminal decline of American democracy, which this publication and everyone else in the media has been worrying over for the last year and a half, like a dog with an old mutton bone. It’s not as if people who supported the incoming president are incapable of grief and sorrow (although I suspect they are underrepresented in the Bowie and Prince fanbases). But for many of us the inexplicable political events of 2016, which remain difficult to believe, even now that they have happened, are at once the atmosphere, the subtext and the inner meaning of all this death. I was not an especially avid supporter of Hillary Clinton, but for many American women (and men) the perverse tale of how she was denied the presidency yet again in her final campaign is another of this year’s great losses. The vision of a woman president came so close to reality, but remains a dream deferred.

We have a way, as human beings, of staring into the darkness and seeing light. We’re going to need that now. In some ways, what Shelley has to tell us in “Adonaïs” is highly conventional: Whatever you believe awaits us on the other side — something or nothing, heaven or hell — at least the struggles of this life are over. Mourning is essentially a form of self-indulgence; it is we who suffer, not the dead. Shelley wrote that poem, of course, while still amid the mad trance of life, locked in unprofitable strife with phantoms: He had one eye on his dead friend and the other on posterity, and was clearly trying to go head to head with John Milton’s “Lycidas,” written nearly two centuries earlier, the first really famous pastoral elegy for a dead friend in the English tradition.

Weep no more, woeful shepherds, weep no more,

For Lycidas, your sorrow, is not dead,

Sunk though he be beneath the wat'ry floor;

So sinks the day-star in the ocean bed,

And yet anon repairs his drooping head,

And tricks his beams, and with new spangled ore

Flames in the forehead of the morning sky:

So Lycidas sunk low, but mounted high

Through the dear might of him that walk'd the waves ...

Milton refers us back to Christian redemption as the reason not to feel depressed about death and loss, or at least he thinks he does. (I’m inclined to argue that he invented Romanticism without meaning to, and was constantly at war with his own faith.) But the idea at work here, that light must come out of darkness and hope can be found amid deep personal despair — the belief in literal or allegorical transcendence — is such a cultural constant across literary and religious traditions that it has to mean something. Admittedly, that “something” might just be that biology drives us onward, and those of us who find ourselves still living while others die make up reasons to keep going, because our brains are over-evolved and we can’t help thinking about these things. Cats and beetles, so far as we can tell, don’t ask themselves these questions.

Friedrich Nietzsche’s famous maxim that “what does not kill me makes me stronger” has been repurposed so much by football coaches and military strategists that its original ambiguity has gotten lost. Like most of the mad German’s pronouncements, that one is double-edged and purposefully unclear. Nietzsche knew from experience, for example, that physical illness does not make you stronger in any ordinary sense. (That passage, in fact, comes from “Twilight of the Idols,” his next-to-last major work.) I take his statement to mean that confronting death and mortality directly, as we draw nearer to our own deaths, fortifies us to better use the hours and days we have left.

Nearly everyone I know is coming out of 2016 beset by deep feelings of grief and loss. If we have been made stronger in that sense, we will be more than strong enough for whatever lies ahead: death or transformation, political or cultural or personal. Walt Whitman was thinking of something like this, in a more optimistic key, in perhaps the greatest of his poems, “When Lilacs Last in the Dooryard Bloom’d.” He imagines making friends with death, holding hands with death, and even arriving at “a sacred knowledge of death,” as a way of dealing with the assassination of Abraham Lincoln (named in the poem only as “him I loved”), a grievous loss that did not quite kill America and may, for a while, have made it stronger.

And the streets how their throbbings throbb’d, and the cities pent — lo, then and there,

Falling upon them all and among them all, enveloping me with the rest,

Appear’d the cloud, appear’d the long black trail,

And I knew death, its thought, and the sacred knowledge of death.Then with the knowledge of death as walking one side of me,

And the thought of death close-walking the other side of me,

And I in the middle as with companions, and as holding the hands of companions,

I fled forth to the hiding receiving night that talks not,

Down to the shores of the water, the path by the swamp in the dimness,

To the solemn shadowy cedars and ghostly pines so still.

Shares