When the subject is sexism and sexual harassment, everyone in Hollywood — even those considered to be Hollywood adjacent — has a story to tell.

Here’s one that involves a familiar sitcom actor. Years ago, at the height of his popularity, this man felt so cocksure about his place in the industry ecosystem that in front of a group of journalists holding recording devices he made lurid, sexually suggestive comments to a female reporter. When said reporter recounted her harassment to a female writer on his series, the woman refused to believe her.

There there’s the star known for being a sex addict and a serial groper, a man I interviewed many years ago in the presence of at least five publicity representatives. As a publicist and friend explained to me later, his reputation led them to take measures to keep the network out of trouble.

While I can assure you that there are people out there who know exactly to whom I’m referring, there’s no way that I’ll reveal their names in print. I am Hollywood adjacent-adjacent, too tiny to qualify as a small potato. Either of those people could sue me or the outlet I work for into oblivion or, at the very least, make it impossible for me to do my job.

Writing about television requires journalists to have certain level of access. Sometimes means enduring insults verbal and physical, the likes of which the public rarely if ever hears about. Except, that is, on the rare occasion that a whale like Harvey Weinstein is finally beached and flensed.

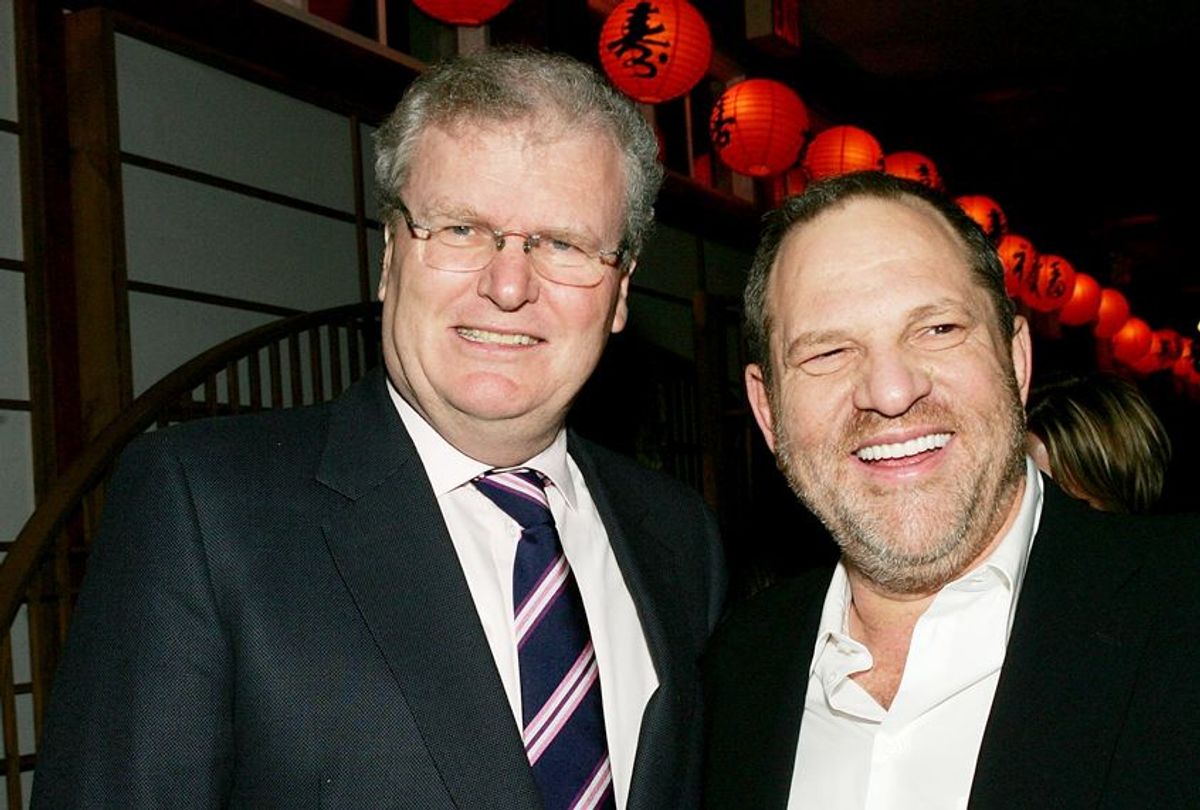

Therefore, you’ll have to forgive me if I greet the optimism expressed by the likes of former Sony CEO Howard Stringer with disbelief, if not complete disdain.

In an interview with The Hollywood Reporter the industry executive, who lent his two cents on the matter while appearing at the international television trade show event known as MIPCOM in Cannes, optimistically referred to the Weinstein scandal as “a watershed moment.”

“It's not 40 years ago when studio executives behaved very badly and the casting couch was quite evident,” he told the trade publication. “Even though there were strong women in Hollywood then, there was a sense that they couldn't beat the system. Now the women are organized and united and together will beat the system, whether the men want it or not.”

Oh, Howard. Oh, sir. What a lovely and very false soundbite.

Consider this nexus in time that we’ve reached. Weinstein, Bill O’Reilly, Roger Ailes and Bill Cosby have suffered recent tumbles from grace, with O’Reilly and Ailes receiving lucrative golden parachutes to soften their falls.

Others accused of sexual harassment and assault before the Weinstein fracas and in its wake, including Harry Knowles, Devin Faraci, Lars Von Trier, Hadrian Belove and Roy Price, must be thanking their lucky stars for the massive inky shadow Weinstein is casting. Influencers such as Matt Damon are stepping up and professing their ignorance; screenwriters such as Scott Rosenberg are coming out and nearly bragging that what we suspected to be true, truly is: That, in his words, “Everybody-f**king-knew.”

Women, though, we’re the ones coming forward in greater numbers. A-list actresses, producers, TV writers revealing what happened to them in public settings or behind the closed doors of work rooms with male colleagues.

Stringer means well, and I’m sure he figures the highest gift he can offer is hope. A man doesn’t survive at the helm of a major broadcast network for seven years without knowing the right way to spin things, and Stringer served as CBS’ president from 1988 to 1995.

But the law of averages guarantees that the man had at least a few rumor generators in his employ. And those men are as much part of a problem as the public figures, if not more. The sad truth is that the Hollywood system is set up in order to ensure that women as a whole will not beat the system because its structure has long favored men and will continue to do so for the foreseeable future.

Also notice that Stringer is leaving it up to women and our mythical ability to organize, unite and beat the system together. Rose McGowan's and Alyssa Milano’s social media campaigns certainly sell the illusion that such a thing is possible.

But the grim truth is that women will find it difficult, if not impossible, to beat the Hollywood system because men in power do not want them to. Worse, a number of those men incentivize some women to keep quiet or, as we saw with Donna Karan and Weinstein’s former counsel Lisa Bloom, work against their own interests. Playing oppressed parties off of each other is a winning strategy to maintain a grip on power.

But none of these men and women others like them can operate without the acquiescence and assistance of other people operating at far lower rungs on the ladder. People, I should add, who follow the examples set for them by those in higher profile places of power.

Such as: the influential media personality with whom I was forced to work at a previous place of employment. Said person dug up a photo from my Facebook page I did not give him permission to use and circulated it around the industry. When I protested this, he explained in an email that he thought the photo looked “kinky,” following this with a string of onomatopoeic words made to convey the image of him slurping and wiggling his tongue at me (Not that it should matter, but in the photo I was dressed in an evening gown for a wedding — not “kinky,” nor an image I’d use in a professional context).

I reported this to the man who was my boss at the time, and he laughed it off. The guy was a friend of his, he explained. He “likes to joke around” and therefore I should “have a sense of humor.” I was forced to work with this joker on an annual basis for several years, thereby reinforcing that I am smaller than small potatoes.

The screwed-up part is I had to actually read through the accounts submitted by Weinstein’s victims to realize that what happened to me was indeed, harassment. That my feelings of disempowerment were legitimate, something I was made to doubt because I was not publicly humiliated by a star live, in person, in front of my peers. And because I have a close friend who was subjected to worse by someone in the entertainment industry. Much worse.

This is why the discussion has turned from rolling waves of shock at the enormity of Weinstein’s crimes to the pervasiveness of sexual harassment and abuse throughout the industry, from producers offices to writer rooms to the crews. Sexism permeates every business but in Hollywood, where men hold a visible majority at just about every level, the practice is heightened.

What light there is in the clouds exists in data indicating that behind the scenes, women are faring better in TV than they do in film. This is according a report by to Dr. Martha M. Lauzen, executive director of the Center for the Study of Women in Television and Film at San Diego State University.

Nevertheless the road to gender parity with regard to the people who produce, direct and write television remains long. The Center’s most recent Boxed-In report, which has tracked women’s representation in prime-time television for the past 20 years, indicates that women still only account for 28 percent of executive producers, 33 percent of writers, and 17 percent of directors on television programs as of the 2016-17 season.

That’s still better than the data attached to 2016’s top 250 films, for which women comprised only 17 percent of executive producers, 13 percent of writers, and seven percent of directors.

Even so, that still means that the majority of executive producers, as well as directors employed by studios and majority of writers, are men. And they have a significant say in who gets hired, promoted, and whether harassers are accommodated or held accountable.

Misogyny infects every level of the business, from studio executives and stars all the way down to a press that assists in keeping all kinds of sicknesses a secret. We know this, just as we know that in some cases, as my colleague encountered, select women choose to aid and abet the perpetrator. Or, as Patton Oswalt observes:

This is ONE GUY. If you see one cockroach, it means there’s a thousand. http://t.co/elEPQ8bmdo

— Patton Oswalt (@pattonoswalt) October 16, 2017

Though pieces in The New York Times and The New Yorker and numerous stories that have followed those include accounts of Weinstein manipulating the media to impact or destroy the credibility of his victims, other accounts point out that many reporters have tried and failed to hold Weinstein accountable for years. What can the common reporter do against the razor-toothed machine of an industry invested in protecting predator? Indeed, how is any professional — the journalist, the TV writer, the actor, the crew member being subjected to harassment or witnessing it — how are they supposed to fight these larger battles when they’re not sufficiently protected in their own workplaces?

“It's hard to believe this isn't a sea change,” Stringer effused confidently from his top-of-the-mountain perch. But we’re all better off embracing the truth that it isn’t, otherwise we can fool ourselves into thinking we don’t need to keeping fighting for a better story.

Shares