The story reads like an outline for a new David Simon series — equal parts seedy, titillating and tragic. The FBI's been building a federal case exposing widespread corruption among multiple NCAA powerhouse universities with evidence gathered through wiretaps, informants and undercover agents. So far, nearly a dozen arrests have been made in relation to two systems of alleged bribery and fraud: university assistant coaches allegedly accepting bribes to steer their players toward specific advisers if and when they join the NBA, and another channel allegedly allowing a company that's been identified in the press as Adidas to bribe college recruits to commit to certain affiliated university teams and then later to align themselves with the company after they go pro.

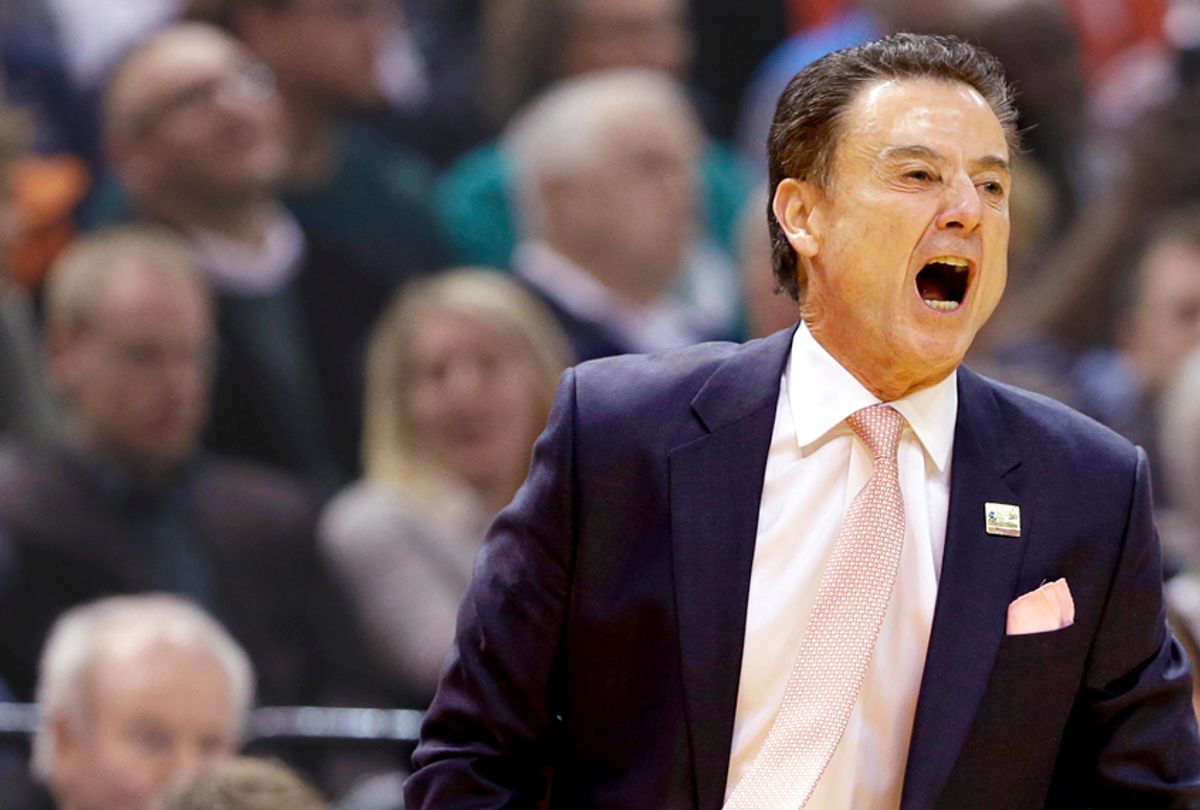

One of the biggest fallouts so far has been the unpaid suspension of University of Louisville head coach Rick Pitino, whose mighty on-court successes have been marked by scandals both personal and professional, after Louisville was linked to one of the pay-for-play investigations. Barring a reprieve, Pitino, who denies involvement, is expected to be out officially next week.

These alleged under-the-table dealings, which acting United States attorney Joon H. Kim describes as "the dark underbelly of college basketball," stand in stark contrast to the wholesome thrills of the annual March Madness tournament, when civilians become bracketologists, enthralled with the romantic ideal of talented kids leaving it all on the court, playing for glory and legacy with nothing but heart.

How widespread are dark-money deals? It's hard to say, but anyone who's paid even a lick of attention to the college ball industry can't pretend to be surprised that they happen. In an industry where everyone's getting paid handsomely and legitimately except the people most essential to the enterprise — you can't coach, analyze or broadcast an empty court — money is going to find its way to some of them, the way money always does, out of need or temptation or both.

And why shouldn't it, albeit without the skullduggery? The case that players should be paid fairly for their labor has been made cogently and loudly by many, notably by "Indentured" author and veteran journalist Joe Nocera, who asks in a Bloomberg column this week why the FBI is "doing the NCAA's dirty work" in this investigation, if these are rules violations, not federal laws, that have been broken. The NCAA's amateurism rules are hypocritical, counter-productive and unnecessarily punitive. The league and the university athletic programs make billions off of young people, mostly young men of color, some of whom — though not all — also hail from families who have nothing left to sacrifice, whose kids are being promised huge payouts when they go pro but for the time being aren't allowed even a part-time job for pocket money. (Meanwhile, is this the coach's car?)

If the financial game is rigged against those players, they might see two paths: play the unofficial game and get paid, or play by the rules for as long as they need to and watch the league, the coach, the institution and affiliated corporations profit off their labor and likenesses. Adults on all sides are clearly willing to exploit the players' desires to make the deals they need to keep winning at any cost. Meanwhile, Louisville freshman Brian Bowen, the star recruit widely believed to have been a target of the pay-for-play allegations in question, has been suspended from athletic activities. The NCAA treats its recruits and players like children who need to be sheltered when it suits the league's economic interests, and adults with full responsibility to say no to the temptations around them when it doesn't.

Why do we expect teenagers to take the high ground in situations when moral guidance from the very people who have told them what to do their entire lives appears to be in dismally short supply? This brings us to the real reason Pitino should have been fired two years ago, when explosive allegations came out that one of his assistant coaches hired sex workers to to strip for and engage in sex acts with students and recruits, some of whom were as young as 16.

As an undergraduate — not at the University of Louisville — I worked as a recruitment host for a year in exchange for a break on my dorm bill. My roommate and I housed high school seniors in our room overnight and gave them a taste of college life. As I recall we never so much as let anyone pass those girls a beer on our watch, let alone supplied them with sex workers. If your response is "well, that's different," ask yourself why you think that.

An NCAA investigation confirmed the allegations and levied sanctions. Pitino has weathered a multi-game suspension, but kept his job, while maintaining his ignorance of his employee's efforts to bribe other people's underaged sons with sexual favors. The community seemed determined, before this last week's news blew up, to try to get past the ugly episode and get back to winning. In a healthy environment, where such a brazen violation of norms would be considered truly aberrant, the head coach would have been forced to resign in disgrace or else be sacked. As the NCAA states in its rules, "An institution's head coach is presumed to be responsible for the actions of all institutional staff members who report, directly or indirectly, to the head coach." At the very least that investigation should have served as a wake-up call, a warning, and yet here the program is again. To be fingered in one sordid scandal may be regarded as a misfortune; to do it twice looks like carelessness bordering on hubris. Perceived invincibility must be a hell of a drug.

I'm no fan of the exploitative NCAA amateurism rules, and I believe they should be overhauled so that shoe companies can deal directly with players for sponsorships and some of the big money can be honestly earned by those who work for it. Yet these are the rules all college coaches sign on to uphold at — all evidence to the contrary aside — ostensible institutions of higher learning with higher ideals, we hope, than cash-raking on the line. That Pitino was allowed to keep his job after the recruitment sex parties scandal says volumes about the implicit values of the system under which his career has flourished. That the same system is now under serious investigation should come as no surprise.

Shares