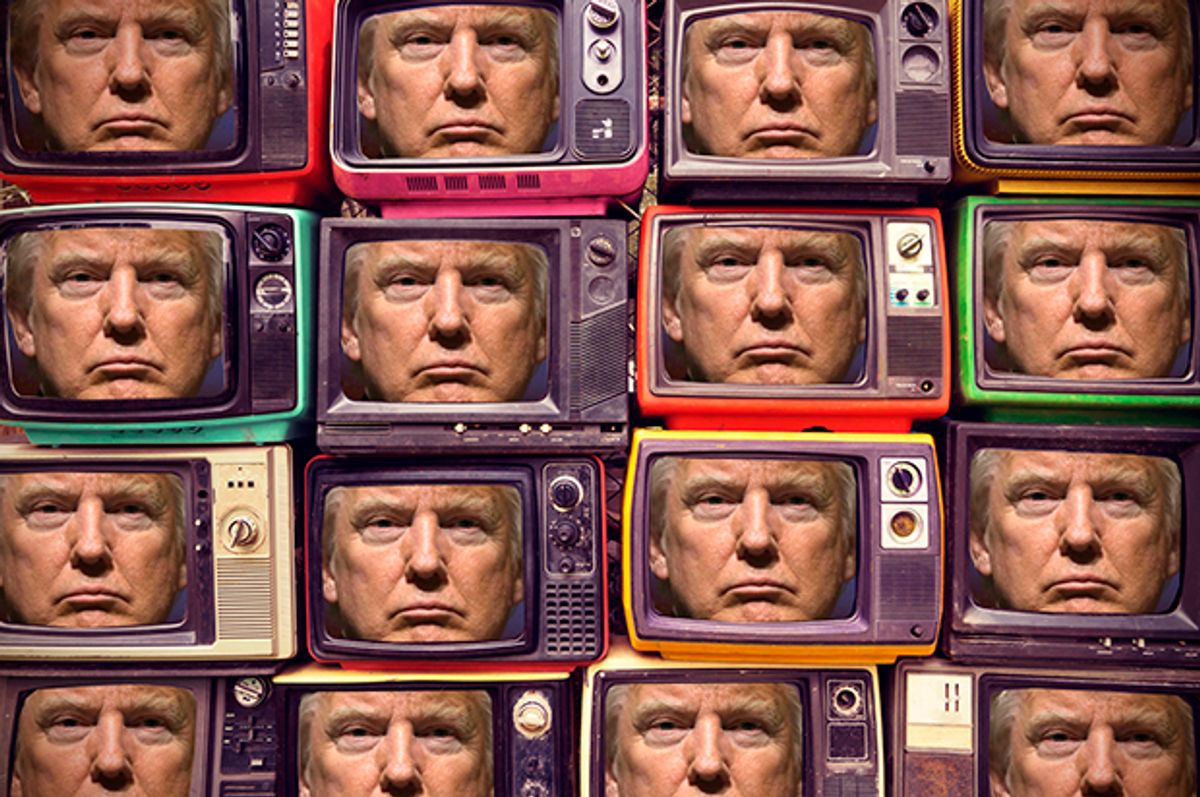

Faced with the presidency of a master media manipulator unlike anyone else in political history, what can the media do to counteract his dark magic? I'm not a big fan of self-congratulatory essays about the importance of journalism, but this is a central question in the current crisis of democracy.

If Donald Trump has accomplished nothing else in his first six weeks in the White House, he has galvanized the latent oppositional tendency within the mainstream media. The New York Times has repeatedly denounced Trump in front-page headlines for telling lies, breaking a long-standing precedent. Washington Post reporters continue to break news about the lengthening list of Trump associates who apparently had contact with Russian officials during the 2016 campaign, a murky scandal that will continue to unfold as long as Trump is president.

There was widespread outrage when White House Press Secretary Sean Spicer sought to punish CNN, the Times and other “unfriendly” news outlets by barring them from an official briefing, and most journalists who attended the briefing said they regretted it afterward. Even network news reporters and anchors, schooled from their earliest days on the job to adopt a bland, breezy, pseudo-analytical neutrality, have notably moved toward a more confrontational mode.

Being described as enemies of the American people and the most dishonest humans on the planet will provoke that reaction, I guess. This is without question a big improvement on the way Trump played the press like a Stradivarius during the presidential campaign, and media coverage of the Russia scandal is unmistakably making him unhappy. Since we’re on that topic, I would encourage both the media and the public to learn from recent mistakes and acknowledge the immense extent of what we don’t know and can’t see. It seems entirely conceivable, for instance, that there was some degree of collusion between the Trump campaign or the Republican Party and Russian hackers. It also seems conceivable that the CIA or other “deep state” operatives are now trying to destabilize Trump’s wobbly regime for their own reasons. Both things could easily be true.

In any event, the inescapable problem with the media’s newfound display of spine and spirit is that we’re still playing the game on Trump’s court and under his rules. To put it another way, journalists are laboring under a larger version of Charlie Brown’s epistemological delusion when faced with Lucy and that football: We keep on thinking that sooner or later the normal order of things will be restored, and we’ll get to kick it. But as Thomas B. Edsall recently observed in an essential New York Times column, social media and the Internet have radically destabilized the norms and practices that have governed American politics for at least the last 60 or 70 years: “They have disrupted and destroyed institutional constraints on what can be said, when and where it can be said and who can say it.”

We can debate whether that’s a good thing or a bad thing, and despite his perch at the Gray Lady, Edsall acknowledges that the evidence cuts both ways. But in terms of Trump and the media, the most important consequence is that the mainstream media’s power to define truth, and to set the limits of acceptable political discourse, has been largely destroyed. Only now, long after the proverbial horses have fled the barn, are journalists beginning to understand the enormity of this change, and nobody has any clear idea what to do about it.

If the Times or the Post (or Salon) reported tomorrow that Donald Trump was deeply in debt to shadowy Russian billionaires and had received direct instructions from Kremlin spymasters, how many of his supporters would notice, believe it or care? Of course I believe such a story would be worth reporting, and of course I believe (or at least hope) that the vestigial machinery of democracy would be forced to respond.

But honestly, who knows? In a universe shaped by the blatant untruths and racist fantasies of right-wing media, where Barack Obama’s birthplace was a mystery, the Sandy Hook shootings might have been staged and millions of people who were not obviously suffering from severe mental illness took the Pizzagate “scandal” seriously, the difference between news and fake news comes to seem like a matter of taste or opinion. Edsall quotes Samuel Greene of King’s College London to the effect that the crisis of democracy is not happening because “our information landscape is open and fluid, but because voters’ perceptions have become untethered from reality. . . . Thus, the news we consume has become as much about emotion and identity as about facts.”

Donald Trump has both nurtured and mastered this crisis of perception, in which truth is a relative construct and facts are whatever you want them to be. But diabolical as he may be, Trump didn’t create this brave new world on his own. It was a long time coming, and the institution of journalism itself must bear part of the blame. Those of us who have been around the block a few times believed we had encountered hostile presidential administrations before, who were averse to facts and eager to divide and rule through propaganda. Now it turns out that Nixon, Reagan and George W. Bush were little more than warmup acts, Borscht Belt showmen who got us ready for the greatest insult comic of all time.

For a politician to take his inspiration from the realm of showbiz celebrity is not new, but most of us operated on the assumption that a “conservative” presidential candidate was likely to model himself on Gary Cooper or John Wayne. Donald Trump’s peculiar genius may lie in having figured out, long before anyone else, that the aspirational model for American males of a certain age and class (and race) was no longer those guys but Andrew Dice Clay.

Other, more important assumptions turned out to be mistaken as well. Before the rise of Trump, much of American journalism was mired in a strange combination of heroic myth and dull-witted conventional wisdom. On the one hand, we were the guardians of democracy, and the sunlight we provided would eventually cure all possible infections. Everyone who does this job knows about Watergate and the Pentagon Papers and Edward R. Murrow standing up to Joe McCarthy (and tries to forget about Judith Miller and dozens of other counter-examples). On the other, the range of possible outcomes in American politics was understood to have narrowed down to a center-right pragmatism where many fundamental questions — about the nature of our economy, or about America’s role in the world — were hardly ever discussed.

In retrospect, it seems abundantly clear that those things were in contradiction, and ended up effectively canceling each other out. Journalism’s idealized sense of its own mission as a courageous and independent instrument of truth was not compatible with its truncated and narcissistic view of reality. This problem has been with us for years; I’ve written previously about the “Jon Huntsman syndrome,” in which media pundits focus on some middle-way candidate they believe is perfectly suited to the American electorate, only to discover with bafflement that the American electorate isn’t interested.

One way of explaining what befell the media in 2016 is that Huntsman syndrome reached terminal proportions. Past was taken as prologue, or rather an interpretation of the past was seen as defining the future. Many journalists assumed they knew what would happen because they already understood the kinds of things that could happen.

Punditry and polling became seen as prophecy, an especially dangerous combination in an age when the difference between data and bullshit is nearly impossible to discern. Reporting, in too many cases, became the unglamorous handmaiden to that prophecy. A great deal of reporting on the 2016 campaign was essentially done backwards or upside down: Instead of carefully building a picture of the truth from the available evidence — however conditional or imperfect that picture might be — journalists looked for evidence that supported what they already believed to be the truth.

Certain possibilities were excluded from serious consideration, because the media tribe had self-indoctrinated with the doubly false creed that American politics had always worked a certain way and always would. That a self-described socialist — and a weird-looking old guy at that — would very nearly steal the Democratic nomination from the party’s official president-in-waiting was laughable. That a billionaire demagogue with no discernible ideology and no political experience would defeat more than a dozen credentialed Republicans and then be elected president was even more so. I’m pretty sure David Brooks wakes up every morning and turns on his Bose bedside radio in hopes he will discover that the “Twilight Zone” episode has ended and he has returned to the real world, where Jeb Bush or John Kasich is president and people are feeling a little better about the Protestant work ethic all the time.

Of course it’s not fair to suggest that all journalists shared identical assumptions or reacted in the same way. I was excoriated in private some weeks ago by a prominent TV news personality for painting with too broad a brush in an earlier article. There were many reporters in print and online media, on cable or network news, who recognized that Trump’s candidacy presented unique dangers and challenges, and did their best to combat him with the tools they had available.

But their toolbox, by definition, remained within the old epistemological frame of news media, in which clear information and rational argument would carry the day. Trump’s campaign represented the smashing of that old frame and the leveling of all forms of information, so that the distinction between fact, opinion and emotion was no longer perceptible. It was as if postmodern critical theory, the weapon of post-Marxist academics in the ’80s and ’90s — which understood all forms of communication as modes of power and control — had fallen into the hands of the enemy and fulfilled its historical mission in ironic fashion.

My point is that as a general tendency, the institution of journalism set the stage for its own failure in 2016, and every form of media coverage provided to Donald Trump — good or bad, shameless or indifferent — only fed his legend and fueled his victory. So when Trump derides the “failing” New York Times, or tweets that the “FAKE NEWS media” is “the enemy of the American People,” he touches a nerve in a way he probably doesn’t understand. There is no doubt that the mass media has lost most of its once-monolithic power over information, and I would suggest it has tried to adjust to this new reality in the worst possible way, by anointing itself as a priesthood of enlightened opinion and received wisdom, which turned out to be worth less than the bandwidth it used up.

If the news wasn’t fake, exactly, the institution charged with reporting and delivering it was definitely full of crap in a big way. It’s not at all clear how the media climbs out of the Heffalump Trap it dug for itself and then fell into, or how best it can fight back against Trump’s masterful milking of his supporters’ incoherent anger and resentment. Abandoning the conventions of “access journalism” and enforced middle-middle objectivity for a more directly adversarial stance — no matter who’s in power — is surely a good start.

I started writing this essay with the intention of responding to a special issue of The Nation on “Media in the Trump Era,” published in conjunction with the Columbia Journalism Review and guest-edited by veteran progressive press critic Mark Hertsgaard, which seeks to launch a discussion on precisely that topic. That issue deserves more attention than I can possibly give it here, and will have to wait for another installment. My concern is that we can't leap ahead to solutions if we don’t take the time to figure out where the hell we are and how we got here. The American media trying to find its way back to first principles under President Donald Trump is in a tragicomic situation, something like a guy who wakes up chained to a bed inside a locked room in a burning house, and decides he’s finally going to quit drinking.

Shares