We love our antiheroes. From Tony Soprano to Walter White, we can’t get enough of beguiling, flawed men who do bad things but win our affection. But when it comes to antiheroes in documentary films, that sort of fandom can get tricky. "Fog of War" cast Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara, who helped engineer the war in Vietnam, in a whole new light. "Making a Murderer" has made a hero (to many) of a man convicted of brutally murdering a young woman.

A new documentary, "The Skyjacker’s Tale," asks viewers to take a closer look at Ishmael Muslim Ali, a man from the Virgin Islands convicted, along with four other men, of a mass killing of eight people on a Rockefeller-owned golf course in 1972. After serving 12 years in prison, he then hijacked an airplane on New Year’s Eve, 1984, and ended up in Cuba where he served another seven years in prison.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?time_continue=1&v=2ydbAhwJ4MI

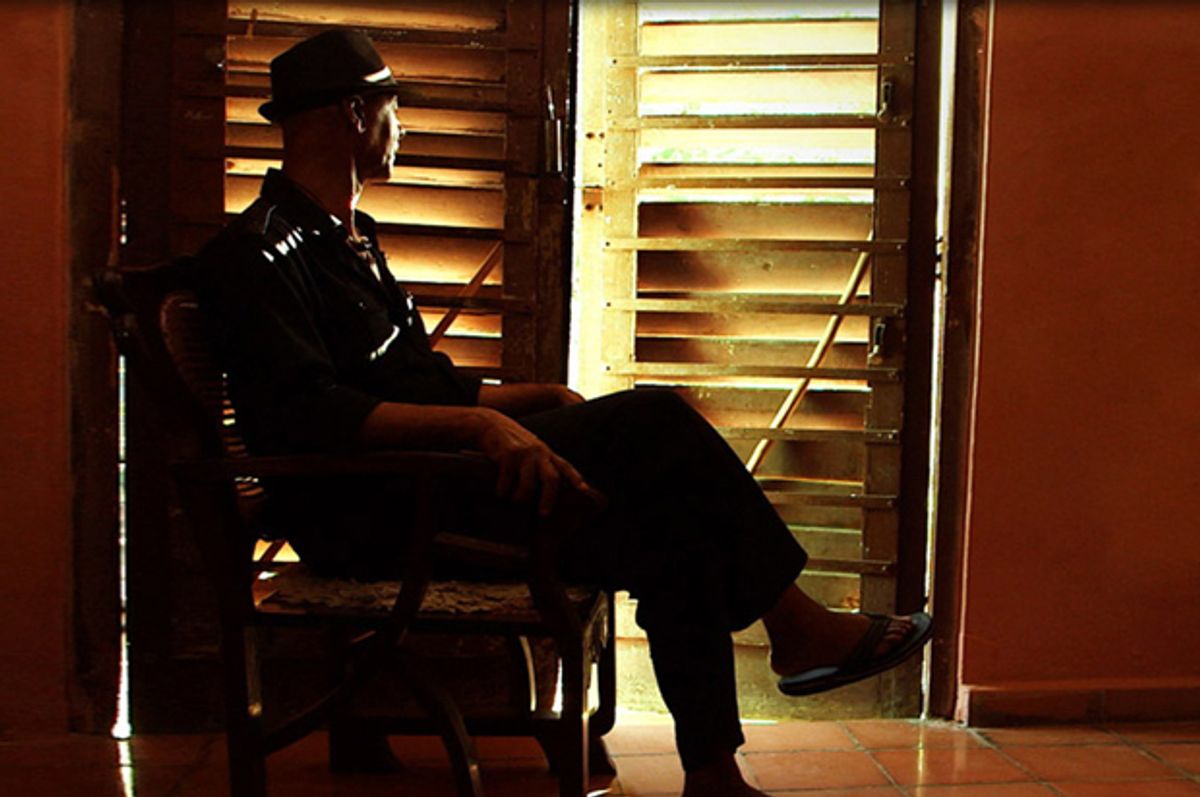

Now a free man in Cuba with a family, he is indeed a fascinating character with a documentary to match. Did he do it? Is he a victim of a political and racist system? The questions linger.

Salon asked the director of "The Skyjacker’s Tale," Jamie Kastner, to discuss his riveting story of a complex man who is as captivating a character as any that show runners David Chase or Vince Gilligan might dream up. (Spoiler: There are no easy answers.)

How is this story relevant today?

"The Skyjacker’s Tale" is extremely relevant today on a number of fronts. President Trump has just demanded as a key part of his Cuba policy that U.S. fugitives be returned. The film’s protagonist, Ishmael Muslim Ali (formerly LaBeet), is one of the top five most wanted U.S. fugitives who have been granted asylum in Cuba, out of an estimated 70 to 80.

The film grants the opportunity to actually get to know a key member of this vilified, fascinating group — sore thumb of the Cold War that it is. The film shows you the man, and the remarkable story that got him to Cuba.

Prior to the hijacking that got him to Cuba, Ali was one of five black men convicted of murdering eight people on a Rockefeller-owned golf course called Fountain Valley, in the U.S. Virgin Islands, in the '70s. During their remarkable trial, at which they were represented by top civil rights lawyers including William Kunstler (hot off the Chicago Seven trial), Margaret Ratner and Chauncey Eskridge, it was argued that they were wrongfully charged and convicted. What was revealed during the trial about what happened during the arrests and interrogation is shockingly familiar. In the era of Black Lives Matter, this story feels as though it could’ve been ripped from last week’s headlines.

Do you think that Ishmael Muslim Ali committed the Fountain Valley killings?

Ultimately, whether Ali committed the crime isn’t what the movie is about. It’s about the justice system and how it works or doesn’t work, and how one man took matters into his own hands — the right and wrong of it is for the audience to decide.

What was it like shooting in Cuba? What status does Ali have in Cuba?

Shooting in Cuba was fascinating, somewhat cloak-and-dagger, truly a different Caribbean experience, to say the least. We were cautious during the shoot, but by no means felt endangered or encountered any significant hassles. Ali has been granted political asylum there; he’s a permanent resident.

Your portrayal of Ali is complex; how would you respond to a viewer or a family member of one of the Fountain Valley victims who might say your film is too sympathetic toward Ali?

It was extremely important to me, from the beginning, to maintain a standard of journalistic rigor and include a comprehensive range of views in the film, however much it may stem from Ali’s “tale.”

Given the crime goes back 40-plus years, my research team found a remarkable number of people who could speak firsthand to all aspects of the story, and represent both sides.

There are a number of people in the film who take a disparaging view of Ali, contradict his version of events; all these people are given a fair shake.

In fact, many people see the film and don’t find him to be sympathetic at all. I don’t care, as long as they are engaged by the story.

For some viewers I suppose he could never be painted negatively enough. … I feel a reasonable balance was struck.

Despite — or because of — your diligent and measured portrayal, the truth seems elusive about a case and man that screams for clarity. Are you comfortable with the fact that your story doesn’t provide a definitive answer?

Certainly it’s a complex story, and he’s a complex person, but to me that’s part of its unique appeal. The audience must, as I did making the film, question at every turn what it really believes, stands for, and why. The aim was to create a sort of intellectual/emotional/moral thriller using a whodunit setup. But it’s a faux whodunit; it turns into something else, and there are no easy answers. As in a trial, you are presented with the evidence, and must reach your own conclusions.

Do you think Ali will be extradited?

I think it’s a distinct possibility. After all, Obama’s initial announcement was accompanied by an exchange of U.S. and Cuban spies. I’m not sure things are any safer under Trump for the fugitives. Both sides are talking tough, but if push really came to shove, if sending a few folks home were the price of ending an embargo that has punished the entire Cuban population for 60 years, how far would they really be prepared to go?

Despite his cool demeanor, does the threat of extradition cause him any distress?

Ali is a gentleman of the old school, which is to say, rather macho when it comes to expressing his fears. But I believe the prospect does, certainly, cause him distress. He has a family in Cuba, a partner, kids, grandkids … a whole life. If he were to lose that family, it would be the second he’d have lost in a lifetime. And to be returned to prison in America at his age — how could all that not be devastating? But to be fair, given the remarkable amount the guy has survived — 20-odd years in some pretty hardcore prisons, not to mention the hijacking itself — maybe it’s not all just tough talk. He would have to have developed a certain Zen to have made it this far.

Shares